Workers, advocates, local officials, unions, and businesses in the oil and gas–producing regions of New Mexico spoke with researchers at Resources for the Future about how the federal government can contribute to economic resilience for communities in these regions as the United States—and the world—transitions to a low-carbon economy.

If the federal government wants to achieve national climate goals, the United States must accomplish nothing less than a transformation of its energy sector. Because of the speed and scale at which these changes need to occur, no historical precedent exists to serve as a guide in this energy transition. But in many regions across the United States, federal energy policy already has transformed lives and landscapes and even entrenched myriad new collective identities.

Everyone has a relationship to the fossil fuel sector, but only a fraction—0.5 percent of the US workforce—actually works directly in fossil fuel industries. Though half of a percent may not seem like much, the importance of the US fossil fuel industry for producing regions is outsized, because the business is concentrated around the geographic sites of extraction. This concentration means that many communities are supported almost entirely by a single economic activity, and, when conditions change, securing prosperity can be, as one interviewee stated, a “fight for our lives.”

By Mistake or Design?

In most oil and gas–producing regions, the presence of the fossil fuel industry is explained by the random distribution of the Earth’s resources—economists informally call this random distribution of resources “manna from heaven.” However, the early development of oil and gas in New Mexico had just as much to do with the relationships among private landowners, Native nations, nascent state governments, and federal agencies as with the presence of oil and gas.

The origin of the oil and gas industry in New Mexico, which was an early US territory, is inextricably entwined with US imperialism. The first oil well that was drilled in New Mexico was on sovereign Navajo land and was the explicit project of US Secretary of the Interior, Senator, and convicted felon Albert B. Fall (R-NM), which he initiated under President Warren G. Harding in 1921. (Energy history buffs will recall Fall’s role in the infamous Teapot Dome scandal.)

