Addressing climate change and pollution requires a shift to electric vehicles and better fuel economy—but gasoline and diesel sales are key funding sources for US road infrastructure. How can we close that growing infrastructure funding gap?

As researchers and policymakers have known for years, US transportation infrastructure spending is on an unsustainable path. The Biden administration recently announced new policies that can improve vehicle fuel economy and spur the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), which will advance our goals of limiting global warming and reducing local air pollution—but these policies will exacerbate the large and growing gap between our available revenues and the needed expenditures for road infrastructure.

Federal and state taxes on gasoline and diesel raise almost $90 billion per year for roads, bridges, and other transportation infrastructure. But for decades, the US Congress has failed to adjust federal tax rates on gasoline or diesel to keep up with inflation. As a result, the federal Highway Trust Fund (HTF) has approached insolvency repeatedly, and Congress has had to transfer more than $200 billion from general revenues since 2008 to keep the HTF afloat. As gasoline-powered vehicles fade into the rear-view mirror, a new model for funding US road infrastructure is needed desperately.

In a new working paper released this week, my RFF coauthors Joshua Linn, Virginia McConnell, Sophie Pesek, and I examine several routes that the federal government and states can consider as they seek to address not only climate change, but also ensure that roads and bridges are adequately funded.

What Are Our Options?

In recent years, states and the federal government have begun experimenting with programs that collect taxes from drivers based on vehicle miles traveled (VMT)—the distance that people drive—rather than the amount of fuel that people buy. This approach will tend to produce a more stable stream of government revenue, because while enhanced fuel economy standards and the rise of EVs will reduce gasoline consumption, the effects of increased fuel economy on VMT are less direct; in fact, people with gasoline-powered cars that are more fuel-efficient likely will drive more.

To understand how different tax designs might affect future government revenue, vehicle sales, driving behavior, emissions, and more, we turned to RFF’s Vehicle Market Model, which covers all light-duty vehicles owned by households in the United States. (The model does not cover commercial vehicles like heavy trucks or fleet vehicles like rental cars—important areas for future analysis.) We used the model to compare six scenarios that we grouped into three buckets, and we varied key elements to account for changes in fuel economy standards and other factors. These buckets were the following:

- two “business-as-usual” scenarios, in which federal tax rates remain flat, and state tax rates rise at the rate of inflation (as they have, more or less, in recent years)

- three “HTF” scenarios, which set tax rates at levels high enough to keep the HTF afloat, but with different fuel economy standards, and one scenario that funds the HTF by replacing all fuel taxes with a tax on VMT

- one “externality” scenario that sets the tax rate equal to the full external costs of driving, including the damages that drivers impose on society through carbon dioxide emissions, “local” air pollution, traffic congestion, and accidents

How Much Will This All Cost?

Based on our HTF scenarios, we estimate that federal gasoline tax rates would need to roughly triple (from 18 cents to 54–58 cents per gallon), and state tax rates would need to grow by around 40 percent on average (from 27. cents to 38.0–41.0 cents per gallon) to adequately fund US roadways. (Check out the paper to learn how we define “adequately.”)

These HTF scenarios also included a hypothetical VMT tax on EVs, which we set equal to the amount that the average gasoline-vehicle driver pays on a per-mile basis for federal and state taxes (2.0–2.5 cents per mile). One of the questions we were curious about was whether this new EV-only tax would deter consumers from buying EVs. (Spoiler alert: it doesn’t.)

In our HTF scenario that swaps out the gasoline tax for a VMT tax for all vehicles, we estimate that a tax rate of 3.1 cents per mile would be sufficient to maintain the roads.

