Twice a month, we’re compiling the most relevant news stories from diverse sources online, connecting the latest environmental and energy economics research to global current events, real-time public discourse, and policy decisions. Keep reading, and feel free to send us your feedback. Here are some questions we’re asking and addressing with our research chops this week:

The Inflation Reduction Act creates tax incentives that provide economic support for energy communities in the United States. What qualifies as an “energy community”?

Last week, the lone remaining coal plant in Oregon, near the city of Boardman, was demolished. The plant had provided jobs for about 125 workers in the region. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, the plant’s retirement qualifies Boardman as an “energy community,” a jurisdiction that has been especially affected by the energy sector. Boardman’s classification as an energy community means that developers that want to build solar energy farms, for example, will receive tax incentives if they choose Boardman as the site of development. Given how the Inflation Reduction Act defines an energy community, however, the legislation may not reach all the communities that need its provisions the most. In a new blog post, RFF scholars Daniel Raimi and Sophie Pesek apply available data to review the extent of the law’s reach. “Do these definitions in the [Inflation Reduction Act] target the energy communities that are likely to be hardest hit by a transition to a net-zero energy system?” ask Raimi and Pesek. “[T]he answer appears to be no.”

The Inflation Reduction Act and last year’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act contain provisions that spur the development of the hydrogen fuel industry in the United States. Who can take advantage of these incentives, and how can the US Department of Energy optimize the design of related programs?

Seven midwestern states have announced their entry into the Midwestern Hydrogen Coalition, which aims to create jobs and reduce carbon emissions by bolstering hydrogen fuels in the region. Other efforts by groups of states in the South and the West earlier this year seek to develop hydrogen hubs (geographically concentrated hydrogen networks) in their respective regions with federal funding from last year’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. Tension among groups that compete for federal funding, however, could hinder collaboration within such state coalitions in the hydrogen sector, say RFF scholars Yuqi Zhu and Alan Krupnick in a recent blog post. “One potential solution that could spur cooperation,” say Zhu and Krupnick, “would be to ask [hydrogen hub] proposers to develop a cooperative information-sharing plan as part of their initial proposal, recognizing that the plan wouldn’t go into effect until the final winners are known.”

How are US states pursuing decarbonization in the electricity sector?

A year ago last week, Governor J. B. Pritzker (D-IL) signed the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act into Illinois state law. The law sets a pathway for Illinois to achieve a carbon-free electricity grid by 2045, with complementary goals of 40 percent renewable energy generation by 2030 and 50 percent by 2040. More recently, Governor Gavin Newsom (D-CA) signed a series of climate bills into California law, including one bill that establishes as state policy the goal of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. To achieve their targets, however, states will need to overcome barriers involved in building up new electricity generation and connecting that electricity to the grid. In a new blog post, RFF Senior Research Analyst Maya Domeshek shares related insights from a workshop that RFF co-hosted. “Decarbonizing the electric grid,” says Domeshek, “will require the states to engage with institutions and regulators in the electricity sector, along with government entities at all levels.”

Expert Perspectives

In Focus: The Fiscal Impacts of California’s Wildfires

For the second video in our new In Focus series, RFF Fellow Penny Liao shares insights on how California wildfires have fiscal consequences for cities and local governments.

Virginia Governor Seeks to Remove State from Regional Carbon Emissions Market

Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin (R-VA) is considering pathways through which his administration could withdraw the state from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) by the end of 2023 without approval from the state legislature. RGGI is a coalition of northeastern states that caps carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector by creating a limited market for emissions allowances. The emissions cap declines over time, which incentivizes RGGI’s member states to reduce their use of fossil fuels.

The Youngkin administration has cited an increase in retail electricity rates for Virginians as the motivation to withdraw from RGGI. The rate increases have resulted from Virginia’s primary energy utility, Dominion Power, passing some costs associated with participation in RGGI along to customers. “If Virginia left RGGI, we’d likely see an increase in the cost of achieving the goals of the Virginia Clean Economy Act, which requires state utilities to eliminate their carbon emissions by 2050,” says Dallas Burtraw, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future. “Virginia would lose the gains from engaging in the emissions market and lose funding for energy-efficiency programs, too.”

