We already live in an uncertain world because of climate change, and COVID-19 has only made the future even more difficult to predict. Global oil prices, state tax revenues, vehicle purchases, and transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions are all much lower than expected, following stay-at-home orders and the economic downturn.

Against this backdrop, the Transportation Climate Initiative (TCI)—a coalition of 12 states and the District of Columbia coordinating transportation emissions reductions—is planning a cap-and-invest program. This will involve capping transportation carbon emissions and investing emissions allowance revenues in transportation modernization. Investments in public transit, electric vehicles, and pedestrian friendly streets are expected to account for a large portion of the program’s emissions reductions.

For state agencies to plan those investments, revenue from the program needs to be predictable, but an emissions cap (especially one set under the current uncertain circumstances) could yield allowance prices and revenues that are higher or lower than expected. How can TCI guarantee stable allowance revenue in the face of these uncertainties? In a new issue brief coauthored with RFF Research Assistant Derek Wietelman, we propose that the supply of allowances in the trading program be made responsive to the allowance price by introducing an “allowance supply staircase” that makes allowances available at multiple price steps.

Several features in an emissions market can help stabilize allowance prices and cap-and-trade revenue, even in the face of uncertainty. These include banking emissions allowances, expanding the market geographically, linking with other markets, and using offsets. The investment of auction revenues to achieve program-related goals also helps moderate prices. The most straightforward way to stabilize prices and revenues, however, would be to tether emissions allowance supply to allowance prices. This is common in conventional commodity markets; for example, when corn prices fall, farmers substitute to other crops to stabilize the price. Incorporating this feature would enable environmental markets to emulate the efficiency of commodity markets.

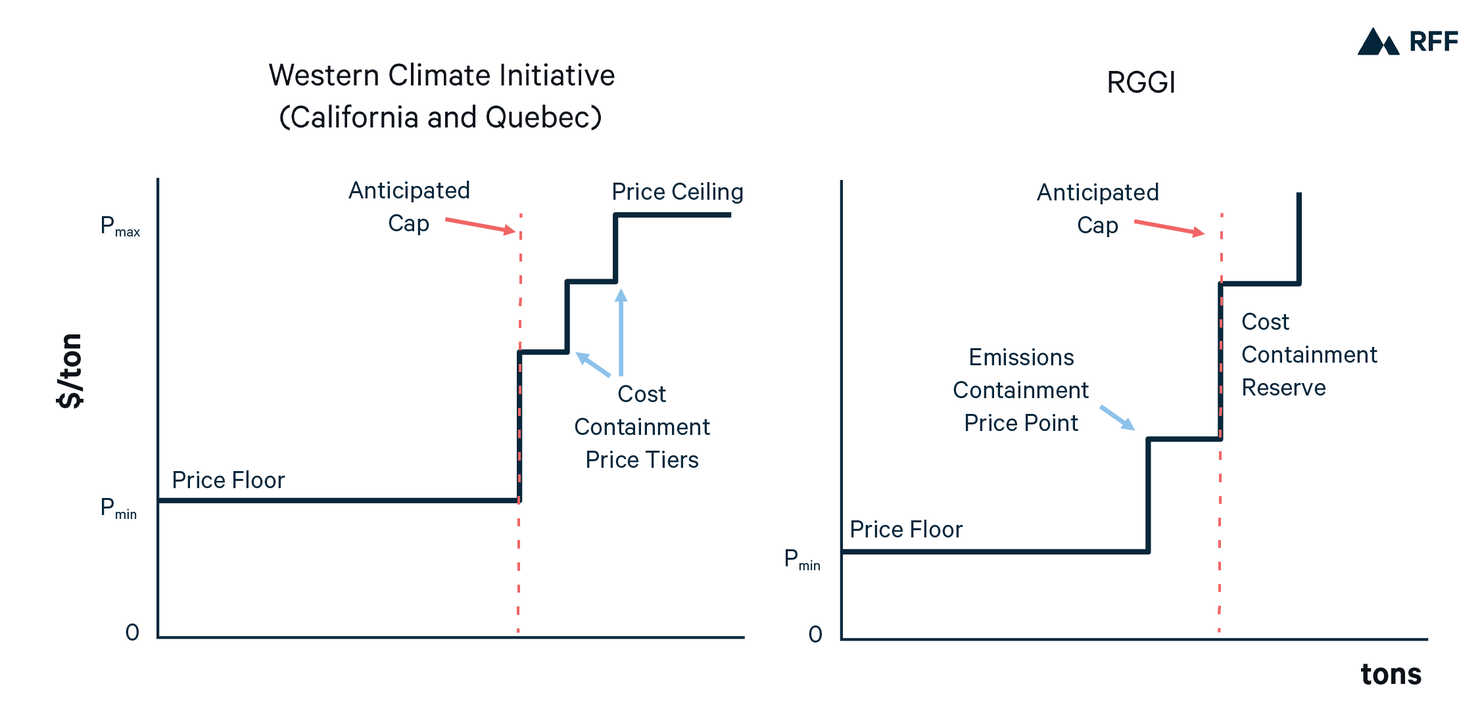

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) and Western Climate Initiative (WCI) were the first environmental markets to include price-responsive allowance supply. Instead of all allowances under the emissions cap entering the market regardless of price, RGGI and WCI have modified their emissions caps to include price steps at which allowances are gradually added to the market. RGGI was the first emissions market to include a price floor—a minimum price below which no emissions allowances could be sold. It then added a cost containment reserve—a trigger price at which additional allowances (10 percent above the cap) would be made available for sale. Starting in 2021, RGGI will add an additional price step called the emissions containment reserve, below which only 90 percent of allowances in the cap will be available. WCI currently has a price floor and three cost-containment steps that make additional allowances available at higher prices. Also in 2021, WCI will adjust the top step to create a price ceiling at which an unlimited supply of allowances become available, as Figure 1 makes clear.

Figure 1: Supply of Emissions Allowances in North American Carbon Trading Programs in 2021

RGGI and WCI use price steps to increase program stringency when emissions reductions are inexpensive or to avoid prices that policymakers consider too high for households and businesses. But price steps also have a role to play in stabilizing revenue. As can be seen in Figure 2, with a simple emissions cap, if demand for allowances winds up being higher (DH) or lower (DL) than expected (E[D]), the revenue collected will vary dramatically. With the inclusion of emissions and cost containment reserves, if demand for emissions allowances deviates from expectations, the allowance price and program revenue will vary less. Under most conditions, as the number of price steps increases, the collected revenue is more stable across a wide variety of possible levels of demand.

Figure 2: Variability of allowance prices (PL, E[P], PH) and revenue (E[R], R1, R2, R3) under three allowance supply schedules and three demand profiles (DL, E[D], DH)

The size and shape of the price steps must ultimately be decided by the TCI jurisdictions. Because transportation demand is inelastic, program revenue would be most stable if the allowance prices were fixed, as they would be under an emissions tax. In that case, small changes in demand wouldn’t change prices, but rather only change the number of allowances purchased. An emissions tax doesn’t guarantee emissions reductions the way a cap would, and reducing emissions is the main objective of TCI. But stable program revenue matters, too. By contributing to investment planning, stable program revenue helps reduce costs, which is necessary for the political sustainability of the program. Consequently, states face a trade-off between emissions and price outcomes in TCI—effectively a choice about the average slope of the emissions supply schedule. Choosing an allowance supply schedule that is neither vertical (a cap) nor horizontal (a tax) will enable TCI to balance emissions reductions and revenue predictability.

The draft Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) crafted by the TCI jurisdictions last December describes a role for emissions and cost containment reserves. The final MOU will have to define these features of the program, including the number and size of the price steps and the average slope of the allowance supply. As the coronavirus pandemic makes clear that policies need to account for future uncertainties, this aspect of program design will contribute to the durability of the program.