In September, the US Department of Energy released a funding opportunity announcement for its Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs program. Earlier this year, the agency requested feedback on the program from interested groups. In this new installment of an ongoing blog series, Resources for the Future scholars summarize the feedback from a selection of respondents—clean-hydrogen end users—and examine how the funding announcement addresses their comments.

In September, the US Department of Energy (DOE) released a funding opportunity announcement that called for hydrogen hub (H2Hubs) proposals in accordance with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This $8-billion program will support the production, processing, delivery, storage, and utilization of clean hydrogen in multiple hubs across the United States.

Months prior to announcing this funding opportunity, DOE issued a request for information to help guide the development of the H2Hubs program; over 300 groups responded. This blog post is the second in a series of articles in which we analyze the comments that have been submitted by leading organizations. Here, we look at comments submitted by hydrogen end users (often known in the industry as “offtakers”) and examine the issues and concerns that they’ve raised in their responses and how their concerns were addressed in the DOE funding opportunity announcement.

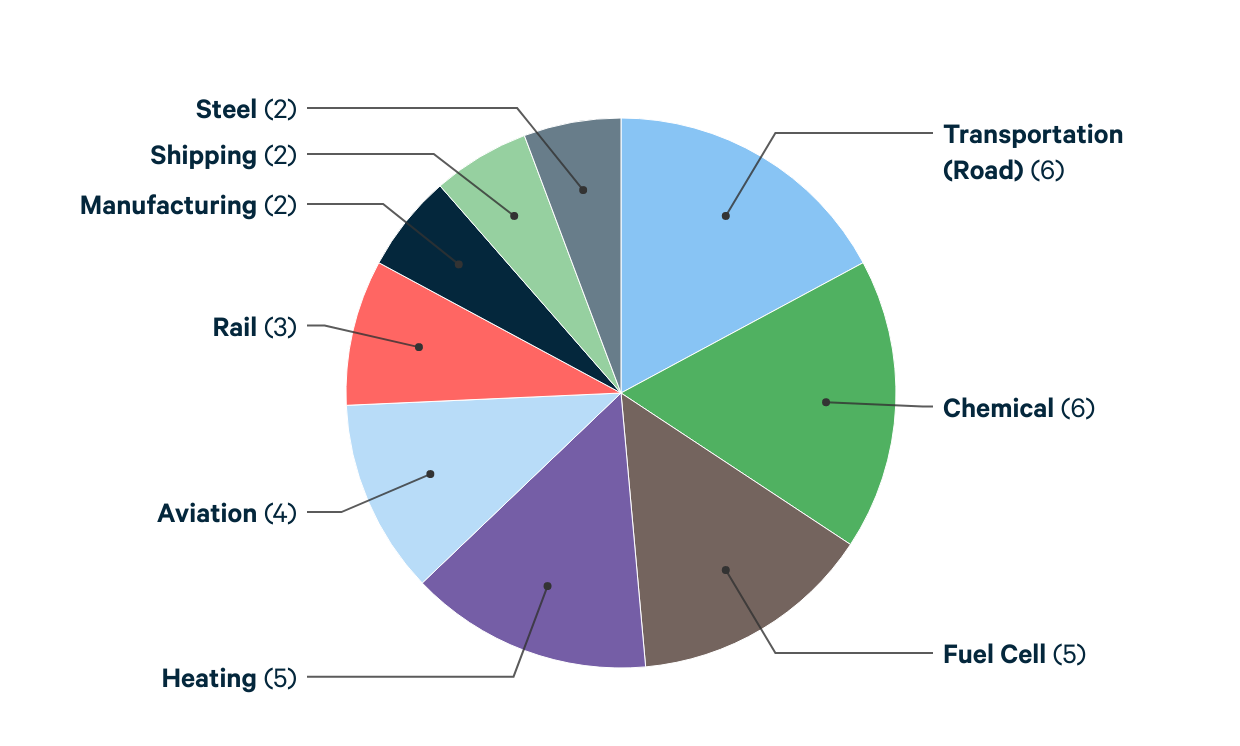

Figure 1 shows the hydrogen end users that responded to DOE’s request for information. Most vocal was the transportation industry, with 20 responses from groups such as fuel-cell truck manufacturers and producers of alternative aviation fuels. Additional responses came from the chemical sector (6), the heating sector (5), the iron and steel sector (2), and other manufacturers (2). Although the H2Hubs program requires the demonstration of hydrogen uses in the residential and commercial heating sectors, few actors in those sectors responded.

