At the end of January, the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) released their market report for the fourth quarter of 2018, showing that for the fourth straight year, annual wind project installations exceeded seven gigawatts (GW). There are a few ways to consider the significance of this headline data. First, installed wind capacity is now almost 100 GW, approaching 10 percent of total US electricity-generating capacity. Second, as a share of new capacity, wind represented nearly one-third of total capacity installed in 2016 and 2017 (for projects 1 megawatt (MW) or greater), making it the second-largest source of new MW-scale capacity after natural gas. With a jump in natural gas power installed in 2018, wind’s share of new capacity declined this past year, but it will still account for about one-fifth. Third, the AWEA report noted wind capacity that was either under construction or in advanced development totaled 35 GW, so future installations are likely to be robust, at least for the next few years.

In addition to the trends and context of total wind installations, there has been an important development in the types of wind projects installed during the past several years. In an RFF working paper, “Reducing Risk in Merchant Wind and Solar Projects through Financial Hedges,” I assess how financial hedges, which are contracts for risk mitigation, have expanded the market opportunities for wind projects.

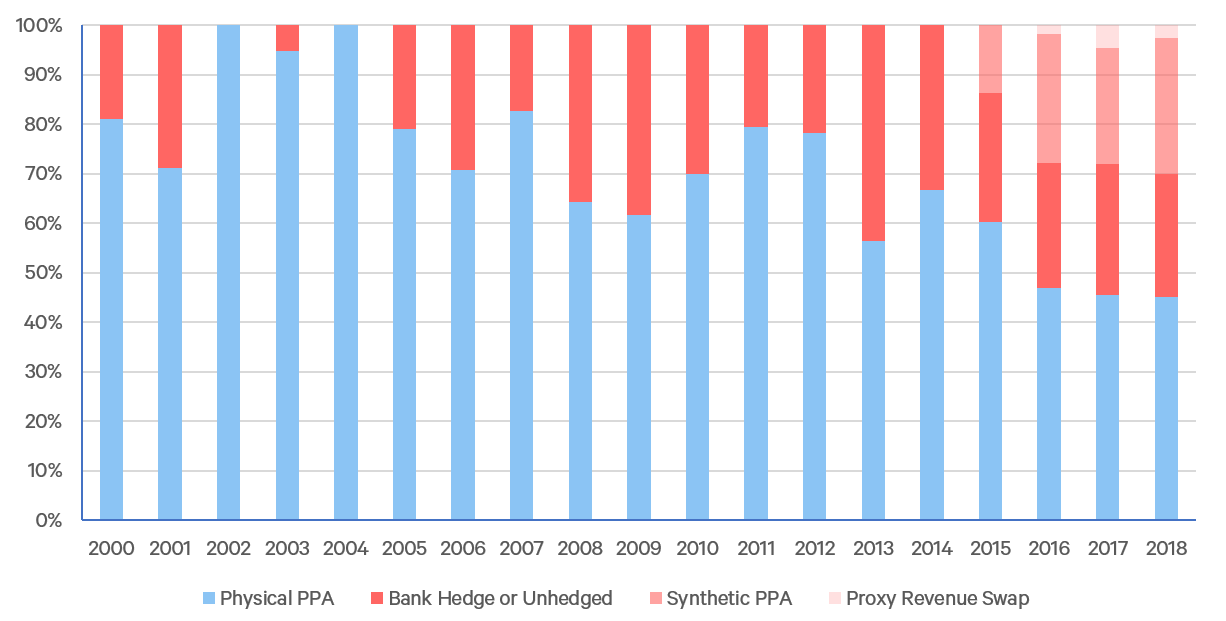

Wind projects may either enter into long-term contracts with utilities or end power users for the electricity they will generate, known as physical power purchase agreements (physical PPAs), or they may sell their electricity into wholesale markets. Power projects that sell into wholesale markets are often referred to as merchant generators, so wind installations may be categorized as contracted, merchant, or quasi-merchant (projects with both contracted and merchant portions). Figure 1 shows how the proportion of merchant or quasi-merchant projects (displayed in various shades of red) has increased over time. Although merchant designs have existed since 2000, they typically represented less than 30 percent of annual installations until the past six years. However, since 2016, merchant or quasi-merchant wind projects have accounted for about half of all new wind generating capacity. Without merchant opportunities, wind installations could have been significantly lower over the past three years.

Figure 1. Percentage of US Wind Capacity Installations, by Physical PPA or Merchant Structure

The choice of physical PPA versus merchant revenue presents wind developers with a tradeoff between risk and return. A physical PPA entails comparatively low risk for several reasons—most importantly, the project receives an agreed-upon price for every megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity it generates, and the contract lasts for close to the expected life of the project. The disadvantage of a physical PPA is that because the pool of potential customers—known as offtakers, a large majority of which are utilities or utility cooperatives—is limited, competition among wind projects has led to low PPA prices. Selling into a wholesale market instead promises a higher expected return, but the project would then face the risk of electricity price fluctuations over the life of the facility. Obtaining low-cost project financing typically requires predictability in revenues, so developers of merchant wind projects generally enter into hedging agreements to reduce their revenue risk and satisfy the demands of financiers.

Although there are several ways in which a wind project could be hedged (I review five in the working paper, but only three have been definitively used in recent years), each of them functions by swapping unpredictable revenue from the project in return for more predictable revenue from the hedging counterparty. The two most common designs, bank hedges and synthetic PPAs, are both hedges based on swapping actual electricity prices for agreed-upon fixed prices. The third design, a proxy revenue swap, hedges against both electricity price and weather (wind speed) risks. For a wind project, the key differences between these three hedges are the fixed price (or amount, in the case of a proxy revenue swap) that the project would receive, as well as the residual risks that the project would bear with the hedge in place. From Figure 1, it is notable that although synthetic PPAs were only introduced in 2015, they have accounted for roughly the same installed capacity as bank hedges over the past three years.

While we cannot predict which contracted and hedging structures will predominate in the future, there are two significant changes that will affect this choice for wind projects. In the near term, the production tax credit (PTC), the largest incentive for wind projects, is phasing out, with projects that commence construction in 2019 receiving a 60 percent reduction in the PTC and no credit for projects starting afterwards. The phase-out of the PTC will cause a reduction in wind capacity installed, and projects that are installed will likely choose revenue structures with less risk, such as physical PPAs.

In the long term, because they cannot choose when to generate, increasing wind and solar on the grid will progressively reduce electricity prices when the sun shines or the wind blows. Without sufficient energy storage or flexible demand, models indicate that rising levels of wind and solar penetration will lead to lower median electricity prices but higher prices during times of scarce supply. In other words, revenue risk will increase for merchant wind generators, which would favor physical PPAs and less risky hedging designs. Of course, utilities and hedging counterparties would place a greater discount on wind as risks to the value of wind rise. Considering the risks to merchant wind generators provides a clear understanding of the risks to all wind generation, and doing so reveals what will be needed if wind is to continue to grow for many years to come.

*Figure 7 in "Reducing Risk in Merchant Wind and Solar Projects through Financial Hedges."