Prices soared in the market that pays electricity generators to be available to meet future demand in the PJM Interconnection, prompting policymakers, regulators, and researchers to debate the potential causes of increasing prices, along with solutions.

This summer, you may have seen some buzz around the PJM Interconnection, the regional transmission organization that manages the electric grid in 13 states in the Midwestern and eastern United States, along with Washington, DC. PJM held a routine capacity market auction, during which electricity generators promise to be electricity suppliers in a future year in exchange for payments from the system operator (PJM, in this case). The goal of the capacity auction is to procure enough commitments from generators to deliver electricity to meet anticipated levels of demand, plus some extra margin to cover uncertainties. Generators that offer this capacity service at the lowest prices are picked first, and the system operator accepts increasingly larger bids until the amount of future electricity promised equals the system needs. Prices soared in the capacity market auction in July, which covered the 2025/2026 delivery year, leading to a total capacity cost of $14.7 billion for the PJM region. This cost is up from $2.2 billion in last year’s auction.

This increase prompted concerns over the cost of electricity and how reliably PJM can meet future electricity demand. So, what exactly is driving these high prices? What do the high prices tell us about the future for capacity markets in PJM and other regional electric grids? And what policy solutions may offer relief from high consumer costs?

Power Plant Retirements, Growth in Demand, and a Long Wait to Connect New Electricity Generation to the Grid

To some extent, the high prices boil down to straightforward market dynamics: electricity demand is forecast to increase as the electrification of the economy continues and data centers multiply, while power plants retire as they get older and less efficient. The unprecedented high prices in the capacity market are sending the clear signal that such prices were designed to send: more energy suppliers are needed, and these suppliers will get paid handsomely.

Part of the problem is that potential electricity suppliers may be struggling to respond quickly enough to these price signals. Over 200 gigawatts of potential capacity are waiting in the line to be connected to the electric grid, known as the interconnection queue. Even if only a fraction of that capacity represents projects that actually will be built, those projects in the queue still represent new generators that could compete in the capacity market and contribute to lower prices in the future, if these generators are approved to connect to the grid.

Measuring Reliability and Defining Demand for Capacity

The high capacity prices may reflect adjustments to rules that have changed how generators are valued in capacity market auctions. PJM pays generators for promising to be available when needed, but just because a power plant can produce 100 megawatts of electricity on its best day doesn’t mean the power plant will generate that much electricity on an average day or when the electric grid is stressed (e.g., by high electricity demand during a heat wave).

A process called accreditation adjusts the value of capacity that is offered by generators, depending on the characteristics of the generator. For instance, a megawatt of capacity from a solar generator is less likely to be available when PJM calls than a megawatt from a nuclear power plant. Accreditation ensures that each generator gets compensated based on the predicted contribution of that generator to the reliability of the electric grid to meet demand.

PJM has employed accreditation in previous auctions, but in 2024, the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved a methodology called “marginal accreditation” that PJM had proposed. The recent capacity market auction was the first in which PJM deployed that accreditation scheme, which compensates generators based on the incremental reliability they contribute to the grid, after considering the other energy resources available and correlated availability of electricity across those resources. (Our report about ensuring sufficient electricity supply provides more details on the shift from average to marginal accreditation.)

