The future of fossil fuels is a polarizing issue around the world. On one end of the issue, people want to put an end to fossil fuel use in a decade, while the other end denies climate change and wants to pursue business as usual practices. Neither side has realistic goals.

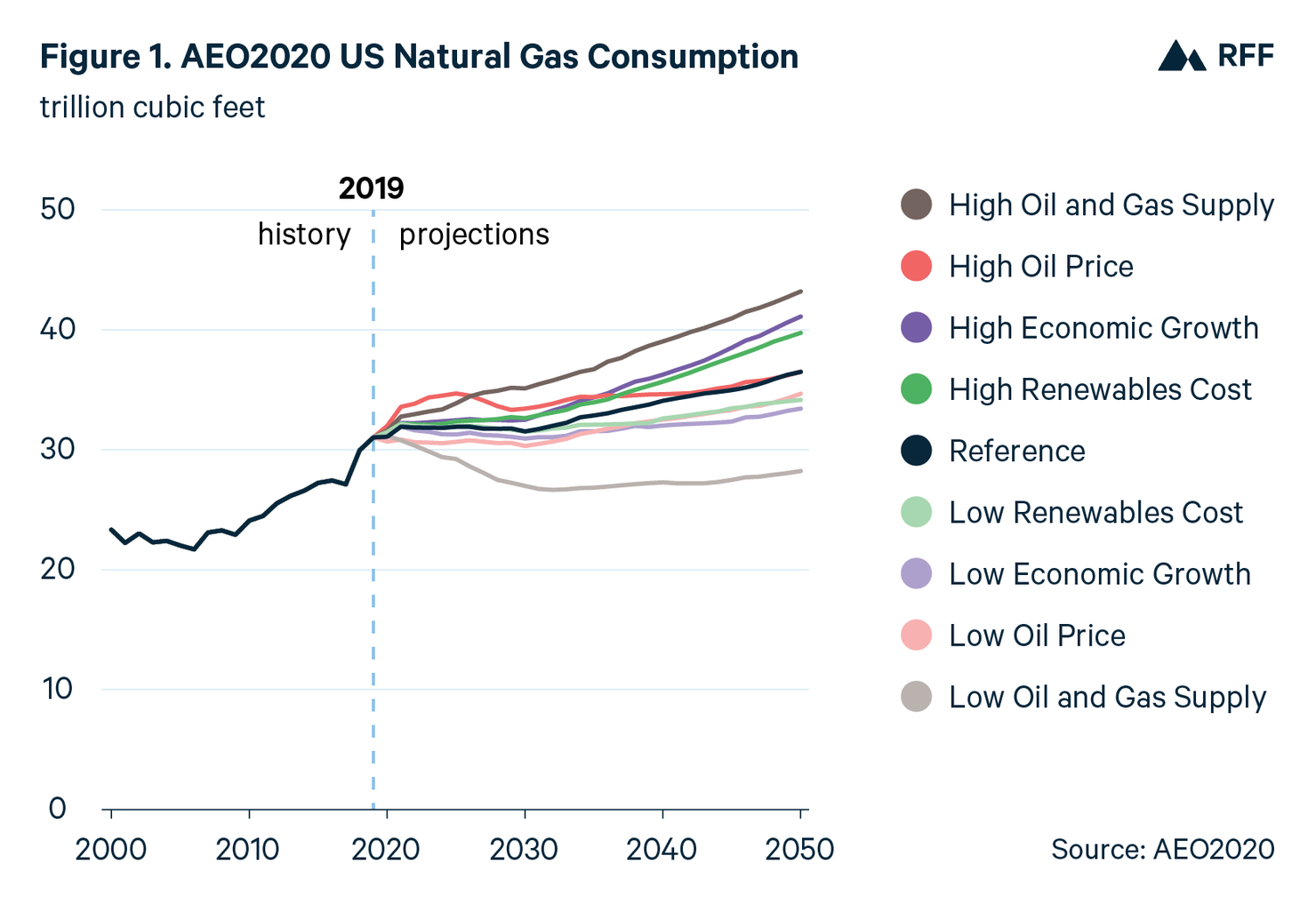

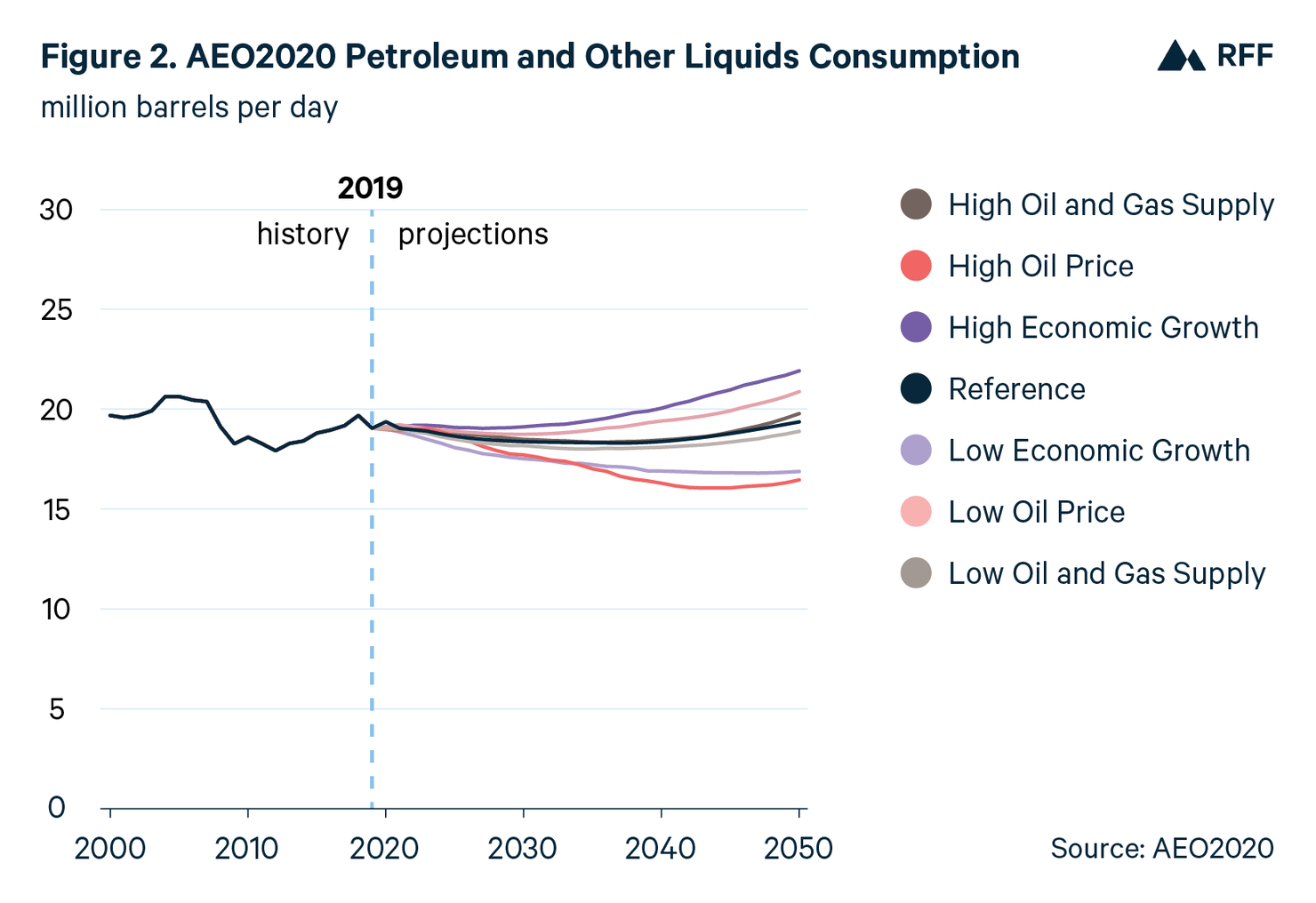

Analysts around the world predict that we will remain dependent on fossil fuels well into midcentury. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts for most of its scenarios in its 2020 Annual Energy Outlook that US natural gas consumption will continue at above current levels through 2050 for all but one scenario (Figure 1). It also predicts that US oil consumption could decline as much as, but no more than, 25 percent, and could increase (Figure 2). Granted, none of these scenarios include a carbon tax or other major greenhouse gas reduction policies. In a side case with a $35-per-ton CO₂ tax, EIA estimates that natural gas use declines from generating 2,000 billion kilowatt-hours (BkWh) to 1,300 BkWh in 2050 (although renewables generate over 3,000 BkWh). Internationally, with so much growth expected in the demand for electricity, the International Energy Agency sees continued heavy global reliance on natural gas, even as renewables and biogas eat into the market share of natural gas.