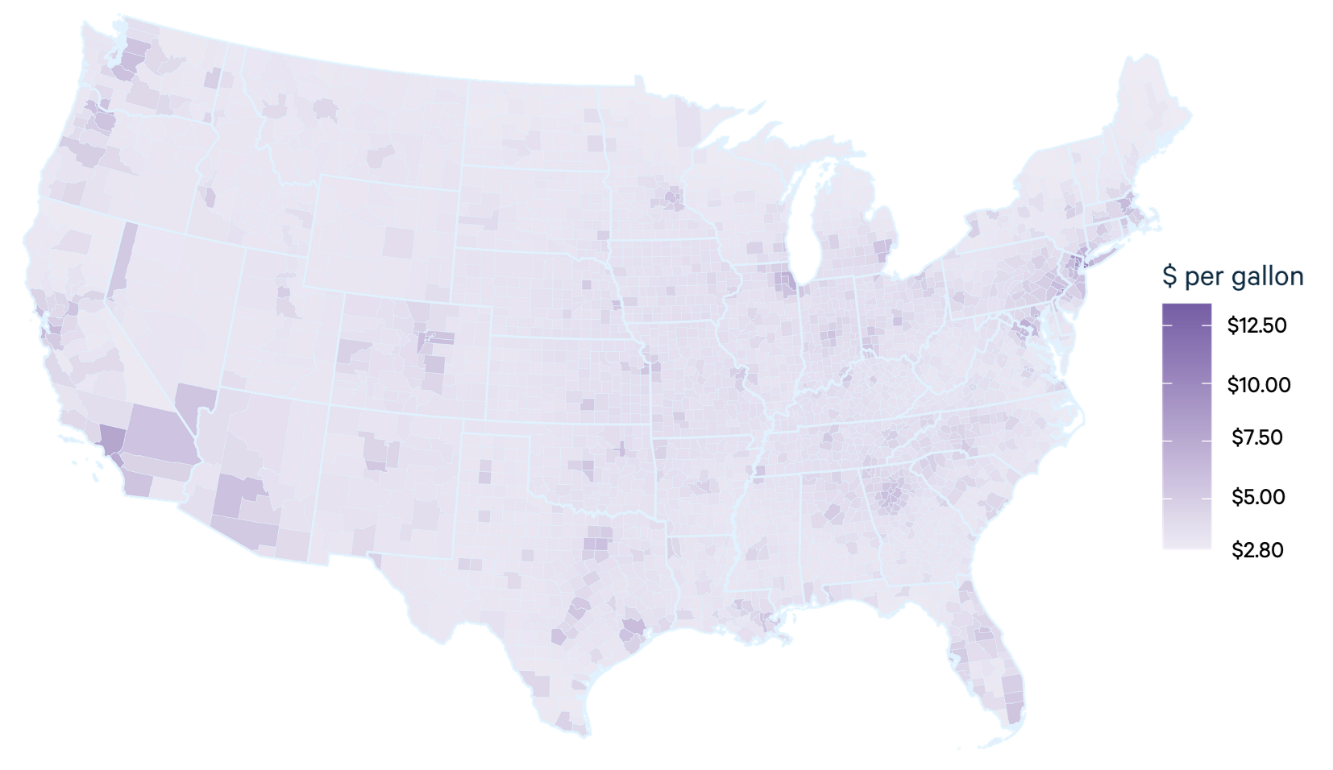

Another contribution of this analysis is that we developed an updated estimate for the external costs of driving—which we used as the tax rate for our “externality” scenario—which was considerably higher than most previous estimates in the literature. These external costs are high in part because we used an updated value of the social cost of carbon developed by RFF and others, and because we varied the external tax depending on where people drive. This geographic variation is important because the external costs—particularly for air pollution and traffic congestion—vary enormously between big, crowded cities like New York or Los Angeles, and rural areas where these costs are much lower.

Table 1 summarizes our estimates for the external costs of driving, with damages from greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution based on gasoline consumption, and traffic congestion and accidents based on VMT. We show all four components in dollars per gallon and dollars per mile using a conversion rate of 24 miles per gallon.

Table 1. Summary of External Cost Estimates (2021$)

Figure 1 illustrates the external costs at the county level. The enormous variation is clearly visible, ranging from lows of $2.83 per gallon in rural regions to highs above $10.00 per gallon in urban places like New York and Los Angeles. The national average is 16 cents per mile for gasoline vehicles ($3.85 per gallon) and 6 cents per mile for EVs, which pay only the congestion and accident portions of the tax.

