Calamitous floods this summer in eastern Kentucky highlight the importance of flood insurance in disaster recovery. However, residential flood insurance remains low in households that suffer the most. Resources for the Future scholars share insights about why and suggestions for increasing insurance uptake and improving flood resilience.

Several counties in eastern Kentucky experienced devastating flooding over the course of several days in late July this year. The floods were the result of a stationary weather front that hung over the region for several days in a row, generating very heavy rainfall over a short period of time and causing unprecedented flash flooding. Additionally, the topography of Appalachia—steep hills bisected by many streams and rivers—makes it a landscape that’s prone to flooding, with surface mining of coal worsening the problem in some areas. Meanwhile, by necessity, many homes and businesses are built in the valleys on narrow flood plains, where flooding can lead to dire consequences for individuals and families. In spite of this propensity for flooding in the area, residential flood insurance remains low for households in the Kentucky counties that have been affected the most. We set out to understand why and offer suggestions for increasing insurance uptake and improving flood resilience in these hard-hit communities.

The main flood event occurred on July 28, with President Joe Biden declaring a major disaster on July 29 that covered 13 Kentucky counties. (Five more counties were later added to the list.) Preliminary damage assessments from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) have yet to be released, but by all accounts, the event was catastrophic, destroying many homes and public buildings, washing out roads and bridges, and creating widespread power and water-system outages. Most significantly, the flooding directly led to 39 deaths and thus accounted for more than half of the total deaths from flooding so far this year in the United States.