The vast middle ground between the extremes allows for more than one strategy to operate at the same time: policies and technologies can be implemented to reduce demand for fossil fuels and to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel production, transport, and use. With coal on its way out of the US energy mix, natural gas and renewables have been replacing it in power generation, although natural gas has yet to make inroads against oil as a transport fuel. While demand for natural gas-generated power could be reduced through policy actions, the more viable option for deep decarbonization may well be carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS).

In addition, the methane emissions from the natural gas life cycle (a powerful greenhouse gas) add to concerns about the fuel’s global warming footprint, irrespective of how much CO₂ is captured when the gas is burned for power. Here, there is much cause for optimism. In spite of actions by the Trump administration to weaken or eliminate methane regulations, the oil and gas industry is subject to methane-reducing regulations in several states and is subject to a variety of forces (some self-generated) to obtain further reductions, such as the following:

- efforts by the American Gas Association and Edison Electric Institute to set methane intensity standards that reflect emissions from the sector more accurately than those reported to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program

- voluntary efforts to put limits on methane emissions, including the ONE Future coalition’s one percent methane intensity standard over the natural gas life cycle, the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative’s similar standard (mostly a European effort), Cheniere’s plan to help its gas suppliers develop low-methane gas, and EPA’s Methane Challenge Program

- development of protocols for rating company performance in greening its gas (e.g. Trustwell)

- a few binary trades between producers of low-methane-intensity natural gas and other companies that want it

- pressure from stakeholders on the European Commission to adopt requirements that natural gas imports to Europe be certified as having low-methane emissions

- congressional bills that could help create a demand for certified low-methane-emissions natural gas, by giving low-methane natural gas extra credit compared to regular natural gas in a tradable clean energy standard policy

- several efforts (by us at RFF and the Rocky Mountain Institute) to help develop design ideas or (in the case of Platt’s) actual markets in low-methane-intensity natural gas; market creation would be aided by the creation of digital platforms to facilitate rapid and frequent trades, which are in development by a number of companies.

Our recent webinar to highlight RFF’s work on this topic focused on a number of issues to be solved before a viable market can be created. These issues fall into four categories: economic, certification, technical design, and governance.

An important economic issue is how large and strong the demand for low-methane-intensity natural gas might be. There might be intense demand for a small amount of production, intense demand for a large amount of production, or maybe almost no demand at all. As yet, no one knows—although as noted, legislation in the works and other initiatives could reveal and boost demand. A related issue is how large the premium might be. The answer to this question depends on the interaction between the costs of producing green gas and the willingness to pay for it. While a few trades have happened already, the premiums paid have not been made public.

A central certification issue is how costly this system will be. How frequently will the gas need to be certified, and how will the evidence be communicated to potential buyers?

Of the myriad technical design issues, the hardest is measuring actual performance against whatever standard is set for superior performance. Monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems are still not fully developed, and no one has yet figured out how to reliably identify “super emitters,” which are responsible for a high proportion of total methane emissions. Buyers will need assurances that the green gas they buy is truly as green as advertised, and the super emitter problem is being handled.

As for governance, we believe that industry could develop a market quickly, based on voluntary participants, and with limited government participation. But this strategy may be a hard sell to some buyers.

While many issues still need some work before a market in low-methane-intensity natural gas is operational, all the aforementioned activities to reduce methane emissions contribute components to the market. The benchmarks set by several initiatives provide a starting place for defining superior performance, and the efforts to better measure methane intensity will permit superior performers to be identified. If a clean energy standard bill passed or the European Commission adopted a low-methane import requirement, these would spur the development of certification and audit infrastructure, and simultaneously create a strong demand for and potentially high premium on such gas.

Ultimately, as the American public becomes more educated about the perils of methane emissions for the climate and the ability of markets to pay the oil and gas sector to reduce those emissions, pressure on power companies, gas distribution companies, and major industrial buyers will grow. Pairing very low methane emissions over the life cycle of natural gas with major advances in carbon capture, utilization, and storage would largely decarbonize the natural gas sector—which is a much better option than keeping a valuable and inexpensive resource in the ground.