Figure 1. Full External Costs of Driving by US County

When the Rubber Meets the Road

So, how do these different policies affect the things we care about? Although the modeling is complex, the answers are quite straightforward.

In terms of road funding, a business-as-usual trajectory drives us into a ditch, while the HTF scenarios provide clear routes toward maintaining our road infrastructure. If driving were taxed at the full external costs, the government would have more than enough cash to fund road infrastructure and could use the leftovers to reduce other taxes like the payroll tax, fund public transportation, build more EV charging stations, or support whatever else could use the funding.

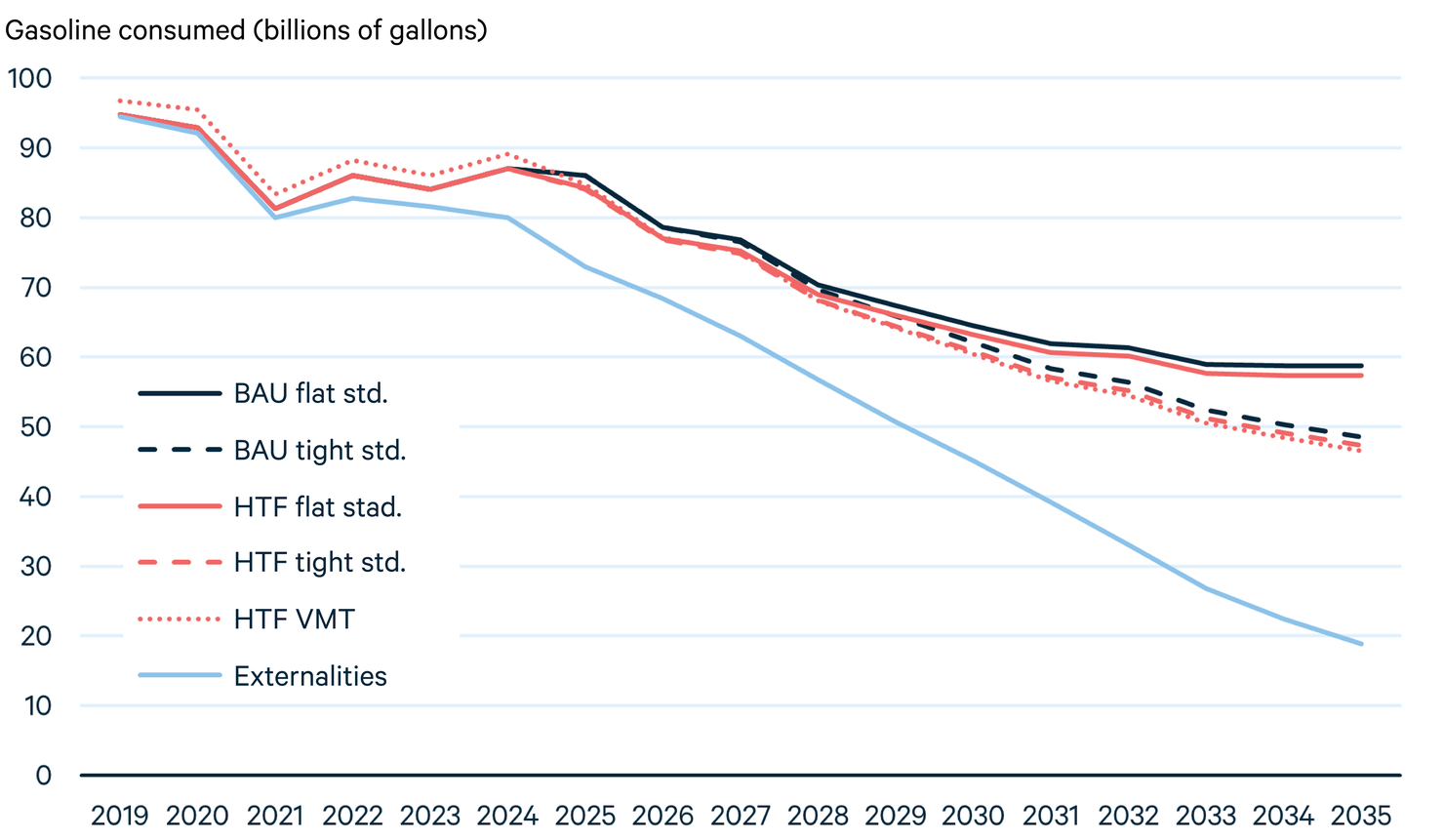

For greenhouse gas emissions, we find that enhanced fuel economy standards, like those announced this week by the US Environmental Protection Agency, reduce emissions considerably—but tightened standards also reduce government revenue; hence, the appeal of a VMT tax. Putting a price on the full external costs of driving leads to a much deeper reduction in gasoline consumption and emissions. Figure 2 shows gasoline consumption for household vehicles under our six scenarios. In this figure, gasoline consumption is a proxy for emissions, because we do not account for the emissions associated with the electricity that charges EVs—an important issue that future work can incorporate.

Figure 2. Gasoline Consumption of Household Vehicles

We also examined the effects of different tax policies on new car sales and find that, as noted above, adding a new VMT tax specifically for EVs has virtually no effect on EV sales. This finding suggests that a mix of taxes, in which gasoline-fueled cars pay a gasoline tax and EVs pay a VMT tax, could fund road infrastructure without substantially slowing the transition to more EVs. Of course, this outcome will depend on the level of the tax rate that policymakers decide on, and a higher VMT tax for EVs could have larger effects.

Another interesting finding from our HTF scenarios is that tightening the fuel economy standards slows the growth of EV sales. That’s because more fuel-efficient vehicles are less costly to drive than their gas-guzzling counterparts, which reduces some of the economic incentives for consumers to go electric.

