The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) replacement of the Clean Power Plan (CPP)—the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule—is expected to be released in its final form by the end of June. In its initial proposal, EPA narrowed its pivotal determination of the “best system of emission reduction” for power plants to include only heat rate improvements (technological methods to increase the efficiency of coal plants and lower the amount of fuel used and carbon emitted for every unit of electricity generated) at coal-fired plants. However, projections from EPA’s regulatory impact analysis of the ACE rule produces a result that is seemingly at odds with the determination that heat rate improvements are the best way to reduce carbon emissions at power plants: EPA’s projections show that carbon emissions outcomes actually worsen as heat rate improvements strengthen. More on this below.

EPA’s ACE proposal had two major components. The first component, as mentioned above, addresses EPA’s legal obligation to regulate greenhouse gases from existing power plants by singularly targeting heat rate improvements at coal-fired plants, in lieu of a broader set of measures identified in the CPP. The second major component was a proposal to reform the New Source Review (NSR), an EPA program that requires new and modified power plants to obtain air pollution permits. EPA expects this reform will enable greater heat rate improvements at plants.

Previously, we analyzed EPA’s regulatory impact analysis projections of the proposed rule’s impacts and found that ACE could actually increase carbon emissions at many coal plants and cause higher sector-wide emissions in many states. Our paper, with coauthors at Harvard, Syracuse, and Boston Universities, focused on EPA’s scenario in which NSR reform would enable 4.5 percent heat rate improvements at coal plants. However, EPA is now expected to split the proposal by finalizing the ACE rule including only the first component and pursuing NSR reform separately. This opens up the possibility that ACE will be implemented without reform to NSR, so we decided to take a closer look at the EPA’s scenario in which NSR reform is not implemented and heat rate improvements of only 2 percent are available.

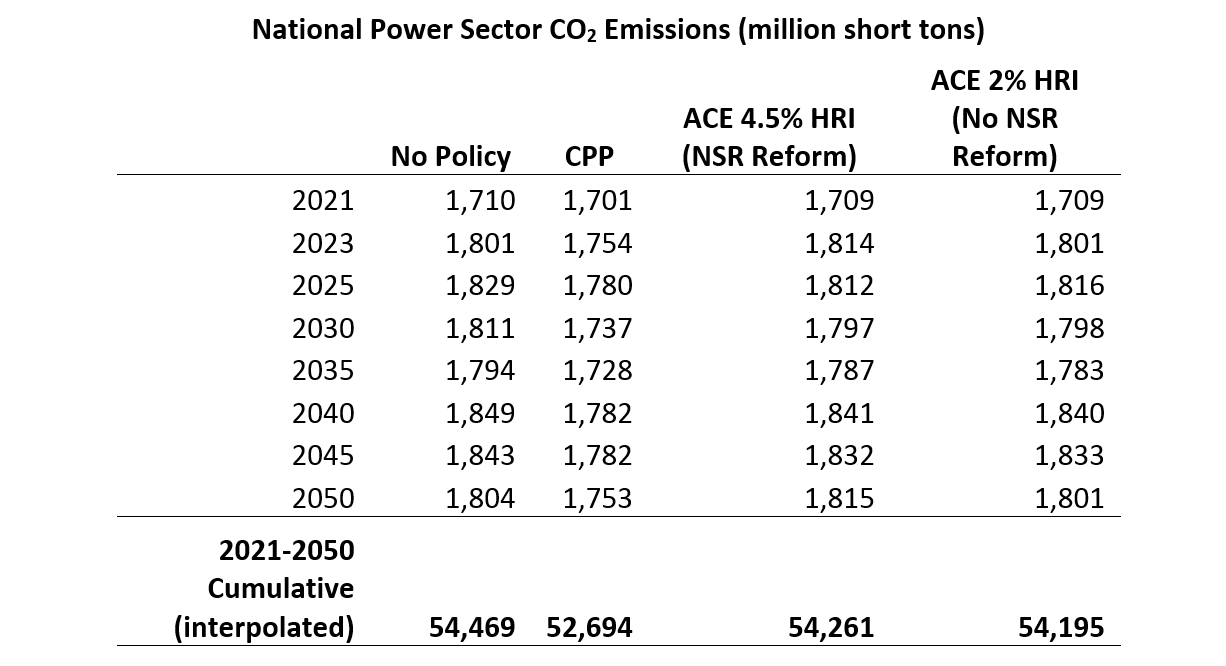

The results we found are not intuitive. Although a greater heat rate improvement at coal plants might be expected to decrease carbon emissions, the greater heat rate improvement case of 4.5 percent actually leads to higher carbon emissions compared to the 2 percent heat rate improvement case (see the table below). In other words, an ACE with NSR reform that would enable greater heat rate improvements is expected to have higher carbon emissions than an ACE without NSR reform. The same result is true for emissions of local pollutants sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. Both ACE scenarios are expected to have substantially higher emissions of carbon dioxide and local pollutants compared to the CPP.

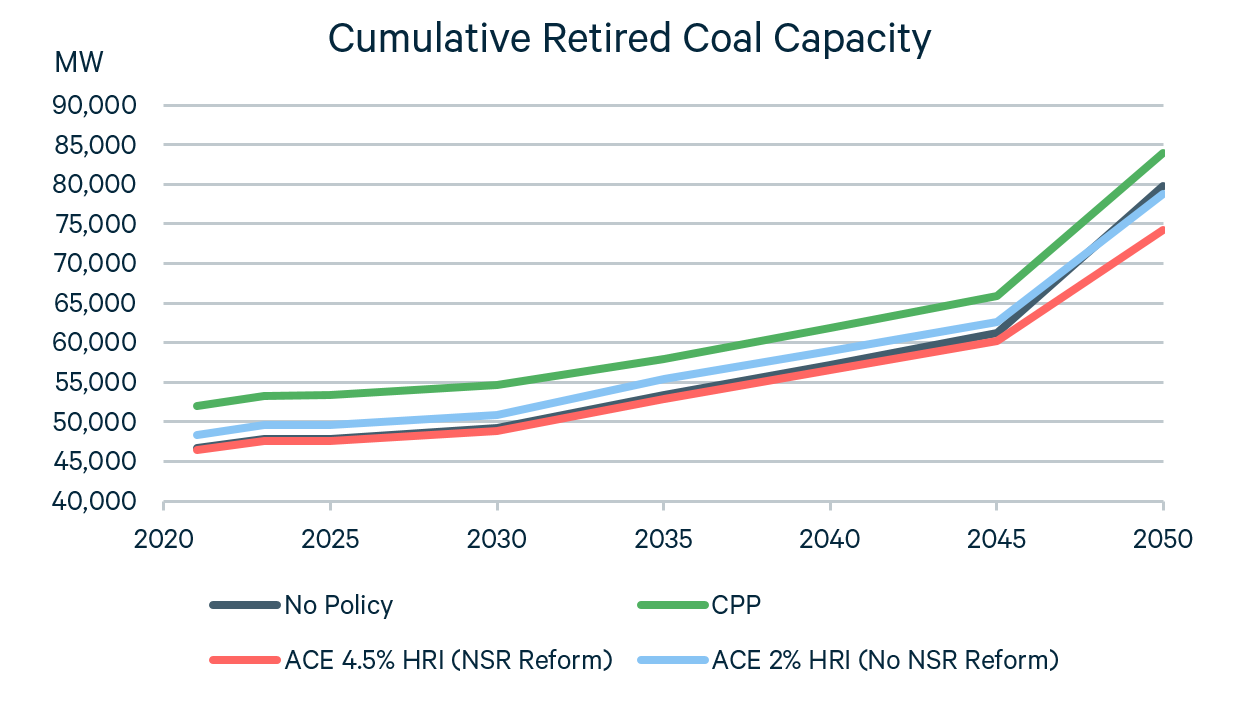

This surprising result is the rebound effect in action. Our paper explained that when coal plants invest in heat rate improvements and become more competitive, it can enable them to generate more electricity and delay retirement. This phenomenon is called the rebound effect. Indeed, coal-fired power generation is projected to be highest under the ACE scenario with NSR reform, and cumulative retired coal capacity (the decreased coal-fired generation capacity due to plants being retired) is projected to be lowest under that scenario (see figures below).

There are a couple important takeaways from these results. The first is that NSR reform may actually worsen ACE’s carbon emissions and air pollution outcomes compared to ACE without NSR reform. This complicates EPA’s stated justification for NSR reform, which is that it would enable coal plants to efficiently reduce their carbon emissions. Advocates of NSR reform have argued that NSR precludes efficiency investments in emitting facilities, leading to greater emissions than if NSR were not in place. However, EPA’s projections show that this is not the case here, and indicate that reforming NSR would lead to greater emissions under the ACE rule. This result suggests that EPA should consider the potential impacts of NSR reform on ACE emissions outcomes, whether or not NSR reform is pursued in a separate rule. If both ACE and NSR reform are implemented, this consideration is critical.

The second takeaway is that power sector emissions increase with greater heat rate improvements. In the ACE proposal, EPA reversed the findings of the Clean Power Plan—that a comprehensive, sector-wide approach is the best method to reduce emissions—and defined the “best system of emission reduction” for greenhouse gases from power plants as heat rate improvements at coal plants. But how can heat rate improvements be the “best system” if they would cause higher greenhouse gas emissions the more they are required?