You might have seen the September 13, 2014, New York Times op-ed titled "Should we all take a bit of lithium?" which was the Times' 7th most emailed story of the 30 days following its publication. It came to our attention about a week after it was published, when we found a Times-reading friend squeezing an eyedropper of lithium into a glass of drinking water, without a prescription. We were concerned.

The op-ed advocated consuming trace quantities of lithium—much lower quantities than are used to treat clinical depression. The argument was that even very small amounts of lithium lift mood and promote neuron growth, so that people who consume just a little lithium will have fewer psychological problems. Others have even suggested adding lithium to the public water supply (or to soft drinks), much as we now add fluoride to drinking water to prevent tooth decay.

The Times op-ed began with a 1990 study of 27 counties in the Texas panhandle, which found that counties with more lithium in their groundwater had lower rates of suicide, homicide, and rape. It then pointed to a broad review, which found that 9 out of 11 studies (the exceptions were in England and Maryland) obtained similar results suggesting that areas with higher levels of waterborne lithium tend to have lower suicide rates and other indicators of good mental health.

As professors with expertise in water and public health, we view this type of evidence skeptically. The finding that suicide rates are lower in high-lithium counties doesn’t necessarily imply that trace quantities of lithium prevent suicide. It could instead mean that high-lithium counties happen to have other characteristics that are associated with low levels of suicide. As acknowledged by the academic review (p. 812), one “major risk in [these] studies is confounding bias.” Lithium could be confounded with some other protective factor, and if it is, then the results of the lithium studies could be biased. The list of potentially confounding influences on county suicide rates is long. Since 1897 research has associated suicide rates with demographic and social characteristics including age, religion, education, and social isolation—and there are surely other influences on suicide that we don’t even know about. Studies of suicide and waterborne lithium have typically controlled for only a handful of known confounders. Some studies haven’t controlled for confounders at all.

We were also bothered by the failures to replicate the basic result in England and Maryland. While it is easy to dismiss a single publication for one reason or other, the published literature may be just the tip of the iceberg. It may be that other researchers failed to find an association between suicide and lithium in drinking water, but did not publish the result, or reported their results selectively. This happens all the time. Researchers who fail to find what they expect are less likely to seek publication, and when researchers do try to publish disappointing results, journals are less likely to accept their work.

We decided to try and replicate the results ourselves. As it happens, the US Geological Survey (USGS) has collected data on groundwater lithium in 936 wells in 217 counties in 29 states. We linked that data to county suicide rates, which are monitored by the CDC. (There are several different versions of the CDC suicide rates; we used the version that is “smoothed” and “age-adjusted” to compensate for the fact that some counties have older or younger residents than others.)

We started with our home state of Texas. The USGS data include groundwater lithium levels for 23 Texas counties, all in the panhandle, which we assume are approximately the same as the 27 Texas panhandle counties where that 1990 study, mentioned in the Times op-ed, found that counties with more groundwater lithium had less suicide.

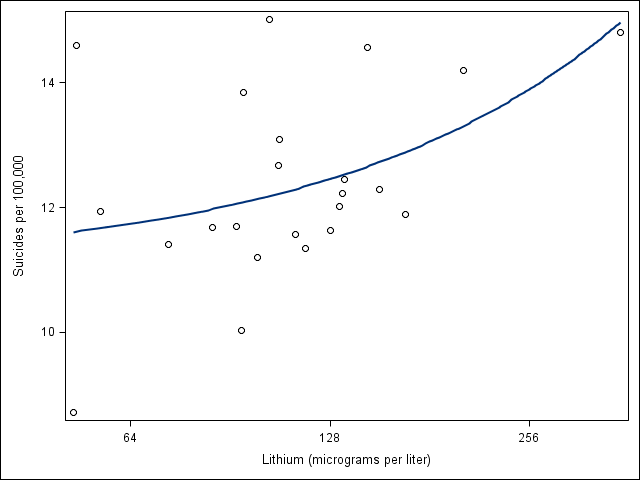

But here is what those Texas panhandle counties look like today.

The association has reversed. In 1990 it was negative—more groundwater lithium, less suicide. But today the association is positive—more lithium, more suicide. Using modern data, we can’t replicate one of the earliest and best-known results on suicide and waterborne lithium.

What happened to change the pattern? Well, 24 years have passed. Groundwater lithium changes very slowly—it comes from ancient rocks in the aquifers—but the population of the Texas panhandle has changed a bit in a quarter-century, and the parts of the population most prone to suicide may have shifted from low-lithium to high-lithium counties.

Also, the sample is rather small—4 million people but only 23 counties—and in small samples a few counties can exert undue influence on the results. Let’s see what happens if we delete just 4 counties—one from the lower left and 3 from the upper right. Without those 4 counties the relationship turns from positive to slightly negative.

So what should we do—add lithium to our water because 19 Texas counties suggest the relationship between suicide and waterborne lithium is negative? Or filter lithium out of our water because 23 Texas counties suggest the relationship is positive? Clearly we can’t make environmental and public health decisions on the basis of such shaky evidence.

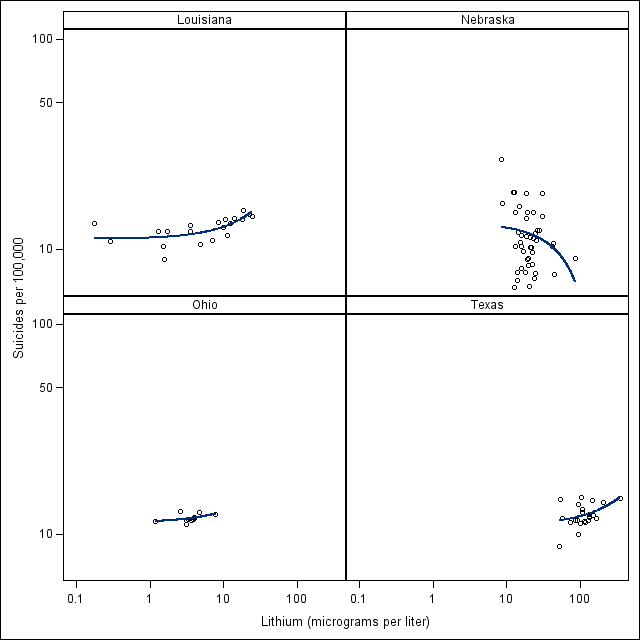

Deleting a few counties from a graph may seem a little artificial. But we don’t have to do that to see the results shift around. We’ve already seen that the pattern in the Texas panhandle is different today than it was in 1990. And it turns out it’s different in Texas than it is in other states. Here are the findings for the four states with the most USGS data on groundwater lithium: Nebraska (44 counties), Louisiana (20 counties), Ohio (13 counties), and Texas again (23 counties).

The results are all over the place. In Nebraska the association is negative—more lithium, less suicide. But in Texas and Louisiana the association is positive—more lithium, more suicide. And in Ohio there’s basically no association at all.

Are these samples just too small? Well, let’s combine the data across all 212 counties, in 29 states, with both USGS data on groundwater lithium and CDC data on suicide rates. This gives us the second-largest sample that has ever been assembled on suicide and groundwater lithium, just a little smaller than a recent study of all 226 counties in Texas. That Texas study found a negative association between waterborne lithium and suicide.

But we don’t.

In the graph above, each county is labeled with its state. There’s no association at all between lithium and suicide until we get to the counties with the highest lithium levels, mostly in Texas, and there, again, the association is positive—more lithium, more suicide.

Does this mean that high levels of waterborne lithium cause suicide? No. It means that we simply can’t infer the causal effect of waterborne lithium from the available evidence. We see different-shaped curves in different places and times, and there’s usually a lot of scatter around the curve, reminding us that other factors influence county suicide rates and could be confounding our results. The effect of groundwater lithium, if there is one, gets lost in the mix.

That doesn’t mean that these kinds of studies can never provide more convincing evidence. If the curves were steeper, with little scatter, and if they had the same shape in every time and place, then we would be less skeptical. It would be more convincing if counties saw their suicide rates spike when they switched from high-lithium groundwater to low-lithium water from lakes and streams. But the proper response to such evidence would be a clinical trial. It wouldn’t be mass medication of the water supply.

While prescription doses of lithium clearly have effects on depression, as well as side effects, at the moment we know very little about the effects of trace quantities of lithium in drinking water. If you’re depressed, there are several steps you can take that have a much stronger basis in evidence. Exercise; call a friend; do things you enjoy; get a prescription; do cognitive behavioral therapy.

Meanwhile, our friend has been adding lithium to her drinking water for three weeks now, and says she feels great. But she’s not sure why. It could be the cool fall weather.