Mapping the Pathways Toward Grid Decarbonization

A recently released report by RFF scholars Daniel Shawhan, Steven Witkin, and Cristoph Funke examines several methods of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the US power sector. “The power sector is the second-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States and accounts for one-quarter of total emissions,” they say. “Decarbonization of the power sector can play a leading role in cost-effective, economy-wide emissions reductions.”

How Are Gasoline Prices Determined?

In a new explainer, RFF Fellow Beia Spiller and collaborator Heather Stephens describe the factors that affect gasoline prices, how prices have changed over time, and how consumers react to changing prices. “By having a clear understanding of what affects gasoline prices and how households respond,” they say, “we can begin to identify policies that will be most effective in reducing the impacts high prices have on households.”

Unveiling Hidden Energy Poverty in the United States

Destenie Nock joined the Resources Radio podcast last week to discuss the extent of energy poverty in the United States. “In 2020, [the US Energy Information Administration] reported that 27 percent of US households had difficulty meeting their energy needs,” says Nock. “We believe that there are more homes that are not self-reporting these indicators because one thing that we know about people who experience poverty is that nobody actually wants to admit it.”

Vulnerability to the Energy Transition in US Fossil Fuel Communities

A new journal article coauthored by RFF Fellow Daniel Raimi ranks and maps the counties in the United States that are most likely to be affected by a transition away from fossil fuels. “The energy transition toward lower-carbon energy sources will inevitably result in socioeconomic impacts on certain communities,” say Raimi and his coauthors. “Counties in Appalachia, Texas and the Gulf Coast region, and the Intermountain West are likely to experience the most significant impacts.”

Tracking the Price of Carbon

Carbon pricing is a climate policy approach that charges emitters for the carbon dioxide they emit. In a recent journal article, RFF Postdoctoral Fellow Geoffroy Dolphin and former Research Analyst Qinrui Xiahou introduce a database that tracks the implementation of carbon prices across the globe. The database is “a valuable tool to track the development of carbon pricing mechanisms,” Dolphin and Xiahou say, providing “enough data to analyze their impact in a broad range of social, technological, and sectoral contexts.”

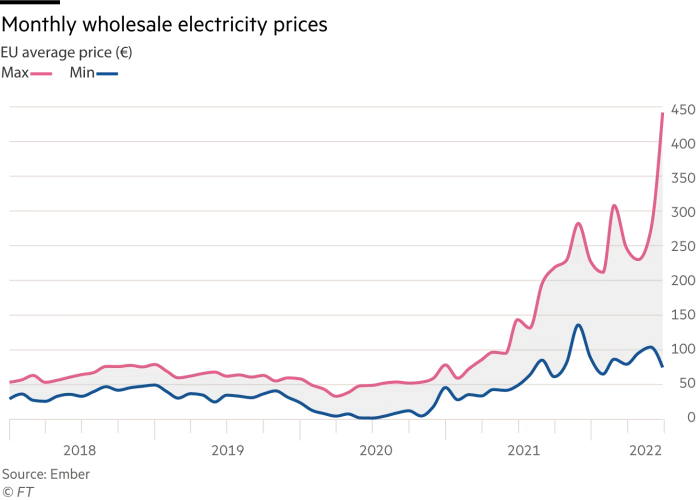

#ChartOfTheWeek

Russia has cut off its deliveries of natural gas to much of the European Union, as a response to EU sanctions over the war in Ukraine. Because EU market rules dictate that the most expensive provider of electricity will set the wholesale price for all electricity suppliers, the natural gas stoppage that caused a spike in natural gas prices throughout Europe increased electricity prices, too. The EU rules also mean that, even if some renewable energy sources generate electricity more cheaply than natural gas plants, those renewables aren't likely to decrease the wholesale price of electricity.