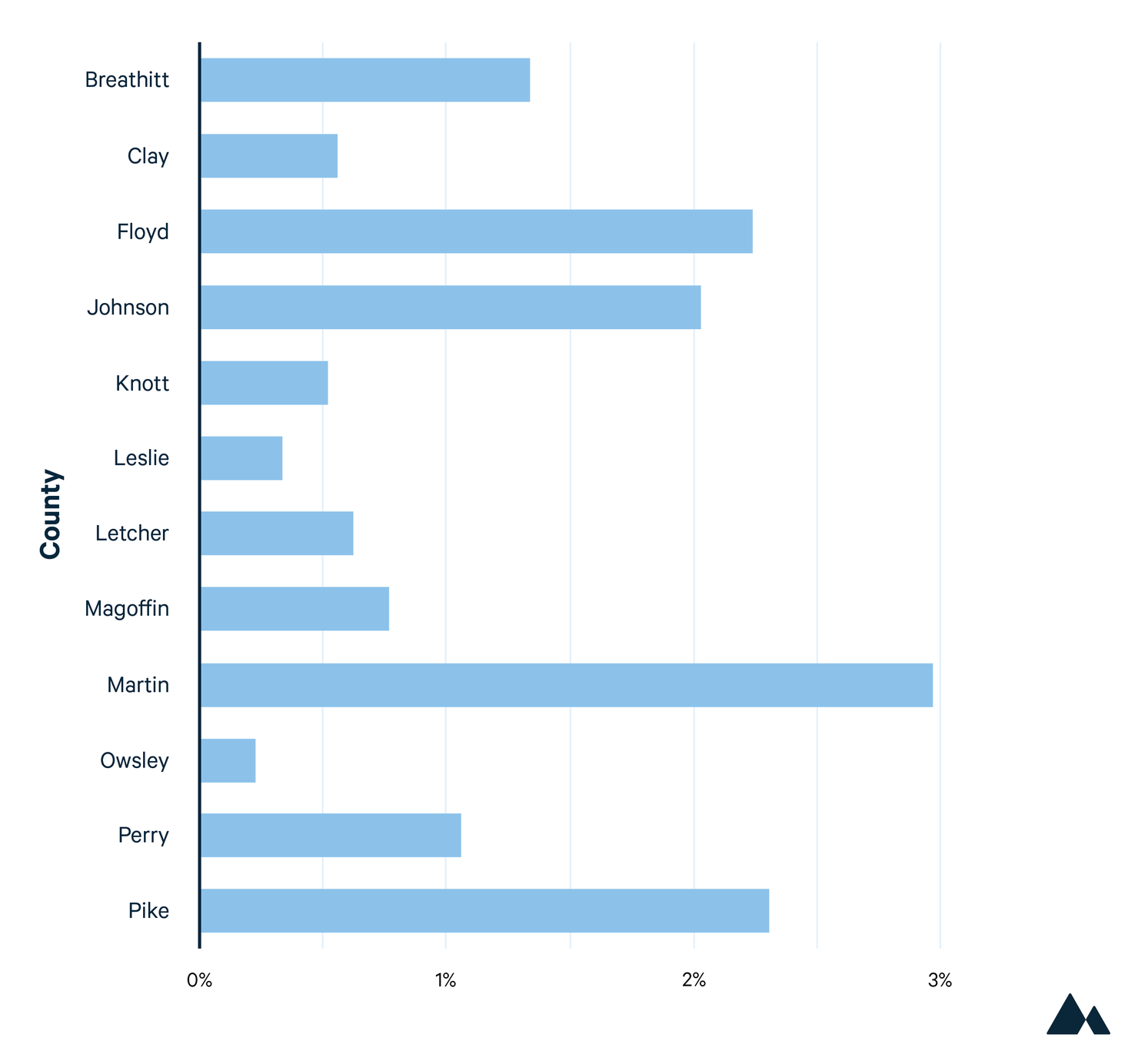

As of August 23, FEMA reported that over $60 million in aid has been provided to the region, much of it for meeting immediate emergency needs for temporary shelter and food. Whether these communities will have the financial resources needed for long-term recovery is an open question, but many factors do not bode well. Probably the main vulnerability for individual homeowners is the lack of flood insurance. Standard homeowners insurance policies do not cover property damage from flooding, but the proportion of houses in eastern Kentucky that are covered by a flood insurance policy from the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is extremely low (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percent of Housing Units Covered by a Flood Insurance Policy in the Recently Flooded Areas of Eastern Kentucky, by County

This figure shows flood insurance coverage for 12 counties in the flooded areas of Kentucky. Five more counties outside of eastern Kentucky were affected by flooding; another, Wolfe County, does not participate in the National Flood Insurance Program. Data sources: Residential flood insurance policy data from OpenFEMA Dataset: FIMA Redacted Policies. Number of housing units in each county from US Census.

On average across the 12 counties, only 1.2 percent of homes were insured for flood damage at the time the disaster struck. Without flood insurance, households with property damage need to rely on their personal savings, loans (including Small Business Administration loans), federal aid through the FEMA Individual Assistance Program, and charity. For low-income families, these non-insurance options have some limitations.

For example, low- and moderate-income families generally have little in savings. According to the Federal Reserve System’s Survey of Consumer Finances, families in the lowest-income quintile (with a median income of $16,290) have only $810 in transaction savings accounts (readily accessible checking, savings, and money market accounts). Families in the second-lowest income quintile (with a median income of $35,000) have an average savings of $2,050.

Homeowners can get a Small Business Administration loan for up to $200,000 to repair their homes, and renters can get up to $40,000. But to qualify, a borrower must have collateral and a good credit history. Many low-income individuals and families have neither. So far, only $11.3 million in Small Business Administration loans has been approved in eastern Kentucky—a small amount, given the extent of the damage.

The maximum grant available for homeowners from the FEMA Individual Assistance Program is $37,900, and most homeowners get far less than the maximum after a disaster. FEMA makes it clear that these grants are not meant to return a dwelling to its pre-storm condition; rather, the agency specifies only that it be habitable. Moreover, the Individual Assistance Program is notorious for paperwork headaches, delays, and unexpected denials of aid, all problems that arose in Kentucky this summer. By contrast, the NFIP coverage limits for buildings and personal property are $250,000 and $100,000, respectively.

Charitable donations are important in the wake of a disaster but rarely are enough to rebuild damaged properties and cover all longer-term needs. The Team Eastern Kentucky Flood Relief Fund, established by Governor Andy Beshear (D-KY) in the wake of the floods, had raised $5.2 million as of August 11, two weeks after the flood—far less than will be needed to address all damages.

Explaining the Gaps in Flood Insurance Coverage

If flood insurance is essential for post-flood recovery, why is residential flood insurance coverage so low in these Kentucky counties?

First, to be clear, coverage is low in a lot of communities in the United States. The “flood insurance gap” has been a major concern for many years. The gap is particularly large in low-income communities, and these Kentucky counties are relatively poor. The median household income for the five hardest-hit counties—Breathitt, Clay, Knott, Letcher, and Perry—is $33,150, roughly one-half the US median. The average poverty rate is 27.4 percent, 2.4 times the US average. With the average cost of an NFIP policy in Kentucky at nearly $1,200, families living paycheck to paycheck and struggling to cover other living expenses may feel like flood insurance is a luxury they cannot afford.

Second, the FEMA-designated Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA)—the area with a 1 percent probability of flooding each year (or 26 percent probability over a 30-year period)—covers only about 4 percent of the land area in these counties. The SFHA is the area where homes with federally backed mortgages are required to have flood insurance. Many property owners hard hit by the flood were outside the SFHA, and because flood insurance was not required, incorrectly assumed they were safe from flooding.

What, then, are some options to address affordability problems; increase insurance coverage; and, most importantly, build resilience to future floods in these Appalachian communities and elsewhere?

In our view, the region needs a focused effort from the federal government across multiple fronts, including (1) better communication of flood risks; (2) financial and technical assistance to access federal funding for resilience projects and hazard mitigation; and (3) financial assistance to increase insurance coverage.

