Each week, we’re compiling the most relevant news stories from diverse sources online, connecting the latest environmental and energy economics research to global current events, real-time public discourse, and policy decisions. Here are some questions we’re asking and addressing with our research chops this week:

As more cities impose restrictions on private vehicles because of traffic and pollution concerns, how will they regulate ridesharing?

Last week, San Francisco officially banned private cars, including those used for ridesharing apps like Uber and Lyft, from driving on Market Street. The city is following the lead of New York City, which banned private vehicles across much of Times Square, and Amsterdam, which hopes to ban all gas and diesel cars by 2030. Municipal restrictions on private vehicles are often designed to bolster public transit; after New York City banned cars across much of its crowded 14th Street earlier this year, bus travel times declined 38 percent, and weekday ridership rose 17 percent. Public transit along Market Street, which hosts 75,000 transit riders a day and as many as 200 buses an hour, stands to benefit. And while the purpose of these restrictions might be to encourage other modes of travel, the environmental benefits of reducing traffic congestion and incentivizing public transit are potentially substantial, too.

This week, RFF Fellow Benjamin Leard and Peking University’s Jianwei Xing released a new working paper assessing the environmental impacts of ridesharing. Investigating which types of transit people would have used if apps like Uber and Lyft had been unavailable, Leard and Xing find that ridesharing tends to replace private car or taxi trips, and thus has only slightly increased total vehicle miles traveled and greenhouse gas emissions. But their evidence also suggests that the effects of ridesharing depend significantly on the availability of public transit. Consequently, a city with a robust public transit system like San Francisco might have more reason to rein in private vehicles: according to Leard and Xing, greenhouse gas emissions have increased more in San Francisco since the introduction of ridesharing than in any other major city. For more context on why they contend that ridesharing regulations should be done “at a local, city-by-city level,” read their working paper and our accompanying blog post.

Related research and commentary:

Miami is one of the cities most vulnerable to the effects of climate change—does that mean the city hosted its last Super Bowl this year?