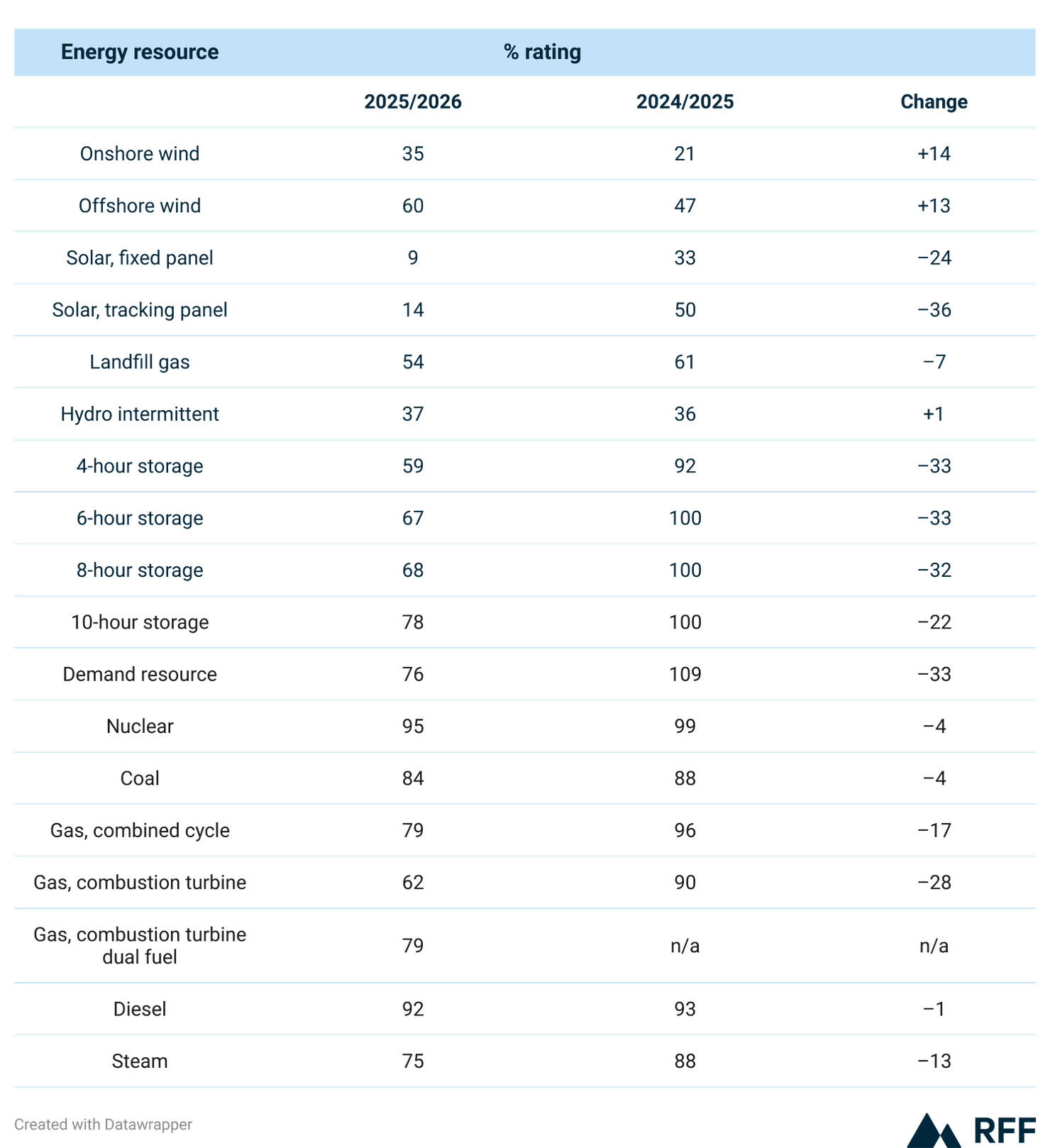

For many types of electricity sources, including solar energy and natural gas–fired power plants, the new marginal-accreditation methodology reduces the percentage of total installed capacity that is counted toward the reliability needs of the electric grid, compared to the previous accreditation scheme (Table 1). The result is that more installed capacity (i.e., the most electricity that a generator can produce) is needed to achieve the same amount of accredited capacity.

Table 1. Changes in the Accreditation Rating of Various Energy Resources

Source: PJM. Notes: These accreditation ratings are applicable for the regional transmission organization PJM Interconnection. The ranges of years 2025/2026 and 2024/2025 are delivery years at PJM.

The updated accreditation methodology comes with upsides. The methodology likely will increase the accuracy of PJM’s estimated capacity and provide clearer signals for which type of electricity suppliers add the most value to the system. Many observers thought that this improved accuracy could allow reductions in excess capacity that PJM procures as a buffer (called the reserve margin).

However, at the same time as PJM was making these adjustments, several other risk factors were changing. Earlier this year, PJM factored into calculations for its target reserve margin new estimates of the risk of power outages that are associated with an increase in both electricity demand and extreme weather events. Both factors led to an increase in the target reserve margin, so even more capacity would need to be procured to meet PJM’s threshold for reliability. Compared to estimates from 2022, the target reserve margin increased by nearly 3 percent. This higher reserve margin is compounded by the forecasted increase in peak demand for electricity that already was increasing the need for capacity.

The new accreditation methodology, more generator retirements, increased peak demand, and higher reserve margin had a predictable impact: the demand for capacity increased, while the supply of accredited capacity decreased. Still, the rule changes were not necessarily a bad idea, despite the resulting higher capacity prices. Recent events during which PJM could not meet demand for electricity, such as Winter Storm Elliott, demonstrated that the capacity market may not have been successful in accounting for correlated power outages during extreme weather events. To meet reliability standards, PJM may need to pay generators more to ensure that sufficient electricity is available when needed.

Renewables: Bidding Big or Sitting on the Bench?

