Each week, we’re compiling the most relevant news stories from diverse sources online, connecting the latest environmental and energy economics research to global current events, real-time public discourse, and policy decisions. Here are some questions we’re asking and addressing with our research chops this week:

Can history-making prizes incentivize innovations effectively, or do better strategies exist for spurring technological progress?

Tesla CEO Elon Musk and the XPRIZE Foundation will offer the largest incentive prize in history to winners of a carbon capture innovation contest. The winning team, expected to be announced on Earth Day in 2025, will receive $50 million, while tens of millions more will be distributed among various runner-up teams. A growing group of researchers and policymakers have acknowledged the need for carbon capture to curb emissions and slow global temperature increases: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recommends removing 670 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere this century, while President Joe Biden has called for significantly more funds for carbon capture research and development in his American Jobs Plan. Despite growing interest, carbon capture equipment, energy, and transportation costs remain prohibitively high, and only a handful of large-scale carbon capture facilities currently exist in the United States. While technological advances likely will be essential for reducing the costs of decarbonization, questions remain over whether Musk’s contest will be a boon for carbon capture—or a flashy distraction.

On a new episode of the Resources Radio podcast, Bowdoin Economics Professor Zorina Khan discusses the potential of the XPRIZE contest and explores why attention-grabbing incentive prizes rarely produce scalable innovations. Reviewing her own research into such contests, Khan concludes that market-based systems—and the US patent system in particular—have historically proven more successful at spurring technological progress. That’s because contests often misallocate resources, reward innovations that will not be viable in the market, and obscure the process by which a winner is chosen. While Musk’s contest is helpfully drawing attention to the issue of climate change and the potential for carbon capture, Khan contends that policy reforms to drive markets toward emissions reductions are more essential than efforts to develop any one innovation. “All of my research shows that inventive activity responds to market demand,” Khan says. “Once we have markets like these in place, any necessary technological innovations will, I have no doubt, be found.”

Related research and commentary:

Are airlines ready to reduce the environmental impact of airplane travel?

Political and corporate interest in hydrogen-powered planes is growing—but major technological developments are needed before hydrogen can meaningfully reduce emissions from air travel. Two aerospace companies that are exploring hydrogen’s potential made major progress last year: Airbus unveiled three hydrogen-powered commercial airline prototypes, with the goal of deploying them by 2035, while hydrogen start-up ZeroAvia raised tens of millions of dollars from British Airways, Amazon, and the UK government. But significant challenges remain before hydrogen-powered planes can become viable: liquid hydrogen is considerably more expensive than jet fuel, and its lower energy density means a flight of the same length on a hydrogen-powered plane requires a heavier storage tank. Plus, while many analysts expect “green” hydrogen to become less expensive in the coming years, most hydrogen today is produced from natural gas or coal. So, although hydrogen could be a long-term decarbonization strategy, many airlines have prioritized reducing costs from other sustainable aviation fuels in the short term.

At an RFF Policy Leadership Series event this week, RFF President and CEO Richard G. Newell and United Airlines CEO Scott Kirby discussed United’s net-zero goals and challenges ahead for reducing emissions from the difficult-to-decarbonize transportation sector. Kirby expanded on his skepticism about forest offset schemes, on which many other airlines rely to reduce their emissions on paper, even if the success of these programs can be hard to measure in practice. Instead, Kirby sees carbon sequestration and direct air capture as opportunities for reducing the airline industry’s carbon footprint, and he suggests that federal policies—such as a price on carbon—are necessary to incentivize action by private companies. Sustainable aviation fuels also are a priority for United Airlines, and while costs remain a short-term hurdle, Kirby sees long-term potential for cleaner fuels. “We’re still in the investment stage, particularly for sustainable fuels,” Kirby said. “Once you start to get these technologies commercialized, then that can grow rapidly.”

Related research and commentary:

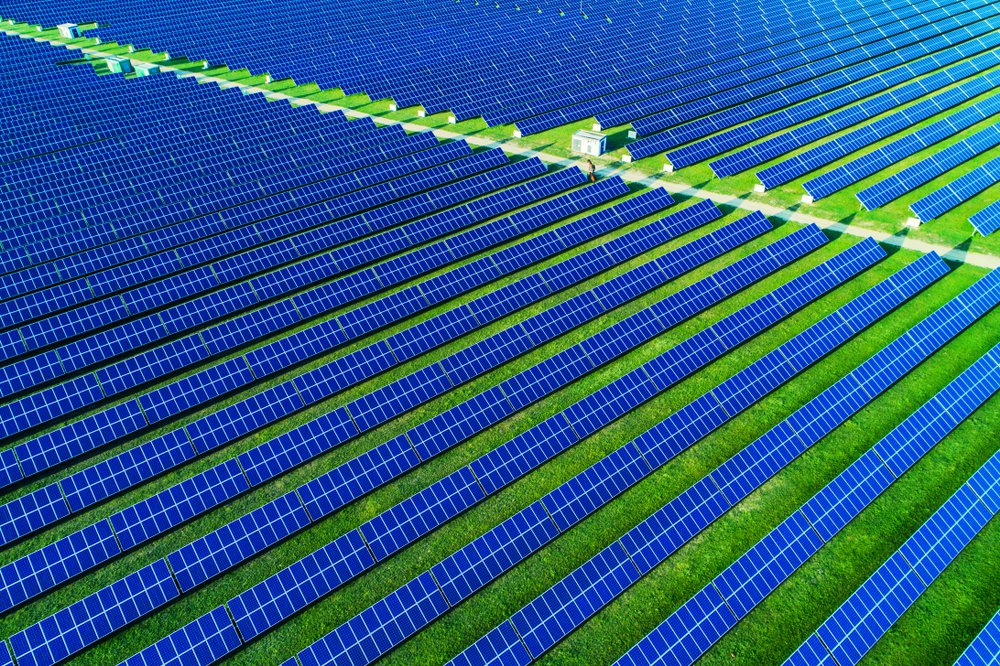

The permitting process for infrastructure projects is essential for minimizing environmental damages—but it can be lengthy. Can reforms to the process make it easier for clean energy projects to come online?

President Joe Biden’s pledge to rapidly build out clean energy infrastructure could be complicated by the administration’s simultaneous commitment to reassess environmental permitting rules. Former President Donald Trump revamped permitting in a bid to streamline the environmental review process for major infrastructure projects; now, the Biden administration is pledging to review Trump’s reforms with the goal of more robustly considering public input, environmental justice, and climate impacts. But the permitting process under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is notoriously arduous already, and clean energy and business groups fear expensive delays if the process becomes more complex. Council on Environmental Quality Chair Brenda Mallory, who is leading the administration’s review of environmental permitting, has made clear that the review process should facilitate “aggressive and high-charging deployment of renewable energies,” while others in the administration are hoping to speed permitting for transmission lines. But large projects still confront potentially long approval processes at a time when clean energy will be essential to meet increasingly ambitious US climate goals.

In a new working paper, RFF Visiting Fellow Arthur G. Fraas and coauthors examine how real-world solar projects have navigated the complex federal review process. The scholars investigate a sample of utility-scale projects that required a more rigorous review under NEPA, finding that the review process alone tends to take one to two years for projects that require an environmental impact statement. The approval process is especially complicated, too, for projects that must secure permits from multiple federal agencies. To expedite the process in the future, the scholars recommend proactively identifying land where such projects likely will impose minimal environmental impacts and developing renewable energy resources on Superfund and brownfield sites, which are unlikely to be further damaged by new construction. “The review processes in place for solar projects are important for protecting environmental and cultural resources, but they nevertheless can be implemented more expeditiously,” Fraas writes in an accompanying blog post.

Related research and commentary: