Each week, we’re compiling the most relevant news stories from diverse sources online, connecting the latest environmental and energy economics research to global current events, real-time public discourse, and policy decisions. Here are some questions we’re asking and addressing with our research chops this week:

What can Florida lawmakers do to prepare communities for the imminent effects of climate change?

The years of inaction on climate change from Florida lawmakers might be over. Politicians from both parties are increasingly considering solutions that prioritize readiness for the imminent threat that climate change poses to Florida communities, including impacts such as rising seas and more powerful storms. One actionable step taken last week: the Florida House Agriculture & Natural Resources Subcommittee unanimously voted to advance legislation that would establish a statewide Office of Resiliency and sea level rise task force. This builds upon other steps that Republican Governor Ron DeSantis has taken to address the impacts of climate change and water pollution, such as appointing the state’s first ever “climate change czar” and committing to spend billions to revitalize the Everglades. Still, the state’s mitigation efforts notably avoid setting emissions reduction targets.

In an op-ed published this week in the Tampa Bay Times, RFF researchers Daniel Raimi, Amelia Keyes, and Cora Kingdon explore the critical role that climate policy—particularly carbon pricing policy—could play in protecting Florida from the devastating consequences of business-as-usual emissions scenarios. The op-ed summarizes findings from the Florida Climate Outlook, a new, comprehensive report that assesses the physical and economic impacts of climate change on Florida within the next twenty years, and also calculates the financial impacts that national climate policies would have on Florida households. Raimi, Keyes, and Kingdon find that carbon pricing policies, which include dividend payments (four of the eight currently proposed policies they analyzed), would “more than offset the increases in energy prices for low- and moderate-income Florida households, leaving them better off.” For more insights on how Florida can prepare for the substantial risks posed by climate change, read the report here.

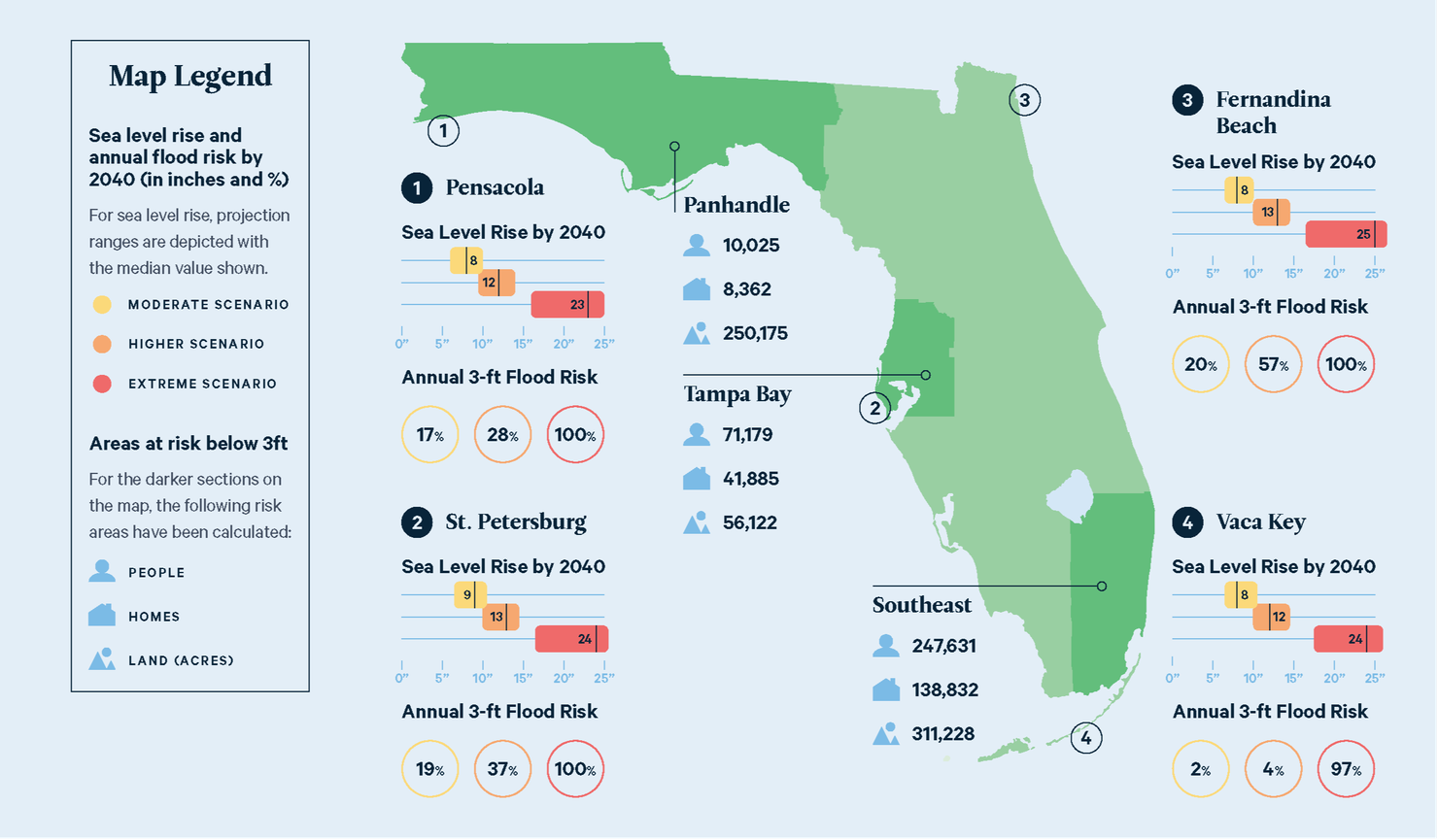

This #ChartOfTheWeek, taken from the Florida Climate Outlook, shows the state’s near-future sea level rise and annual flood risk. Rising seas threaten the 490,000 Floridians who live on land less than three feet above the high-water mark and imperil coastal properties worth an estimated $145 billion

Related research and commentary:

With changes pending for Oregon’s carbon pricing proposal, will the bill still reduce emissions in the state?

This Monday, Oregon lawmakers will convene for a new legislative session, and Governor Kate Brown’s top priority is passing cap-and-trade legislation. The viability of the current proposal is in question: a similar bill failed last year, amid concerns from lawmakers that carbon pricing would create an undue burden on businesses and rural areas. In response to these objections, the updated legislation would phase in carbon pricing for transportation fuels, starting with Portland in 2022 and expanding to smaller metro areas in 2025, but rural areas would not be affected unless they opted in. The bill would also change the point of regulation for natural gas consumption to upstream suppliers, thereby reducing the number of companies regulated directly for emissions from industrial processes from 30 to 11. Responding to the prevalent concern that carbon pricing would hamstring Oregon’s economy, Brown says, “I am committed to crafting climate policy that protects our environment and also grows our economy … we can do both.”

As the Oregon legislature prepares for a heated debate, RFF Senior Fellow Dallas Burtraw has contributed an issue brief describing key changes between this new carbon pricing plan and the one from last year. Burtraw argues that “the modifications … will not affect near-term emissions outcomes in the state, while addressing important concerns of some rural communities and compliance entities.” He also points out that the current proposal aligns approximately well with guidelines from the Western Climate Initiative, which administers the carbon trading market between California and Quebec, thus opening up future opportunities for linking the carbon markets. In contrast to some claims that carbon pricing would be economically burdensome, Burtraw predicts that “there should be virtually zero disruptions in employment” and eventually more opportunities for clean energy jobs. For insights on the potential consequences of this groundbreaking bill, read the full issue brief, “A New Approach in Oregon’s Greenhouse Gas Initiative.”

Related research and commentary:

As investors evaluate damages from last year’s fires, how do they measure the true cost of climate change?

A recent op-ed in the Guardian asks: “[F]rom insurance to tourism to ruined local economies, the numbers guys are starting to [consider the] question: what is the cost of climate inaction?” Recent extreme weather events raise the stakes. The long-term costs of Australia’s wildfires—which have ravaged an area almost the size of England, destroyed thousands of homes, and threatened to “cut up to half a percentage point off GDP growth”—are still being calculated. Similarly, last year’s wildfires in California caused up to $80 billion in damages and plunged PG&E into bankruptcy. Governments and financial institutions are responding: the influential European Central Bank, for instance, is considering the potentially insurmountable consequences of climate inaction. Some fear that these efforts do not go far enough: many Australians have been frustrated by a perceived lack of urgency on the part of pension funds and asset managers, many of which retain investments in fossil fuel companies.

Even with policymakers and investors approaching climate change as an economic problem, the future costs of climate change are hard to project. The related uncertainties make decisive emissions targets or investments in fossil fuel companies especially challenging. To quantify some of the unknowns, many researchers are using discounting to estimate a social cost of carbon. The nuances of both concepts are elaborated in RFF explainers—a series of publications that simplify nuanced environmental economics topics. In “Discounting 101,” RFF Postdoctoral Fellow Brian Prest analyzes how discounting, which involves converting a value received in the future to an equivalent value in the present day, “allows policymakers to measure the present value of the long-term benefits that come from reducing [emissions].” In “Social Cost of Carbon 101,” RFF Fellow Kevin Rennert and Research Assistant Cora Kingdon explain how a social cost of carbon—which uses discounting to estimate, in dollars, the damage of emitting one ton of greenhouse gases—can make the consequences of climate change more tangible.

Related research and commentary:

- Explainer: Discounting 101

- Explainer: Social Cost of Carbon 101

- Podcast: Pricing Climate Risk in the Markets, with Robert Litterman