The federal review process for solar projects crucially protects environmental and cultural resources, but reforms can help minimize delays.

As the United States works to decarbonize the power sector, one trend is clear: solar power will play a growing role in US electricity generation. The amount of electricity generated from solar power has grown rapidly as costs have plunged by 90 percent since 2009. Recent projections from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) show that as much as half of new generation resources that come online through 2050 could be powered by the sun.

But while costs have dropped, other barriers to new solar generation remain. One of these impediments is the series of permits and permissions that solar projects must obtain from the federal government before facilities can be built. The federal review process for large solar projects provides a critical filter to ensure that projects won’t harm ecosystems or land with cultural importance; such a lengthy process also can slow progress toward climate change mitigation goals. Fortunately, improvements to the permitting process can be made to avoid unnecessary slowdowns.

My new study—conducted with Louisiana State University’s Valkyrie Buffa and Lindsay Rich—describes how a sample of real-world solar projects have navigated federal permitting processes, from the drawing board to actually breaking ground. Specifically, we examine the effects of the federal solar permitting process on 45 utility-scale solar projects from 2008 to 2019. Our goal was to identify what obstacles these kinds of projects face in the way of federal permitting and review processes, and how these processes could be streamlined in the future without sacrificing effectiveness.

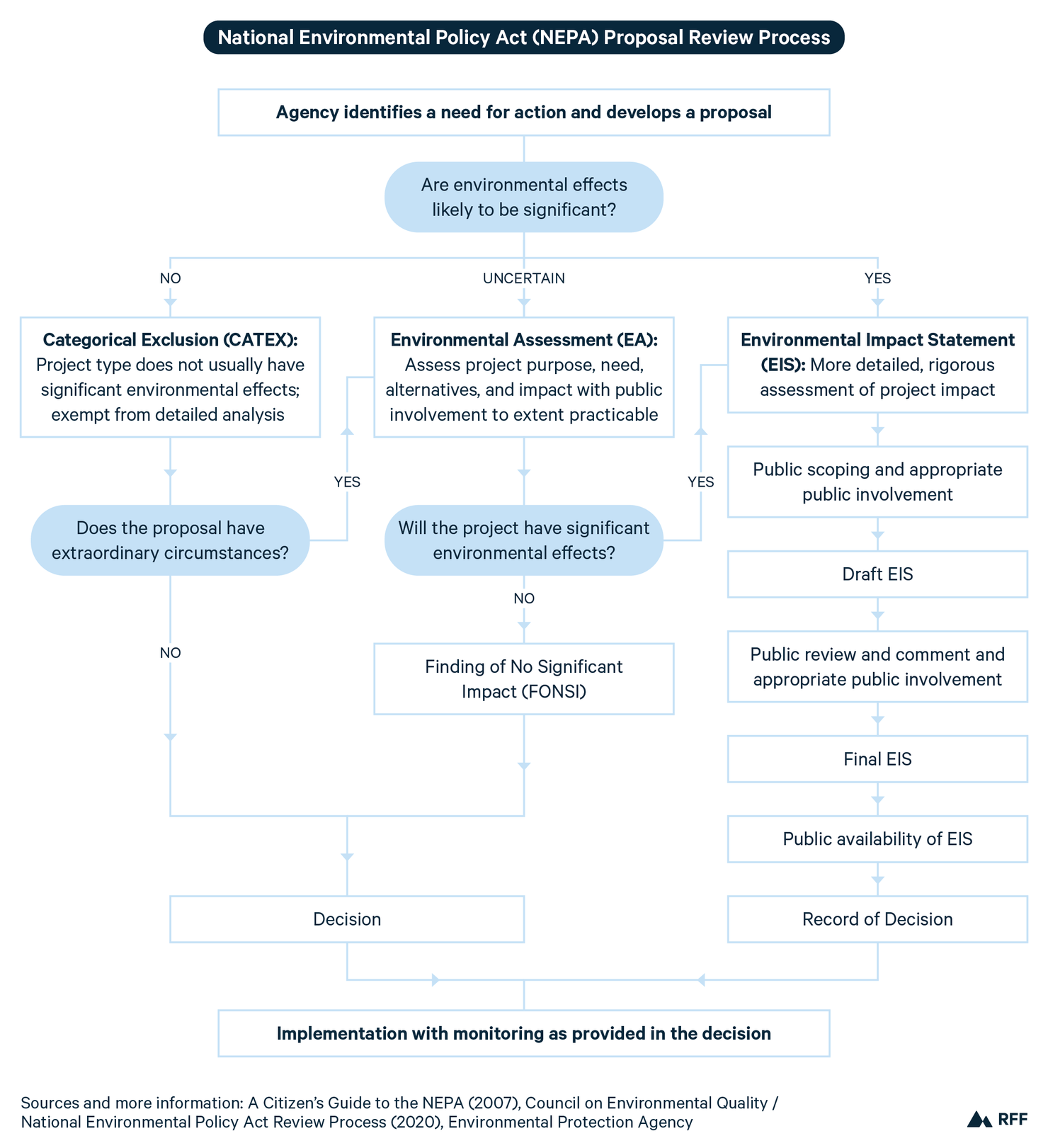

From 45 initial projects, the paper takes a closer look at a subset of 20 utility-scale solar projects that required more substantive reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). For 11 projects that needed to provide an environmental impact statement because of NEPA guidelines, the review process alone took one to two years. The remaining nine projects required roughly six to nine months to complete an environmental assessment—which is a less rigorous process than an environmental impact statement—with a finding of “No Significant Impact.” Many of the projects required permits from several agencies, such as the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Army Corps of Engineers.

Our paper lays out the permitting processes required for solar projects on federal, state, tribal, and private lands—processes which assess both the environmental impacts and the effects of the project on culturally significant sites. Figure 1 lists the federal permitting and review requirements in place to protect water resources, federally listed plant and animal species, and cultural resources. Projects planned for federal lands also must obtain a separate approval from the federal land management agencies.

Figure 1. National Environmental Policy Act Proposal Review Process

One step that can be taken to reduce delays due to the permitting process would be to determine ahead of time where new projects can be built with minimal cultural and environmental impact. For example, if the Bureau of Land Management identifies additional solar energy zones (SEZs) that are seen as favorable for solar development, more projects may benefit from expedited review processes. This is particularly true if the new SEZs are in different areas than existing SEZs, allowing for a greater geographic dispersal in siting these projects.

Our new paper offers several suggestions for improving the current federal permitting process, including:

- Proactively identify land where solar farms would have minimal negative impacts. Federal agencies could speed up the review process by identifying areas where utility-scale solar energy plants would have minimal impact on the environment.

- Utilize Superfund and brownfield sites for renewable energy development. Not only does encouraging renewable energy on these sites return impaired land to productive use, but the sites are attractive because a solar farm is unlikely to have further adverse environmental effects. Of the 45 projects in our case study, 4 are located on Superfund sites.

Most of the projects we cover in this study began the federal approval process before 2015. In future work, we plan to add projects initiated and approved over the last five years. In addition, we plan to delve deeper into the seven solar projects that offer some intersection with federal government agencies outside the NEPA process.

The review processes in place for solar projects are important for protecting environmental and cultural resources, but they nevertheless can be implemented more expeditiously. To make the ambitious climate goals of the Biden administration a reality, building more solar energy projects is imperative, and the reforms we’ve outlined in our paper can help.