Each week, we’re compiling the most relevant news stories from diverse sources online, connecting the latest environmental and energy economics research to global current events, real-time public discourse, and policy decisions. Here are some questions we’re asking and addressing with our research chops this week:

Banks are increasingly divesting from coal—but are they concerned with climate change, or just their bottom line?

JPMorgan—the world’s biggest financier of fossil fuel companies—released a new set of climate commitments this week. These include ending all existing loans to coal companies by 2024; no longer advising companies that generate over half their revenue from extracting coal; and committing $200 billion to projects that meet the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. The announcement comes after the leak of an internal report from JPMorgan economists, which “implicitly condemns the US bank’s own investment strategy” of financing fossil fuel companies. With this strategic shift, JPMorgan is following Goldman Sachs, which has announced stringent restrictions on new coal investments, and BlackRock, which no longer funds companies that make more than a quarter of their profits from coal. And while these banks are largely justifying divestment with environmental concerns, some analysts wonder whether these new principles reflect the decline of coal more than earnest efforts to mitigate climate change.

This week on the Resources Radio podcast, climate scientist Zeke Hausfather discusses the implications of coal’s downturn on global energy use, emissions, and climate models. After a rapid expansion of coal power in China in the early 2000s prompted a steep rise in emissions, coal is quickly being displaced by natural gas and is now trending well beneath its global peak. As the extent of this decline was largely unexpected, many preexisting, frequently cited climate models that predict future emissions still hinge on the assumption that coal power will expand, which means that some projections might be unrealistically catastrophic. “We can't necessarily preclude the possibility that the world will decide to burn all the remaining coal we have,” Hausfather says, “but it's much more of a worst-case scenario now than a likely outcome.” For more on why ambitious mitigation strategies are still necessary despite coal’s decline, listen to the podcast.

Related research and commentary:

With growing interest in hydrogen as a fossil fuel alternative, what are the options for expanding low-carbon hydrogen production?

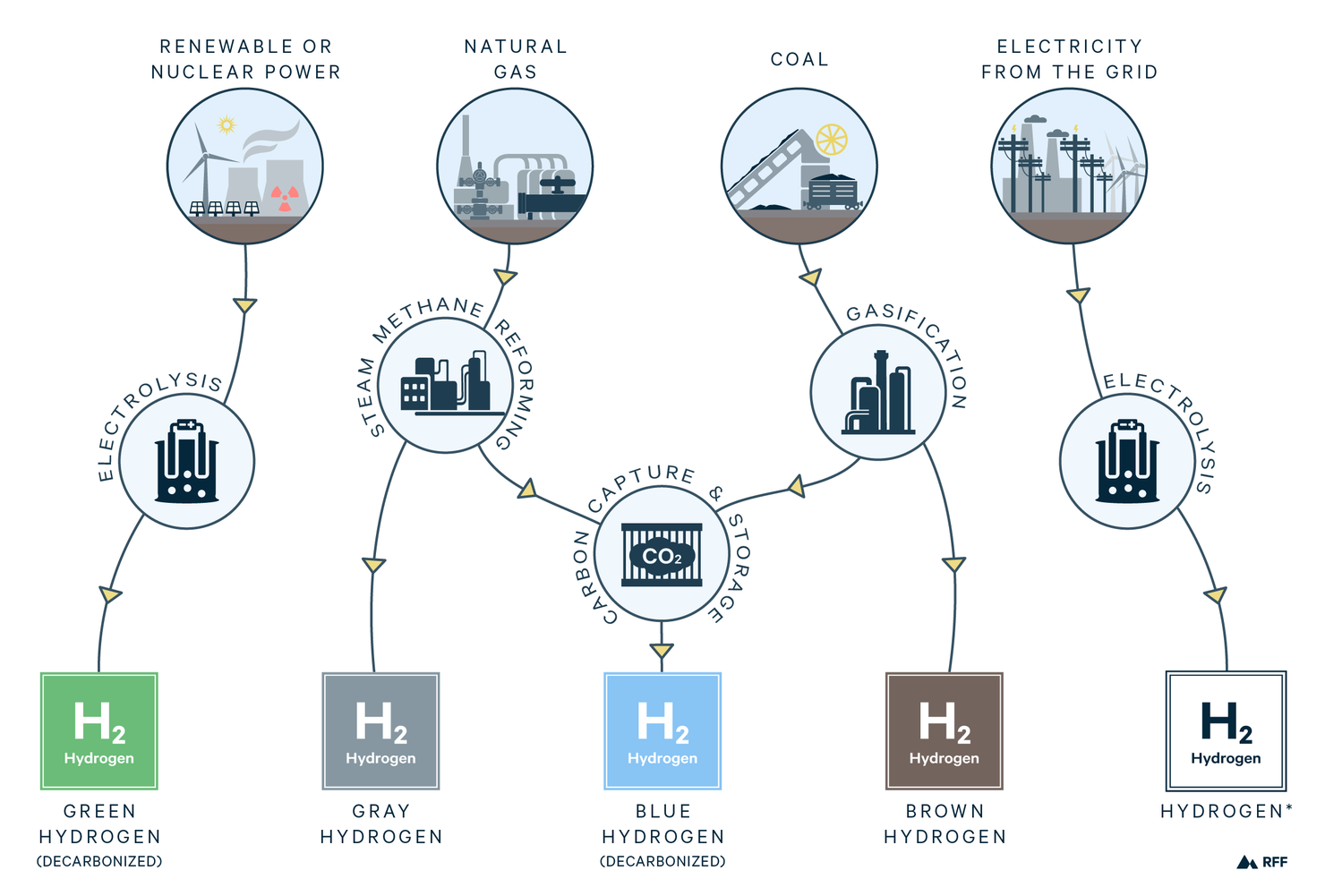

In the search for energy sources that could provide a cost-effective replacement for fossil fuels, investors and governments are increasingly optimistic about hydrogen. An alternative fuel that produces no CO2 when combusted, hydrogen has various uses in transportation, energy storage, building heating, and industrial processes. Last week, the UK government pledged £28 million to fund five hydrogen production projects, two of which will be “low-carbon hydrogen production plants” utilizing offshore wind power for hydrogen electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Meanwhile, the vice president of the European Investment Bank urged the European Union to set a target to drive down the costs of green hydrogen production, which could push natural gas out of the market and contribute to Europe’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. Investors are taking notice of this renewed interest, with hydrogen-linked stocks climbing to their highest levels in more than a decade.

In a new issue brief, RFF researchers Jay Bartlett and Alan Krupnick expound on the potential for low-carbon hydrogen in the United States, particularly in the context of tax credits for energy storage, which were proposed previously but ultimately not included in the final legislation. Bartlett and Krupnick assess the critical challenge of decarbonizing hydrogen production processes, as over 95 percent of hydrogen generation currently relies on carbon-intensive processes using coal and natural gas. However, hydrogen generated from electrolysis using clean electricity from renewables or nuclear power offers a low-carbon alternative. Although the proposals to incentivize energy storage stalled in Congress, expanding low-carbon hydrogen production and lowering costs can be possible with the right policy design. To learn more about the different types of hydrogen production, take a look at the #ChartOfTheWeek above and read the issue brief.

Related research and commentary:

In a complex and evolving energy landscape, what projects will the US Energy Secretary prioritize?

Testifying before the House Appropriations Energy and Water Subcommittee yesterday, Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette fielded questions about the recent, controversial 2021 budget request that impacts the Department of Energy (DOE): the Trump administration has proposed reducing the DOE’s spending by 8 percent, primarily by restricting funds for the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, cutting back on research, and eliminating a subagency tasked with developing advanced energy technologies. Offsetting these cuts, the proposed budget also allots increased funds for “safeguarding the nuclear weapons stockpile”—reflecting the expansive responsibilities of the DOE, which range from scientific research to energy conservation to natural security. In response to a question from Representative Derek Kilmer about proposed cuts, Brouilette replied, “I understand the optics of reducing the budget, but it’s very important that we look at the results … What is it that we’re producing with this money?”

Next week, RFF will host former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz for a far-reaching discussion as part of RFF’s ongoing Policy Leadership Series. Alongside RFF President and fellow DOE alum Richard G. Newell, Moniz will discuss the current landscape of energy policy, the importance of technological innovations for reducing emissions, and best practices learned from his nearly four years as head of the sprawling department. Moniz will also expand on his idea for a “Green Real Deal,” envisioned as a policy alternative to the Green New Deal that carries comparably ambitious aims for resolving contemporary climate challenges, but encourages participation from businesses, as well. To hear more of Moniz’s reflections on his long career in energy research and policy, RSVP for the event now.

Related research and commentary: