The Clean Electricity Performance Program, which would require utilities to increase their share of clean electricity by 4 percent annually, could feature in the reconciliation bill. Evidence from US states suggests that the ambitious program could be feasible and spur additional investment in renewables.

Democrats’ massive budget reconciliation bill, which the House of Representatives is preparing to pass and the Senate is also grappling with, prioritizes climate action by dedicating funds to advancing clean energy deployment in the electricity and transportation sectors. Among the provisions expected to feature in the final legislation is $150 billion for the Clean Electricity Performance Program (CEPP), which could set the United States on course to transform the electricity sector in the coming decades.

As currently designed, the CEPP, which is similar to a clean electricity standard, requires electricity suppliers to increase their share of clean electricity by 4 percent annually. If suppliers meet the 4 percent goal, then they are eligible to receive a grant of $150 for every megawatt-hour that they supply over the threshold of the previous year’s share of clean generation plus 1.5 percent. If electricity suppliers don’t meet the 4 percent goal, then they must pay $40 for each megawatt-hour that they fall short. Some flexibility is built into the program, and retailers that are unable to meet the 4 percent annual goal can defer payments for up to two years.

The goals in the CEPP embody the most ambitious clean electricity policy to date at the federal level. Such an ambitious policy begs the question of the realistic achievability of the program’s targets. Is a 4 percent annual increase in clean power really feasible?

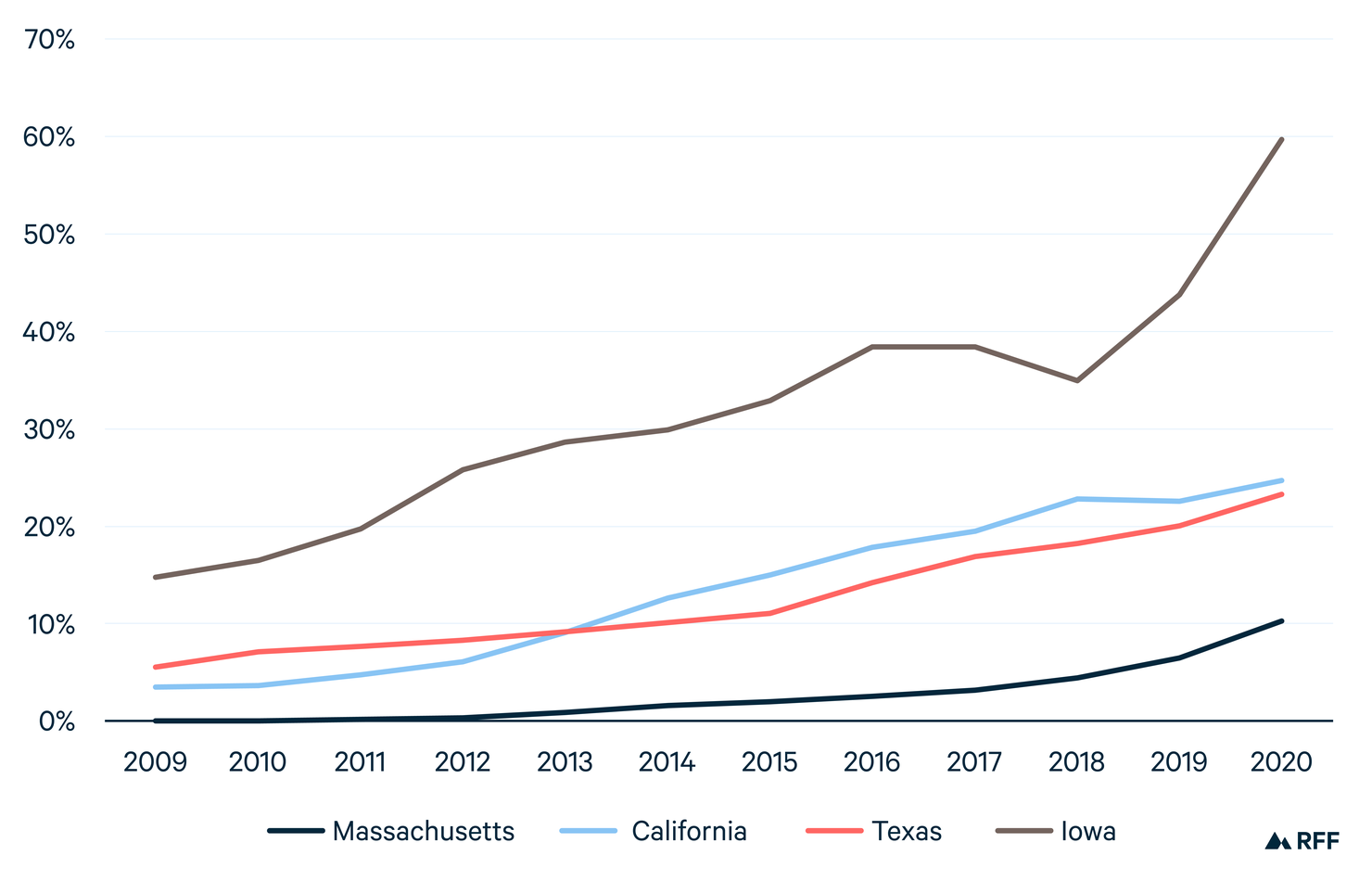

While we don’t know for sure, we do have evidence from some US states to indicate that the 4 percent level of annual clean power growth is certainly possible (Figure 1). For example, California’s many ambitious environmental policies include a cap-and-trade program; a renewable portfolio standard; and, most recently, a requirement of 100 percent clean power by 2045. With these policies in place, California’s share of clean energy generation has grown significantly over the past decade. California’s annual increase in power from solar and wind as a share of net generation has reached as high as 3.5 percent in recent years. Massachusetts, too, saw a 3.8 percent increase in generation from solar and wind from 2019 to 2020. Significant progress has been made in Iowa in particular, which saw a 15.9 percent increase in clean energy generation (mostly from wind) in just one year, from 2019 to 2020.

Figure 1. Annual Contribution of Solar and Wind as a Percentage of Net Generation

Source: US Energy Information Administration. Note that the reconciliation bill calls for an increase in the percentage of load served, which accounts for line losses (i.e., the amount of electricity lost during transmission and distribution across power lines in the grid), whereas these numbers reflect the percentage of generation without line losses. But overall, the quantities under consideration are very similar

While several factors influence the percentage of generation that renewable production makes up in a given year (including variability in solar and wind resources, but also other resources like hydropower and demand for electricity), this increasing share of net generation from solar and wind generation (much of which likely came from new investment) occurred without a strong federal policy in place. In some states, like Texas and Iowa, growth in clean energy generation occurred even without aggressive state incentives in place. In these states, projects mainly have relied on federal tax credits, such as the investment tax credit for solar and the production tax credit for wind, which have been phased down in recent years and have lapsed in the past.

With expanded support from the federal government, the scale of growth described by the CEPP certainly seems possible, especially since the reconciliation proposal from the House Committee on Energy and Commerce supports extensions for the production tax credit and investment tax credit at their full values for the next decade. That proposal also includes provisions for direct pay—meaning that renewable energy developers can reap the benefits without finding a tax equity investor, thus reducing another barrier to development.

Even if the goals of the CEPP are theoretically achievable, design questions around the program persist. For instance, how much will federal support of the CEPP help add new renewables—or will federal support fund projects that would have happened anyway? In a hearing on September 28, Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) expressed concerns in his closing remarks about the CEPP potentially “paying utilities for what they’re going to do, anyway.”

The CEPP anticipates this concern by crediting only the clean generation that exceeds the previous year’s clean generation plus 1.5 percent. At the national level, according to the US Energy Information Administration’s Electricity Data Browser, renewables have been growing by about 0.5 percent to over 2 percent annually as a share of net generation. Thus, for most states, paying utilities to reach 4 percent may not result in paying for what the suppliers would do in the absence of the policy, given that the payments only start at 1.5 percent growth, and most utilities probably do not currently meet that level of growth. However, this issue of redundancy could be a valid concern for states that consistently meet higher targets, such as Massachusetts and California.

Overall, concerns about the CEPP either being too ambitious or providing unnecessary funds may not be very worrisome. States have shown that a target of 4 percent annual growth in renewables is possible, and 4 percent growth is even more likely with the CEPP in place along with extensions for the renewable tax credits. Also, while some states are exceeding 1.5 percent annual growth (driven largely by state policy incentives), national data show that most states are not. Thus, in most cases, the CEPP likely will provide support for additional investment in renewables, rather than subsidize existing investments.