Figure 1. Responses from Hydrogen Fuel End Users to a Request for Information from the US Department of Energy

The Need for Supporting Hydrogen End Uses

One of the main concerns raised by potential end users is the lack of incentives for adopting hydrogen compared to incentives for other fuels and feedstocks. Many respondents highlighted that the cost difference remains large between clean hydrogen and fossil fuels such as natural gas or diesel. Respondents also called for federal support through financial incentives to ensure demand for the clean hydrogen produced by H2Hubs.

Some commenters argued that the creation of a low-carbon fuel standard, similar to the one used in California, would help foster supply and demand for clean hydrogen nationwide. Industries with high fuel usage, such as the marine transportation sector, were proponents of this solution. Respondents also favored investment tax credits or other tax incentives for capital investment.

Overall, hydrogen end users pushed for overarching policies that can trigger the faster adoption of low-carbon solutions and meet the expectations for low-risk investments by venture capitalists and other financial institutions involved in the clean energy transition. The clean transportation sector, for instance, called for the mandatory adoption of zero-emissions vehicles at the federal, state, or local level. Various forms of carbon pricing also were put forward as whole-economy solutions.

DOE addresses many of these concerns in the funding opportunity announcement by including end users in the definition of a hydrogen hub; the agency goes even further by stating a preference for hubs that balance supply and demand—in other words, hubs where the vast majority of the hydrogen is used within the hub itself.

In addition, the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in July this year, includes federal incentives for developing hydrogen production and using hydrogen in manufacturing processes. The act provides a production tax credit (called “45V”) for clean hydrogen, which can reach a maximum of $3 per kilogram of hydrogen produced. The bill also increases the value of the 45Q tax credit for carbon capture, utilization and storage activities. These tax credits are relevant for “blue” hydrogen, which is hydrogen fuel that is produced with natural gas (or coal) whose carbon dioxide emissions are captured on-site.

Beyond the subsidies for hydrogen production, the Inflation Reduction Act includes investment tax credits and other provisions that can help improve the economics of hydrogen for end users, such as funding for research and development that’s related to advanced clean manufacturing, federal procurement of construction projects that use clean steel and cement, and funding for a green bank.

Offtake Agreements

DOE suggested in its notice of intent, and previously in its request for information, that offtake agreements (i.e., agreements for end users to purchase the hydrogen produced by a hub) would be required in all hub projects as a way to match the supply and demand of clean hydrogen, stabilize prices, and generate further private investment. End users disagreed, however, on the need to require offtake agreements in the application process. On the one hand, without certainty about future clean-hydrogen prices, hydrogen end users may not want to commit to long-term contracts. On the other hand, agreements decrease the risk for producers and investors without preventing future expansions of a hub. DOE settled this issue by requiring finalized offtake agreements within the first four years of the project, by the development phase of the hub rollout.

To increase the number and reliability of offtake agreements, hydrogen end users suggested various policies and instruments. For instance, they wrote that the federal government could back offtake contracts with financial guarantees for hydrogen end users or with backstop mechanisms that guarantee alternative channels for consumption in the form of injection into natural gas pipelines.

One commenter noted that direct injection into natural gas pipelines also could help compensate for timing variability or unanticipated project delays, noting that hydrogen end users want “federal support to secure direct injection contracts into local natural gas pipelines for the projected commercial price of the clean hydrogen produced, up to a certain percentage of the total production.”