Another factor that potentially contributes to high capacity prices is the uncertainty around the participation of variable energy resources, such as wind and solar. Some generators are not required to participate in the capacity market, and for many generators, participation may not be worthwhile. The capacity market offers some stable revenue, but generators are struck with costly penalties if they don’t show up when needed. For variable energy resources that rely on weather conditions (which are outside of anyone’s control), bidding in the capacity market can be a risky decision. Generators that use variable energy resources may choose to bid higher prices, given that they may face penalties down the line, or they may opt out of the capacity market altogether, which leaves fewer suppliers bidding in the capacity market and increases prices.

As the number of low-cost renewable electricity generators increases, the amount of revenue that generators expect to earn in day-ahead and real-time markets for electricity also may be impacted. With lots of wind and solar on the electric grid, the wholesale price at which generators are able to sell electricity is more likely to be at or near zero during some hours of the day. This possibility may result in generators of all types leaning more heavily on revenue from capacity markets to cover the fixed costs of operation, which can lead to higher prices in capacity markets.

The impact of these different market dynamics on overall electricity prices for consumers is difficult to estimate. The capacity market report from PJM for the recent auction did not provide detailed information on the bids and offers from generators in the PJM coverage area, but a report from an independent monitor of markets in PJM estimates that resources opting out of the capacity market auction drove up costs by as much as 39.3 percent.

Existing and Potential Solutions

Ultimately, capacity market prices are sending an important signal in the market: More generation needs to be built. Policymakers are looking to ensure that demand and supply can appropriately respond in order to reduce capacity prices. Several policies that could help reduce capacity prices in future auctions already are being implemented or considered.

Federal Regulations on the Books

In 2023, FERC issued Order 2023, which directed electric-grid operators such as PJM to improve and streamline the processes through which new generators connect to the grid. The deadline to comply with the regulation was in April 2024, so the entry of new generators to the grid may accelerate as the reforms are adopted this year. Research has suggested that reforms to the processes for adding generators can accelerate new entries, which could increase competition in capacity markets (and thereby reduce prices).

In 2024, FERC issued Order 1920, which set new rules for regional transmission planning and allocating the costs of building new transmission among beneficiaries. This reform is important, because insufficient transmission within a region can create prohibitive costs for new generators to connect to the grid. Regional transmission plans that consider reliability and the potential addition of generators can prepare the grid for connecting new generators and increase competition in capacity markets. Furthermore, increasing interregional transmission can reduce the need for electricity in specified zones by connecting a diversity of generators across zones.

Policy Considerations on the Horizon

Permitting Reform: Even when projects finally advance through the interconnection queue, hurdles and delays that are associated with permitting can prevent generators from becoming operational. While efforts to address federal permitting hurdles are ongoing, state and local rules on siting and permitting also present significant barriers and are harder to address comprehensively. An ongoing project at Resources for the Future (RFF) about obstacles to energy infrastructure aims to illuminate and quantify the consequences of some of these restrictions.

Demand-Side Activation: While PJM allows large sources of demand and aggregators of demand to bid in the capacity market, increasing the opportunities for demand to respond to high capacity and electricity prices has great potential to increase the affordability of electricity, particularly as variable energy resources are added to the grid. As electricity demand continues to increase, opportunities to manage demand also will increase, as will the costs that are associated with failing to enable consumers to adjust their electricity use.

Market Designs for the Future: PJM recently updated its capacity market rules in hopes of better integrating the contributions of variable energy resources and changes in demand and supply from season to season. But many economists have been thinking about more dramatic changes in market design that could help send price signals to power providers earlier and more clearly. A recent RFF report goes into detail on ideas for such designs and how these proposals could help ensure sufficient electricity supply on the grid. However, while some of these ideas may help clarify price signals, the designs may not actually reduce the cost of ensuring a balance of supply and demand.

The Debate Rages On

Several stakeholders came forward with ideas and proposals to address the price shock in the PJM capacity market in the weeks that followed the auction. Clean energy advocates have pushed for fast-tracking new generation through the interconnection queue and for generators that are near retirement and that have special reliability contracts to offer capacity services. The independent market monitor for PJM has made several recommendations, including requiring intermittent generators (e.g., wind and solar) to make offers in the capacity market and further adjusting the method by which resources are accredited. Some utilities owned by investors have even claimed that they should, through reregulation, take over from PJM the process of securing new capacity. Reregulation would move responsibility for providing incentives for investment in new generation from the competitive market to utilities that own both generation and power lines, get a fixed rate of return on their investment, and operate as regulated monopolies. While reregulation is unlikely, these historically high prices are forcing policymakers and regulators to consider what mix of solutions potentially could reduce prices in future capacity market auctions while preserving the role of the capacity market: to signal the need for new investments.