Under our scenario in which all drivers pay the full external costs of driving, EV sales approach 100 percent of new car sales by the early 2030s. This finding reflects the much higher costs that drivers of gasoline vehicles would pay relative to EVs, which are not subject to two parts of the full external tax: carbon dioxide emissions and local air pollution. To ensure that rapid growth in EV sales also delivers benefits on climate and air pollution, the electricity sector will need to accelerate its own transition away from emitting sources and toward a clean power grid.

What’s Missing

Although we examined a wide range of policy options and outcomes in our paper, important gaps remain and offer opportunities for new research.

First, our analysis does not focus on how different transportation tax policies would differentially affect households and individuals across socioeconomic groups. Recent research has found that EV subsidies are quite regressive, and the gasoline tax is somewhat regressive, too (although the outcomes of the gasoline tax for different income groups are nuanced and pretty complex). Developing and implementing a new tax structure—whether a revised gasoline tax, a new VMT tax, or some combination of the two—should include careful consideration of how these policies affect low-income households, rural households, and others who may bear a disproportionate burden.

Second, our modeling tools don’t allow us to incorporate several important elements that could make a VMT tax more efficient. These factors include congestion pricing, for which motorists are charged for the congestion they cause in real time, and which is under consideration in cities such as New York. (In our model, congestion costs vary across counties, but not across time.) Similarly, future work could provide more detailed geospatial results (like in this nice paper by Cody Nehiba), given that congestion varies widely within counties. In addition, the ideal VMT tax would account for vehicle weight, which contributes to the severity of traffic accidents and road damage.

Summing Up

In short, a lot more research needs to be done to identify the right set of policies that can enable an equitable transition to a low-emissions transportation system. But one thing is clear: the current model for funding transportation infrastructure is broken. New policies that improve fuel economy and accelerate the shift to EVs are needed to address the connected challenges of climate change and local air pollution, but these changes will need to be accompanied by new revenue policies to ensure that transportation infrastructure is funded adequately and equitably.