The Industry Today

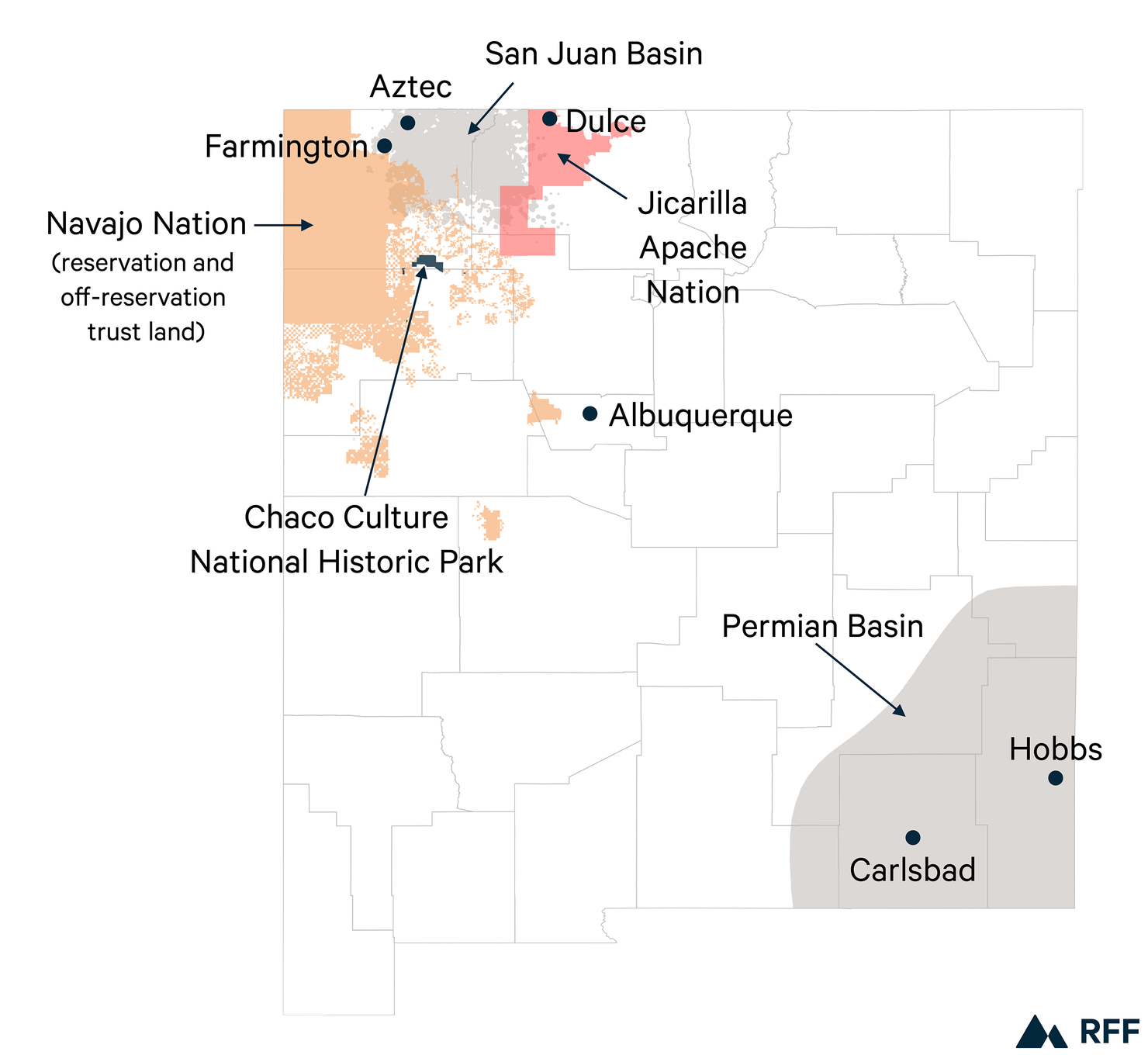

The histories of production in the state vary substantively. In New Mexico, oil and gas extraction takes place primarily in two basins: the San Juan Basin, where the first wells in the state were completed, and the Permian Basin, the oil field that has propelled the return of the United States as the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. Notably, the Permian stretches across New Mexico and Texas, with higher wages and more industry concentrated on the Texas side.

Figure 1. Native Nation Land and Oil and Gas Basins in New Mexico

Data source: Map by the authors. Notes: The cities that are labeled in the figure are the cities that we visited during our research for our recent report.

While the economy-wide process of decarbonization remains in its early stages, our recent work with Resources for the Future (RFF) colleague Brian C. Prest demonstrates that a fiscal fallout for oil and gas communities could unfold in the coming decades, depending on domestic and international climate policies and commodity prices. Given the federal government’s role in ushering in oil and gas production in New Mexico and the need for rapid emissions reductions, policymakers are seeking tools to ensure that these communities are economically resilient in the years and decades ahead.

Fortunately, many solutions for building economic resilience lie in the lived experience of those who are working to improve the quality of life for oil and gas workers and their communities. On a recent trip to New Mexico, we conducted interviews with 47 individuals from 22 diverse organizations to draw out these insights.

In a new report, we share these insights for decisionmakers who seek to understand whether and how new policies can help build economic resilience in oil and gas–producing communities. As with all interpretations of history, our understanding of the situation is imperfect, particularly because we do not live in and cannot speak for these communities. However, we believe that our insights are useful for decisionmakers, and we plan to build on our findings through future research that engages with other oil and gas communities around the United States.

