Global oil markets are, to put it mildly, on the skids. After several weeks of steady declines spurred by fears of reduced oil demand due to COVID-19, the bottom of the barrel fell out on Monday after the OPEC+ production alliance failed to reach an agreement on production cuts that could support global prices. What’s more, Saudi Arabia and Russia—the two most important players in OPEC+—subsequently announced plans to ramp up production dramatically.

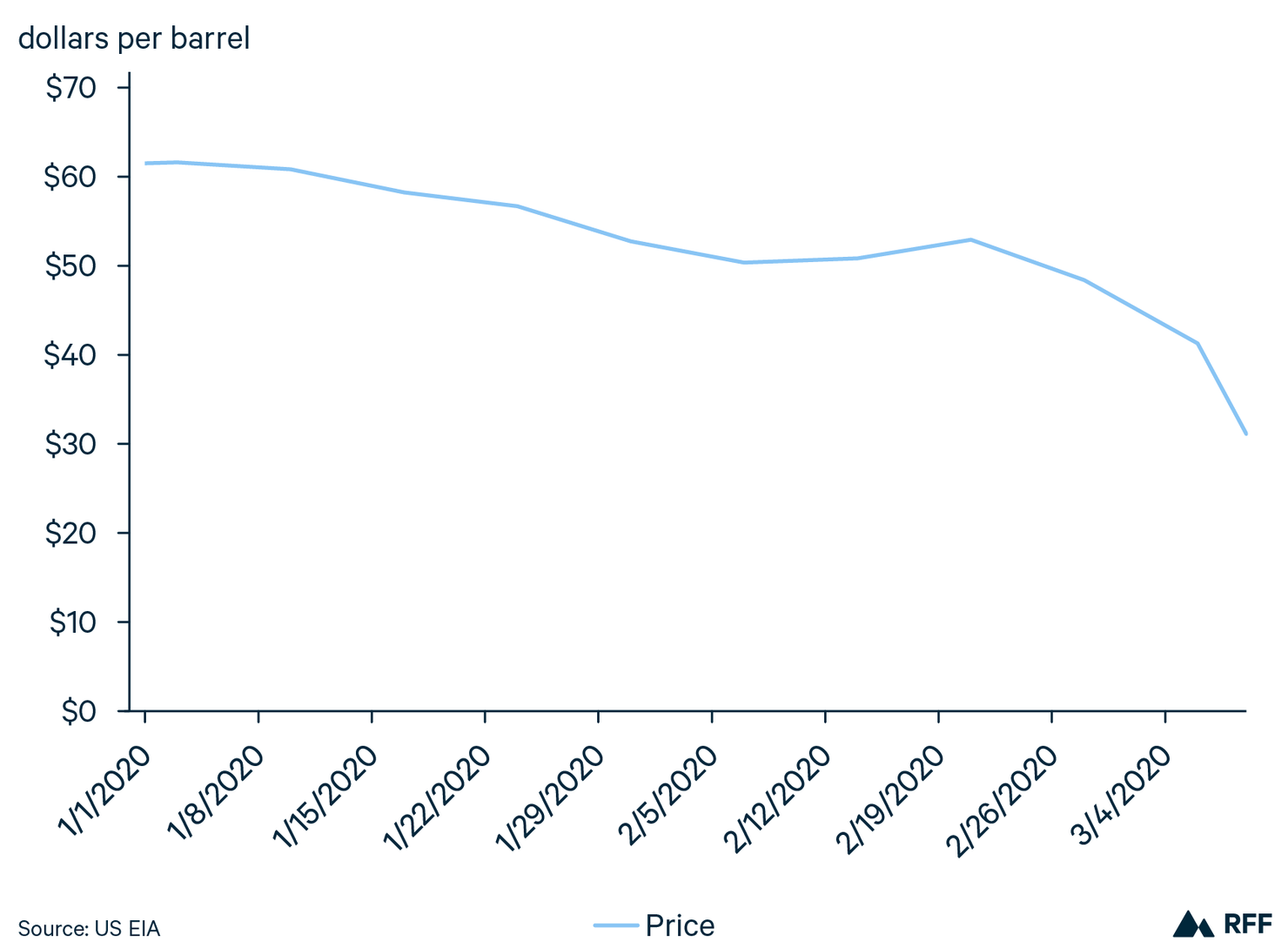

In what may be a first, global oil markets are simultaneously experiencing two major shocks: a dramatic drop in current (and expected future) demand, and a dramatic increase in supply from the world’s two largest crude oil exporters. The results are clear in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil price

Much lower for much longer?

Since the oil price shocks of the 1970s, US policymakers have sought to avert petroleum price spikes like vampires avoid garlic bread. Because the United States was then the world’s largest importer of crude oil, and exported almost none, a price spike meant unambiguously negative economic impacts nationally. Plus, the prominent display of gasoline prices on heavily trafficked street corners from Tarrytown to Temecula means that drivers are constantly reminded of the pain they will feel the next time they pull in to fill up.

But today, in the wake of the shale revolution, the economic effects of oil price shocks are more nuanced. While long-pumping oil regions in parts of Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, California, and elsewhere have always benefited from high oil prices, the more than doubling of US crude production over the last ten years means that a much larger chunk of the country now experiences the whipsaw of boom-bust oil prices. Since 2010, crude production in Texas and North Dakota has roughly quadrupled. In New Mexico and Colorado, it has more than quintupled. In 2010, US net imports of crude and refined products were about 10 million barrels per day. As of early 2020, the United States is a net exporter of crude and products.

This growth in production has meant more areas are reliant on oil as a local economic driver, supporting not just capital investment and jobs, but also schools, roads, health services, and much more. The last time oil prices plunged, in late 2014, the subsequent bust created economic hardship and budgeting challenges for local governments in places like North Dakota and West Texas. But after reaching lows of around $30 per barrel (bbl) in early 2016, US benchmark (West Texas Intermediate) oil prices were back above $50/bbl by the end of the year, helping to resuscitate the struggling oil patch.

This time around, because of the confluence of shocks from both the supply and the demand sides, and because OPEC+ may not return to managing prices for some time, this bust may be much more painful. Unlike previous decades, when an oil bust hurt oil regions but helped the economy as a whole, the larger footprint of the US oil industry means that a downturn that dips lower and lasts longer may be a drag on the broader US economy, adding to the woes brought about by COVID-19.

Think globally, act locally?

As policymakers wrestle with how to respond to the economic consequences of COVID-19, what, if any, policies may be useful in supporting the communities of the oil patch? Recent reports suggest that the Trump administration is considering action to support struggling domestic oil and gas companies in what some are referring to as the “shale-out.” But supporting the communities and workers—rather than the shareholders—hit hard by the bust is, to many, a more justifiable intervention. Despite the fact that presidents Obama and Trump have both celebrated the economic and geopolitical benefits of the shale revolution, no federal policies exist to help regions reliant on oil manage the ups and downs of a famously volatile industry.

In a 2019 report jointly published between RFF and the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, Jake Higdon, Ron Minsk, Alan Krupnick, and I made a case for a modest federal intervention to help oil patch economies diversify. We suggested that a small interagency team could support oil-producing regions gain better access to existing federal economic development funds from agencies such as the Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA). We also described a more aggressive approach, where Congress could appropriate funds for economic diversification efforts in oil-producing communities (likely administered by the EDA), as it has done for struggling coal communities.

However, these policy approaches would not provide the short-term local economic stimulus that many communities in Texas, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and elsewhere may be hoping for. Instead, the purpose of such policies is to support economic diversification over the longer term, weakening the blow of the next oil bust in these communities. Regardless of what happens over the coming days and weeks, such economic diversification strategies can help soften the landing in oil country when the bottom of the barrel falls out.