FEMA should build programs that communicate flood risk to communities and property owners based on graduated risk, rather than the FEMA SFHA flood maps. The designation of SFHAs is required for the administration of the “mandatory purchase requirement” and to direct where communities must implement NFIP-defined building codes. However, property owners need to understand that FEMA maps do not report all flood risk; in other words, flood risk varies within the SFHA and is not zero outside of the SFHA. Toward that end, FEMA has initiated its Future of Flood Risk Data initiative that will report varying levels of risk. Until that initiative bears fruit, an alternative source for such information comes from First Street Foundation, an independent organization that models risks from natural hazards for individual properties across the United States. Its Flood Factor metric now is incorporated into Realtor.com property listings. According to Flood Factor, approximately 65 percent of housing units in the flooded region of eastern Kentucky were in the 1 percent flood zone, a sharp contrast to the FEMA maps. Making this, or similar, information more readily available to homeowners could better inform planning for community flood resilience and increase insurance uptake.

FEMA, in cooperation with philanthropic organizations, should offer technical assistance to local governments in Appalachia, so these communities can better compete for access to federal funding and invest in flood resilience. Federal funding programs exist in multiple agencies (including FEMA, the Army Corps of Engineers, the US Department of Agriculture, and the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement), but navigating their processes and requirements, and developing a flood resilience plan, is well beyond the capacity of most small rural communities. Own-source revenues (revenues from property taxes and other local sources but excluding intergovernmental transfers) for the 13 hardest-hit counties in eastern Kentucky averaged only $27 million in 2020. Emergency management services consist mostly of a single emergency-manager position and often no department website or other resources. If the nation is going to take a proactive approach to securing flood resilience for these rural Appalachian communities—where climate change is expected to bring increased flood risks—then a committed effort must help them access funding and provide support on implementation. These communities cannot go it alone.

Congress should accelerate efforts to support an NFIP affordability program. Even with investments to reduce flood risks, insurance remains essential for recovery from floods. If the nation is going to take a proactive approach to securing flood resilience for populations in Appalachia, Congress should direct the NFIP to offer means-tested (income-based) discounts for insurance premiums in the region and then commit to making payments from the US Department of the Treasury to offset the revenue lost by offering these discounts. This two-pronged approach would be an administratively simple way to address Congress’s concern for NFIP solvency while reducing premiums for low-income homeowners.

Additional Hurdles in Flood Resilience

Even with financial and technical assistance, two additional hurdles exist for improving resilience in rural Appalachian communities. The first is that federal funding programs are biased toward protecting higher-value properties. This bias happens because most programs rely on a benefit-cost test in which benefits are calculated based on avoided flood damages, which are higher for higher-value properties. The problem exists for investments in reducing flood hazards (such as via levees), floodproofing (such as via building elevation), and property buyouts, and results in lower-income rural areas often being at a disadvantage when competing for federal funds.

To get around this hurdle in Appalachia, several possibilities seem within reach. First, in competitions for federal funds, projects in places like eastern Kentucky should be evaluated within the regional context and not compared to areas in other parts of the United States. Second, an expanded view of what constitutes benefits, beyond simple property values, should be considered when evaluating project investments. This expanded view may mean including the numbers of people affected, weighting properties differently when calculating avoided damage, and other options. Third, distributional considerations should be incorporated into the criteria for making decisions about funding projects. The Justice40 initiative—which requires that 40 percent of the benefits of certain federal investments go to disadvantaged communities—provides an opportunity to address environmental justice concerns and could help communities like those in eastern Kentucky access more resources. In fact, the floods in eastern Kentucky may provide an important litmus test for how seriously the federal government is taking Justice40 in the context of climate resilience.

The second hurdle, which exists in many communities, concerns property buyouts. To be clear, buyouts are not appropriate for every property and neighborhood, but should be used selectively as one part of a comprehensive program. However, to ask people to move from a house or a neighborhood, in which they have strong emotional attachments and where their families may have lived for generations, is challenging. At a minimum, buyouts need to be supplemented with financial, technical, and informational assistance for relocation to ensure that people are moving toward economic opportunity and improved outcomes, including improved resilience to floods.

Longer-Term Solutions to Ensuring Access to Insurance

Experts at Resources for the Future and others have proposed a strategy of community-based insurance for low-income households. A local government could prepare for future floods in its jurisdiction by purchasing private parametric microinsurance, which is specific to lower-income households and facilitates fast and flexible funding after disasters. The payout under a parametric microinsurance policy is limited but immediate after a flood, based on a set of observable flood metrics rather than the typical, slower methods of formal damage assessment. As a result, premiums are low.

Investigating the feasibility of community insurance in Appalachia would be worthwhile, but immediate congressional action to make the NFIP premiums affordable for low-income households should be a priority.

The floods in eastern Kentucky have had serious impacts on families and communities. Moving forward, a hard look is warranted at how to improve the resilience of the region—by reducing flood risk and increasing insurance coverage—so that households will be able to survive, recover more quickly, and recover completely when the next flood event occurs.