Key Takeaways

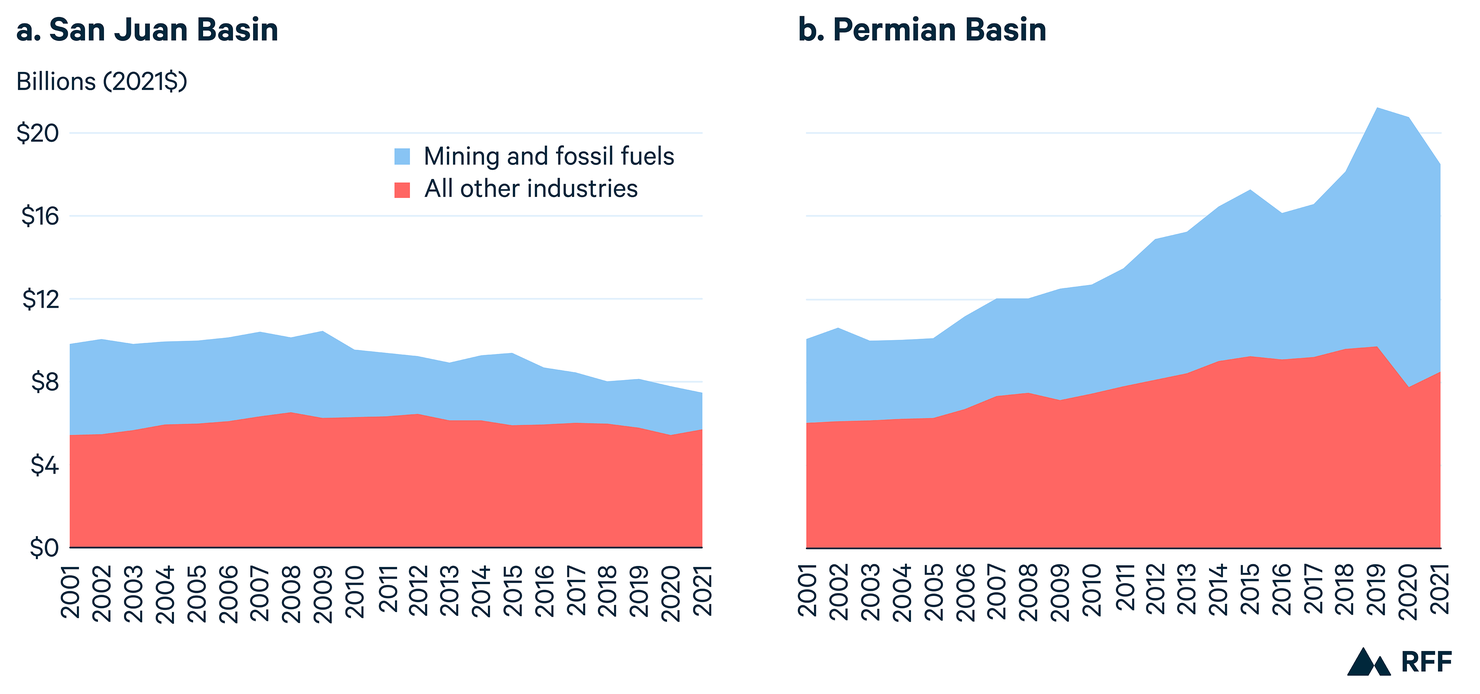

A key takeaway to help frame potential policy interventions is that the San Juan and Permian Basins are at different stages of energy development and likely will need to pursue different strategies for economic resilience. In both basins, local stakeholders were skeptical but willing to work directly with the federal government on economic development. But they also identified barriers, most prominently citing a lack of administrative capacity when seeking access to federal support. Most interviewees said that future federal efforts would succeed only if the strategies include local capacity building or a much less burdensome administrative process for accessing and administering federal funds.

Figure 2. Economic Output from the Fossil Fuel, Mining, and Other Industries in the San Juan and Permian Basins in New Mexico

Data source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis for gross economic output data. Notes: “Economic output” refers to the total value of goods and services produced annually.

Another sentiment that interviewees shared is that solar and wind energy development are unlikely to replace jobs and tax revenue from fossil fuels. Jobs in the fossil fuel sector are understood to be “family supporting”; in other words, these jobs often pay over $100,000 per year, whereas renewable energy development tends to pay less. Although concentrating more of the renewable supply chain (e.g., component manufacturing) in the San Juan and Permian Basins could help mitigate the loss of these jobs and revenue, neither region has attracted such investment in this supply chain to date.

Could other economic sectors grow to sustain these oil and gas communities? Perhaps, but our interviewees diverged on visions for which economic sectors offer the most promise. Some stakeholders strongly supported emerging energy-sector solutions, such as attracting a federal “hydrogen hub,” building new nuclear facilities, or expanding natural gas development, while others strongly opposed such strategies. (Just last week, President Joe Biden announced the locations of seven hydrogen hubs, and New Mexico’s joint proposal with Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming was not among them.)

Finally, regardless of which sectors local stakeholders choose to pursue, investments in physical and social infrastructure, such as broadband internet, transportation, and health care, will be essential building blocks. One common sentiment among interviewees was that the federal government should enable local groups to have more flexibility in using federally owned lands, which are extensive in both basins. For tribal communities, navigating federal bureaucracy can be particularly frustrating: one tribal official stated, “We gave you the land, and we don’t ask for reports!”

Altogether, our research is an attempt to convey the sentiments and priorities drawn from the lived experience of oil and gas community members. For about a century, residents of these basins have borne the environmental and health burdens from the energy extraction that continues to power the US and global economies. As a country, the United States is just beginning to come to terms with this legacy. In the years ahead, much more work will be needed to understand the priorities of community members, identify which policy solutions are best suited for different regions, and develop the mechanisms that can deliver support most effectively.