More than five million acres have burned across the West Coast in this year’s unusually severe wildfire season. Billowing smoke has traveled across the country, degrading air quality as far east as Washington, DC, and amplifying health risks for a nation still grappling with COVID-19.

Many factors contribute to the unique intensity and reach of this year’s blazes. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has emphasized the role of climate change in exacerbating wildfire risks, while President Donald Trump has largely blamed poor forest management. Bureaucratic hurdles—such as the court-mandated requirement that federal units consult each other before implementing forest management strategies—can complicate relief efforts, too, according to the sponsors of one bipartisan Senate bill.

To provide further context on how policymakers and forest managers can effectively mitigate the mounting threat of wildfires, RFF’s Ann Bartuska, David Wear, and Matthew Wibbenmeyer share their insights. All three researchers sat down together to discuss the relative effectiveness of different wildfire response strategies, and an edited version of their conversation is below.

Resources: You all are well aware of the cyclical nature of wildfires. But against this backdrop of another expected wildfire season in the western part of the United States, why have this year’s fires generated more attention? Why have recent discussions about forest management been especially salient?

Matthew Wibbenmeyer: This year’s fire season has been especially extreme. Five of the 10 largest fires in California’s history have occurred this year. California is making a habit of breaking records with its wildfires, but that’s a pretty notable series of fires. Oregon experienced a really dramatic series of wildfire events, too. The smoke that went along with these fires was extremely thick and widespread and engulfed major population centers on the West Coast for weeks.

Ann Bartuska: And because of COVID-19, we’re all much more aware of our setting and our space—so not being able to go outside and do things because of smoke is more noticeable. People in Massachusetts have told me that their sky has been hazy for days, and that’s really unusual. As Matt said, there’s a widespread nature to these fires, but also a wider swath of people—not just those immediately by the fire—who have been exposed to the consequences of the fire.

David N. Wear: This season has been especially impactful, but it’s important, too, to think about the last decade or so and how many extreme fire seasons we’ve had in that stretch of time. In just the last five years, we’ve had the Okanogan Complex Fire in Washington; we saw the big impacts on Santa Rosa; and we had the destruction of Paradise, California, which brought substantial human and property losses.

AB: To follow that thread: We have a major forest issue, but we also have the issue of where people are being allowed to build homes. We really have to take a hard look at how we’re ensuring that people are aware they’re putting themselves in harm’s way. Already, they’re starting to rebuild these same communities, and we’re just going to have this same cycle again in 10 years when the forest regrows and fills in and there’s another drought. We’ve got this terrible human cycle going on.

Whether forest thinning and prescribed burns are effective strategies for reducing wildfires has been a heated debate for decades. How can we productively discuss the best ways to implement these strategies, given the longstanding controversy? Has this perennial debate changed or shifted this year, given how exceptional wildfire seasons have been recently?

AB: We do actually have data to show that if you do proper thinning followed by prescribed burning to get a fire-prone forest to the right density, then you can really keep the fire burning on the ground with less intensity and less spread. The challenge is that you have to have permission to burn, and you have a very short burn season for prescribed fires. You also have to have the permission to harvest, which presents challenges, because people are concerned about cutting trees. It’s not complicated, but there are multiple places where there has to be what I call a “social license” to be able to accomplish the task.

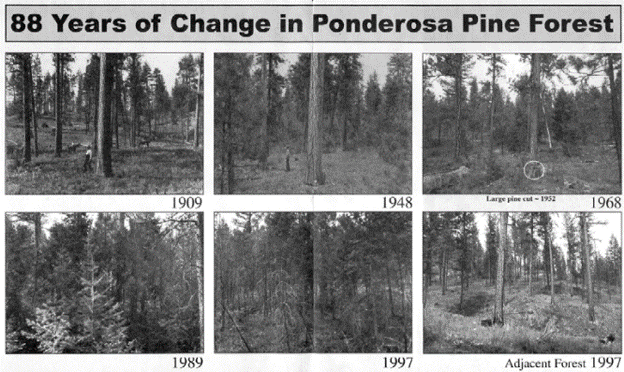

Photographs taken from a single vantage point, from 1909 through 1997, which show changes to the landscape that result from fire exclusion, large pine removal, and forest management. Original image credit: Smith, Helen Y., and Stephen F. Arno. 1999. Eighty-eight years of change in a managed ponderosa pine forest. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-23. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Reformatted image credit: Northwest Center for Sustainable Resources.