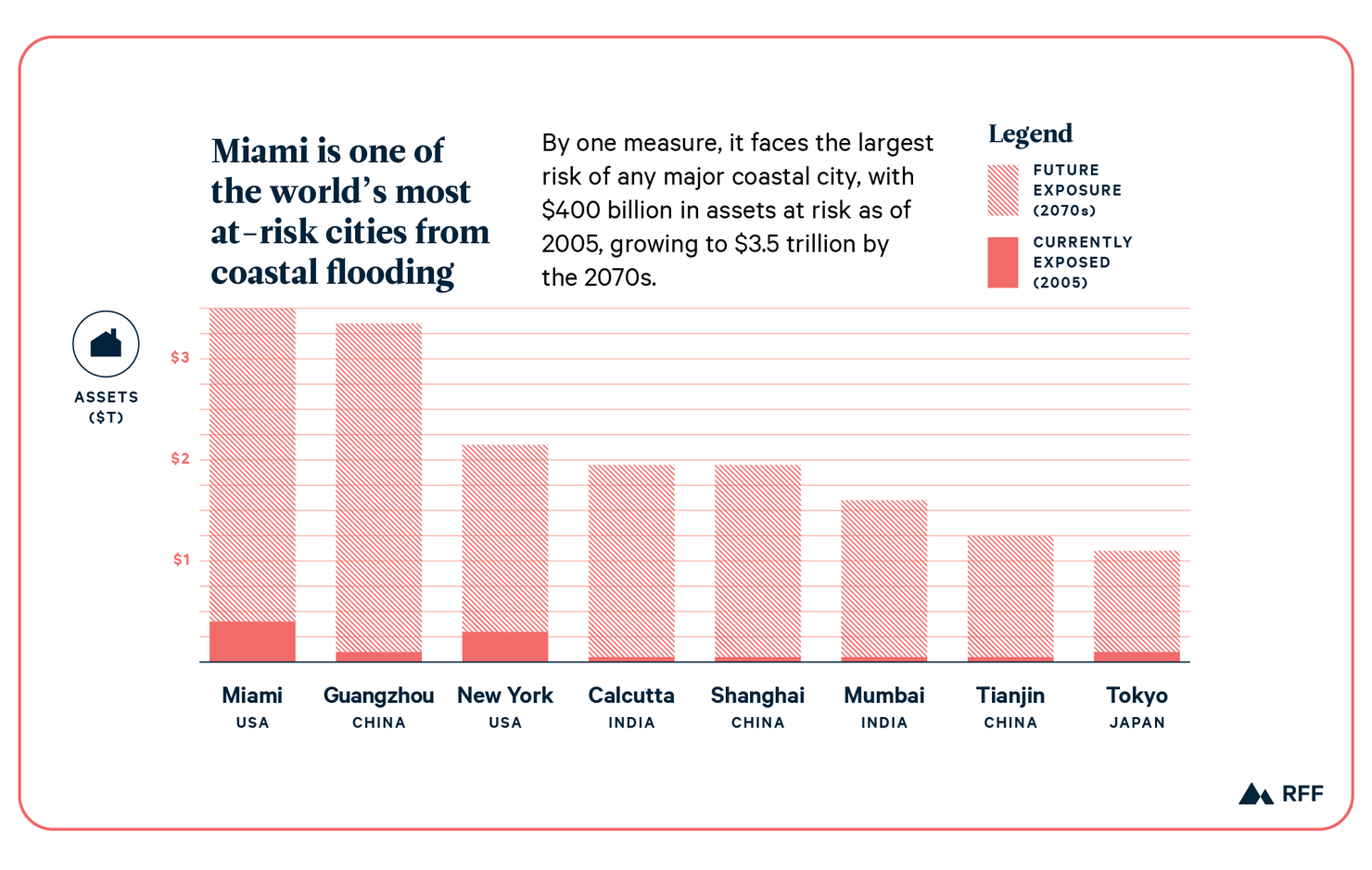

Last weekend’s game was the 11th Super Bowl held in Miami—meaning the city has hosted more Super Bowls than any other. But as one of the most at-risk cities in the world in terms of potential damages from climate impacts such as sea level rise, flooding, and storms, some worry that Miami might not be able to continue hosting major events like the Super Bowl. A new RFF report, the Florida Climate Outlook, has made headlines with one of its key findings: Miami is facing major threats because of climate change, and things could get more dire within the next ten to twenty years.

Miami has over $400 billion in assets vulnerable to coastal flooding and storms—the largest amount of any major city in the world. And the future looks hazardous for football: with a dramatic increase in the number of days per year predicted to hit temperatures above 95 degrees—from roughly seven days per year in 1981–2010, to potentially 22–28 days annually—could make the climate less hospitable to both athletes and fans in Miami’s open-air stadium. The likelihood of more frequent and more powerful storms could also seriously damage infrastructure and tourist attractions like Miami Beach, potentially deterring organizers from selecting Miami as a host city for future events. But another essential takeaway from the report is that these impacts are not inevitable. With strategic climate policy and concerted efforts toward resilience, Miami can reduce the risks it faces and potentially host many more Super Bowls.

Related research and commentary:

Could an EU carbon tariff help member countries reach their ambitious climate goals, or would a tariff prompt a trade war with the United States?

The European Union is considering a “carbon tariff,” a potentially provocative consideration just prior to scheduled trade negotiations with the United States. Some European leaders have expressed concerns that the ambitious approach to climate change favored by the European Union, which notably includes an emissions trading system, might burden European companies relative to competitors in countries without their own carbon price. Still, a carbon border adjustment mechanism is seen by others as a necessary step for leveling the playing field. A border adjustment would also bolster climate goals in the European Union, as a carbon tariff could incentivize affected countries to pursue more ambitious climate policies. Still, the actual design of any proposed tariff is unclear, and many European leaders fear that a mechanism like a carbon tariff would make a trade war inevitable with the United States, given the Trump administration’s decision to exit the Paris Agreement.

This week on Resources Radio, Amy Harder—energy and climate change reporter at Axios—discussed major developing stories that she’ll be tracking in the coming year. One of those is a possible trade dispute between the European Union and United States and the potential for a carbon tariff, which could escalate disputes over climate policy. And Harder is not alone in this prediction: former Secretary of State John Kerry, speaking broadly about the potential for a carbon tariff in other countries, as well, attested last year: “It’s not whether it’s going to happen—it’s going to happen.” In considering whether a carbon tariff could encourage the United States to overhaul its climate agenda, Harder says, “In the current political environment ... I think it’s more likely that the Trump administration will respond with unrelated tariffs—for example, on wine, which he’s already doing.” For more insights from a dogged reporter, listen to the podcast episode with guest Amy Harder.

Related research and commentary: