The first Earth Day was massively influential, leading to the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, spurring the creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency, and demonstrating that the general public had begun mobilizing around environmental protection in unprecedented ways. During those first rallies in 1970 and in the years since, Earth Day also has served as inspiration for researchers who have contributed to our understanding of the environment, the economy, and the effects of humans on the natural world.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, we at Resources magazine reached out to RFF researchers and board members to ask about how Earth Day has shaped their careers and how concerns over the well-being of the environment may still animate their research.

Ann M. Bartuska, Senior Advisor

During my 30-year-plus career in the federal government and with two environmental nongovernment organizations, I often had to shift gears among issues. It was my training as an ecosystem ecologist that was largely the foundation for my ability to respond to changes, and it was likely the first Earth Day that set me on that path.

I was a sixteen-year-old who skipped school and became inspired for life, even though I had never heard of “ecology.” When I discovered the discipline as an undergraduate, it was like a light went on.

Ecology enabled me to understand the interconnections of plants, animals, soil, geology, and water. It was because of the impacts of coal mine waste on the environment that I chose a career outside academia after my PhD.

Once I began my federal government career, the issues that I dealt with read like a who’s who of an environmental textbook: acid rain, ozone exposure, ecosystem management, invasive species, sustainable forestry, climate change adaptation and mitigation, and others. I did not work on these topics as a researcher, but rather at the science-policy interface, and this is where being an ecosystem ecologist paid dividends.

Tim Brennan, Senior Fellow

An advantage of growing up around DC (Bowie High, ’70) is that it was easy to go to the big mass demonstrations of the time—including the first Earth Day, which I attended at the Washington Monument grounds on April 22, 1970.

I don't remember a lot about the event, and any influence it had on my career was highly indirect, since I didn't get into economics until my second year of grad school and spent much of my career doing antitrust and utility regulation. However, somewhere along the way, I got interested in the idea that the market failure resulting in environmental harms wasn't Big Bad Guys hurting Innocent Little People, but the inability of both sides to work it out. That idea influenced (and influences) much of my work in antitrust. And, as I’ve gotten more involved in energy and environmental policy, it has led me to conclude that there is a persistent need to be clear about exactly why markets can’t solve some problems (if problems exist at all).

Susan F. Tierney, Chair, RFF Board

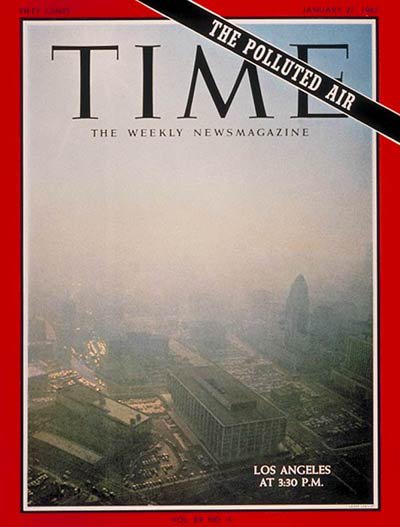

I grew up in Southern California, in the shadow of the 11,500-foot Greyback Mountain. I love mountains and hated that I couldn’t see them for much of the year; the smog was terrible. I was in my first year in college on the first Earth Day, and on that day, the mountains were nowhere to be seen. I took an interest in understanding why the air was so polluted. I learned that it was the mountains that trapped the smog, but it was the patterns of land use development, a vast network of freeways, a car culture, and so many other social systems that really caused it.

This began a lifelong interest of mine in understanding and working on environmental and energy problems that arise from a combination of public policy, economics, technology, law, finance, politics, and human behavior. If something is out of whack in one of those systems—for example, if we don’t reflect the risks of climate change in financial systems, or the cost of pollution in energy markets—then it’s no wonder that our society has developed in ways that emit enormous quantities of greenhouse gases.

Over these many decades since that first Earth Day, I have been lucky to have worked on these issues in government, academia, consulting, NGOs, and philanthropic organizations. And last year, when I went to my hometown for my 50th high school reunion, I could see Old Greyback.

Dallas Burtraw, Darius Gaskins Senior Fellow

I was 11 years old, playing flag football in a coastal San Diego town, when the official blew the whistle to stop play for five minutes. It was sort of like a water break, but it was an oxygen break. In the 1960s, during the Santa Ana winds, air pollution would come down the coast from Orange County. Playing outside, the smog felt like fingernails in one’s lungs.

Around that time, California began a sustained effort to arrest air pollution using all the tools available. This was made possible—and in fact led—by economic interests in what was known as the most conservative county in America—Orange County, home of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan—where the descent of the “Orange Curtain” was destroying the environmental amenities that made California special. I witnessed that the modern environmental movement took off running on bipartisan legs. I subsequently learned that the movement is sustained by building new economic interests like, for example, finding more jobs in protecting the environment than in destroying it.

Margaret A. Walls, Senior Fellow

I was always an outdoorsy kid and, once I reached my teen years, I became pretty passionate about environmental issues. I grew up in Kentucky on the Ohio River. For as long as I can remember, there was a coal-fired power plant downwind from my hometown. When I was in high school, a new one was proposed upwind. Everyone in town knew pollution from that plant would land right on us. This was 1977, well before the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, and those plants were dirty. As editor of my high school newspaper, I wrote an impassioned editorial arguing against the plant. In church the Sunday after the paper came out, the father of one of my friends came up to me and said, “You shouldn’t write articles like that; that plant will provide a lot of jobs for this town.” I was mortified, of course. But this was my first encounter with “jobs versus the environment”—the same narrative you hear today! My editorial didn’t have any impact, the plant was built, and the pollution in my hometown was bad as a result. I think becoming an environmental economist helped me find my sweet spot—I could work on the environmental issues I cared about, but using tools and methods that helped find solutions.

Richard D. Morgenstern, Senior Fellow

Earth Day in 1970 brought to the fore awareness of pollution at a time when the scientific understandings of the risks to human health and the environment were in their infancy. As a city boy from New York, I grew up with limited awareness of the importance of the physical environment. One of my few direct experiences with the natural world came from early morning adventures with my best friend and his dad, where we would head to Sheepshead Bay, in search of the elusive but fierce bluefish that sometimes took the bait.

The occasion of Earth Day riveted global attention to the solitary nature of this planet. Like many of my generation, I began to understand the profound interconnections between how energy was generated and the pollution that affected how many fish might flourish or not. I began to appreciate that downwind or downriver activities ultimately affect everyone: We all live downwind. Over the subsequent five decades since that first worldwide call, the growth in knowledge in the fields of environmental toxicology, epidemiology, biology, chemistry, engineering, and economics has been exponential. I was fortunate to have completed graduate school in 1970 and to have begun practicing environmental and energy economics in the mid-70s at the Congressional Budget Office, at a time when the environment was clearly a bipartisan issue.

While there has long been a broadly shared agreement about the need to protect the environment, from the outset there were profound disputes about the best policies to achieve those goals. Discerning options for policies and figuring out the costs put economics at the center of many important discussions, ranging from how clean is clean to how best to reduce greenhouse gases.

Devising ways to evaluate and quantify the risks of environmental pollution and the costs and benefits of control remain the driving concerns of my professional life. For two decades, I worked at EPA at a time when the agency got lead out of gasoline, sulfur out of smokestacks, ozone-depleting CFCs out of refrigerators, and had also begun the ongoing process of identifying and evaluating policies to reduce greenhouse gases. During those years I developed a keen appreciation for the tightrope that must be walked in devising effective policies that protect the environment and the economy. My work on those issues has flourished over the last two decades here at RFF.

At this juncture amidst a global pandemic, there is a growing appreciation of the fact that environmental factors may be an important part of the story, as studies now indicate that those regions with the worst air pollution have also experienced the worst prevalence and virulence of the disease. How does this relate to the granddaddy of environmental problems, climate change?

One must hope that massive human loss and adverse economic impacts will not be required to spur a serious response to the atmospheric build-up of greenhouse gases. The fact that the damages from climate change are expected to come over decades and to be diffused over time and space, makes it difficult for individuals to understand the true risks. Going forward, the challenge for society is to craft credible, cost-effective policies that can lessen the harms from climate change and find acceptance in the body politic—both domestically and globally. Inevitably, appropriate responses to climate change will require less traditional regulation and greater focus on the incentives to spur innovation and inspire creative talents across the globe to develop low carbon economies.

Rebecca Epanchin-Niell, Senior Fellow

Earth Day, fifty years ago, symbolized an awakening to the recognition of our incredible influence on the environment. As a species, we have an unbelievable capability to affect the earth’s processes and conditions, at local to global scales—from the chemical composition of the atmosphere and oceans, to the frequency of storms, to the composition and structure of ecosystems, and the survival of other species. We also remain very much part of the earth’s ecosystems and subject to their dynamics, from storm events to pandemics, while depending on the earth’s resources and processes for our sustenance and well-being.

I was not yet born when the first Earth Day took place, and it seems quite incredible to me to imagine a time when such a sense of recognition and responsibility had emerged about society’s impact on the environment and its value to us—a time when environmental protection was viewed as a national, rather than partisan, interest and responsibility.

I worry that the environmental protections put in place by such past actions are now taken for granted by many who have not experienced the conditions that would prevail without these laws. How many more species would we have lost? What would our air and water quality be like? How much worse would environmental inequity be?

However, we have much further to go as we seek solutions to limiting global climate change and as we help communities and ecosystems adapt. Earth Day serves as a rallying point to engage people, communities, leaders, and organizations across the globe and promote awareness among our youth, and efforts toward solutions and action must be sustained to foster needed changes. Outcomes depend on the collective choices made by each of us—big and small, and as individuals to nations.