MW: I would add that there’s not just one controversy surrounding forest management and forest thinning. Thinning can be controversial, because when some people hear “thinning” they perceive that to mean large-scale timber sales. And in some cases, it does mean that—so there’s a distrust that’s built up among the environmental community about the idea of forest management. But the reality is that thinning really is needed to restore forests and reduce wildfire risk in some areas. There’s a real tension there.

And with prescribed burns, there’s an entirely separate issue. People have in some cases been wary of prescribed burns because they are perceived as risky and because they produce smoke. But as fires are getting more intense, I think people are probably more willing to come to the table to find solutions around both of these things, realizing that these are real problems that need to be solved.

DNW: Everything that Ann and Matt said are right on. But I also think about the tools that managers have: a drip torch, a chainsaw, and maybe a planting hoe. So, you can remove vegetation either by cutting it and removing it from the site, or you can burn vegetation under controlled conditions, or you can plant different species. But ultimately, the question is: How do you manipulate vegetation to generate a fire-resilient landscape? It seems to me that we need to put more focus on what the desired outcome is, and understand that there are limited tools for manipulating the vegetation to get it to that point. If we have a market for selling some of the material that’s removed in the process of building out a fire-resilient landscape, then that allows budgets to go further and allows us to treat more area.

What evidence do we have for the effectiveness of forest thinning versus other strategies for reducing wildfire prevalence?

AB: There is very clear evidence that thinning to reduce the amount of hazardous fuels does work. A concern that has been raised is that sometimes when you thin, only the wood gets taken out, and then the branches and residuals are left lying in the forest, and that creates a forest debris bed. While that may be true in some cases, the Hazardous Fuels Reduction funding that’s made available actually requires that the material be removed or burned on site. So, that concern is diminishing.

DNW: This is an incredibly complex question. Each forest type is subject to its own fire regime, and all forest managers are working in the context of adaptive management, especially as we face climate change. We know what treatments worked well in the last decade, but going forward, we don’t have as much knowledge. As Ann described, the effectiveness of thinning and prescribed burns is our working hypothesis, and it seems to be confirmed in many places, but it will be modified and adapted as we go forward.

A forest before (above) and after hazardous fuels reduction. Image credit: US Forest Service

AB: Another complexity here is that if you have an insect outbreak that goes through the forest stand and kills or severely weakens the remaining trees, no amount of thinning can prevent that. That’s why we saw some of these really huge fires in Colorado several years ago, because almost the entire pine community had been affected by the bark beetle, so you just had thousands and thousands of acres of trees that were dead and dying. Exogenous factors can affect even the healthiest forest.

What’s the right way to think about forest management and the extent to which certain management practices have contributed to these wildfires? What policies or management approaches have been recommended at the scale of the US government and for forest organizations? Which of those recommendations stand out?

MW: Fires can occur only if there are fuels to burn, and if those fuels are dry. In some places, especially in dry western forest types like ponderosa pine forests, forest management has contributed to the accumulation of fuels, leading to more intense and severe fires than have typically occurred in these forest types. In these places, forest restoration can make a big difference toward reducing fire risk and restoring ecosystem health.

However, the degree to which forest management has contributed to wildfire activity in recent years probably is overstated. For one, not all wildfires are burning in what we typically think of as “forest.” In Southern California, wildfires frequently burn through chaparral, a shrubland ecosystem in which forest management is really not the issue.