Although [the National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap] will help prepare hydrogen suppliers and hydrogen end users for a future competitive market, end users emphasized in their comments the need to plan production growth in parallel with infrastructure deployment and increased offtake capacity.

While divided on the offtake-agreement issues, respondents broadly agreed on the need for multiple and diverse hydrogen end users, which can help maximize the use of infrastructure, generate economies of scale, spread benefits geographically, and decrease risks for hub actors. Longer-term contracts are more likely to be agreed upon now that the Inflation Reduction Act has offered federal support for clean hydrogen, but end users also highlighted the need to decrease unknown variables in commercial agreements by identifying all regional factors that might affect the hub activities.

Many of these concerns about offtake agreements are addressed in the funding opportunity announcement, which states that end users are eligible to participate in the hubs themselves. In addition, the level of participation of hydrogen end users, measured through the degree of their integration in the hub planning process and the letters of commitment they provide, is included in the application selection criteria. Thus, at least some offtake agreements probably will involve contracted end users.

Cooperation versus Competition

Many end users called for a cooperative approach among participants in the hydrogen market. For novel uses of hydrogen that are in the early stages of development, some respondents suggested industry-level cooperation to establish best practices for clean-hydrogen use. Some also called for the involvement of other DOE offices (e.g., the Advanced Manufacturing Office) to develop and adapt clean hydrogen for industrial heating, shipping, and aviation, among other uses. Given that hydrogen is presented in DOE’s Industrial Decarbonization Roadmap as one of the key strategies for reaching net-zero emissions, end users can expect future innovation support from DOE offices in addition to the current funding opportunity announcements that cover clean hydrogen–related innovation.

The National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap from DOE provides guidance for the agency’s plans for advancing hydrogen. Although this new document will help prepare hydrogen suppliers and hydrogen end users for a future competitive market, end users emphasized in their comments the need to plan production growth in parallel with infrastructure deployment and increased offtake capacity: “The key for making H2Hubs successful and sustainable is building a robust, evolving roadmap that sees gradually increasing offtake and a broadening diversity of offtakers [i.e., hydrogen end users] across different sectors.”

Overall, communication within and between hubs—as well as with industry groups, DOE offices, and federal research institutions—seems to be paramount for hydrogen end users. The funding opportunity announcement highlights the need for engagement with all the stakeholders to better inform the design, development, and operation of hubs, and to better distribute hub benefits. DOE also will collect and disseminate data related to hub performance, but the agency does not seem to be organizing information sharing among hubs. According to another respondent, “Collaboration over competition must be favored to leverage successes, while the early hydrogen market demand is far larger than any competitor could dominate, at least for the next five or so years.” However, hydrogen end users agreed that this cooperative approach should be phased out over the course of the program, given that one of the goals of the H2Hubs program is to demonstrate the sustainability of clean hydrogen markets and the potential for a national clean hydrogen network.

Geographic Location

A broad consensus exists among hydrogen end users that hubs should be located near existing transportation hubs (e.g., ports, highway intersections, and airports) and industrial hubs. Placing H2Hubs near these two types of locations will increase the number of potential hydrogen end users and decrease the risk of unreliable and insufficient demand. As it happens, the funding opportunity announcement encourages applicants to leverage existing facilities and infrastructure, which likely are located within or near transportation and industrial hubs.

In addition, a favorable environment for hubs can arise from preexisting state and local climate policies and incentives for the development of a low-carbon economy. Because DOE’s 50 percent cost-share requirement includes state, local, and private funding, applicants in climate-friendly regions may well submit strong H2Hub proposals.

Conclusions

Insights from this subset of respondents point to their concern about a lack of support for the adoption of hydrogen technologies for novel and developing uses, uncompetitive costs, and a potential first-mover disadvantage, given the technology risks that early adopters face. With the funding opportunity announcement from DOE and congressional legislation, some of the concerns from end users surely have been addressed. Time will tell if these efforts can assure the viability of future hubs and the success of this program.