AB: It’s not only about the vegetation and climate; the societal context also is important. A lot can be done to mitigate fire impacts if more Firewise practices are used by homeowners and required by communities. But realistically, no houses should be permitted in some fire-prone areas where access is limited.

How can policymakers align the environmental and public safety goals of wildfire prevention with the economic goals of forest resource management and timber harvesting?

DNW: It’s nearly impossible to think of these as two separate sets of objectives. Wildfires now dominate every element of public forest resource management. Fire risk mitigation protects and enhances forest resource values and is also the path toward reducing the massive costs of fighting wildfires. Stabilizing and building resilient landscapes also stabilizes local economies and communities.

A forest before (above) and after hazardous fuels reduction. Image credit: US National Park Service

AB: We have to do something differently, because we now have had years of putting fire suppression first. The government has been willing to fight fires, and it doesn’t matter how much it costs; we’re going to pay for it. But we should flip that on its head and say, “No, if we did more proactive management, if we work with communities, if we require Firewise communities, if we work with the insurance industry so that communities manage risks correctly, then we can balance.” To be able to work at that front end is really just a critical rethinking of how we approach the problem.

I may also have a cynical view of the current situation: I was on the interagency wildfire team in 1995, which was triggered largely by the Sunrise Fire on Long Island, and then I was on one in 2000, after the Cerro Grande Fire. In both cases, we came up with a plan to change the paradigm. Well, it’s 20 years later, and we’re still in the same place. What’s the institutional drag that prevents us from actually making that shift? We have some ideas of what needs to be done, and it’s just that the political will and the funding to be able to do that remain obstacles.

DNW: I’ll add that to move the needle on this issue requires a huge up-front investment in modifying these landscapes. It requires a structural change in our approach. The need for fuel treatments is an order of magnitude or two beyond the ability of current budgets to support. We need to come up with creative approaches to finance forest restoration, whether from the public or the private sector, to bring fuel treatments up to an effective scale.

Climate change threatens to amplify wildfire risks and make wildfire seasons more intense. How can we implement empirically based recommendations now, given the uncertainty of future change? To what extent do our approaches need to be adaptable?

DNW: This question goes back to the notion of adaptive management. We have uncertainty about the future climate, and we have uncertainty about how future forests will respond to climate change. It’s important that we understand that we’re managing based on working hypotheses and moving forward with management, but trying to adapt management strategies based on experience and growing bodies of knowledge.

AB: Universities have been working on that knowledge base, and they’ve also been looking at how wildfire, insects, disease, and climate are affecting these forests. It’s not always well-known, but we’ve been doing climate change research since 1990 in the United States. We put a lot of money in the US Forest Service, and the US Department of Agriculture and the US Department of Interior have done a really incredible job at looking at the role of climate and forests. We have a very strong science base for the decisions that we want to take from the biophysical side. The social-economic side is the bigger challenge.

What’s the institutional drag that prevents us from actually making that shift? We have some ideas of what needs to be done, and it’s just that the political will and the funding to be able to do that remain obstacles.

Ann Bartuska

DNW: I think you’re right, Ann. There is a really good knowledge base, but I’d argue that it’s going to take more investment in an ongoing effort to test those hypotheses as climate evolves.

In our changing world, how much do we need to shift our efforts from wildfire prevention more toward damage control and wildfire adaptation? Which of these options are economically optimal? Which are politically viable?

MW: Unfortunately for California and other western states, wildfires are here to stay for the foreseeable future. And as we now know, in some cases, wildfire exclusion only makes the problem worse. We need to learn to adapt to wildfire and live with it. This means increased use of prescribed burns and managed fires as conditions permit, and it means reducing construction in highly risky areas.

AB: Agencies and organizations that are involved in managing our forestlands have been trying to shift to prevention and management and away from suppression, and I do believe that prevention is cheaper than suppression in the long run. For one, you’re preventing damage, which has its own cost—it’s not just the cost of suppression.

But are these efforts politically viable? At the moment, there does seem to be a lot of interest, and many bills before Congress are promoting more up-front work.