Decentralized forest management is often considered to be a valuable tool for ecological and socioeconomic advancement within developing nations. However, recent work has shown that its effectiveness is highly dependent on the quality of local governance.

Probably the most important trend in developing countries’ forest policy over the past several decades has been decentralization—the transfer of management authority from the national level to states, villages, and local communities. More than a quarter of all developing countries’ forests are now managed by local communities—well over twice the share for protected areas.

According to advocates, decentralized forest management (DFM) both improves forest health and boosts local livelihoods by empowering actors who have the best understanding of local conditions, extending their planning horizons, and redirecting human and financial capital to the local level. But case studies suggest that, in practice, these benefits can be elusive. DFM initiatives sometime fail to spur meaningful shifts in power, and even when they do, can lead to recentralization. Given this mixed track record, careful empirical study is needed to understand whether, under what conditions, and how DFM has ecological and socioeconomic benefits.

Evidence on DFM has been accumulating steadily since the 1980s, when the topic first gained currency in policy circles. However, most of this evidence comes from qualitative case studies, which, although they’re invaluable, have limitations. Relatively few studies use experimental and quasi-experimental methods that aim to draw causal inferences by controlling for confounding factors.

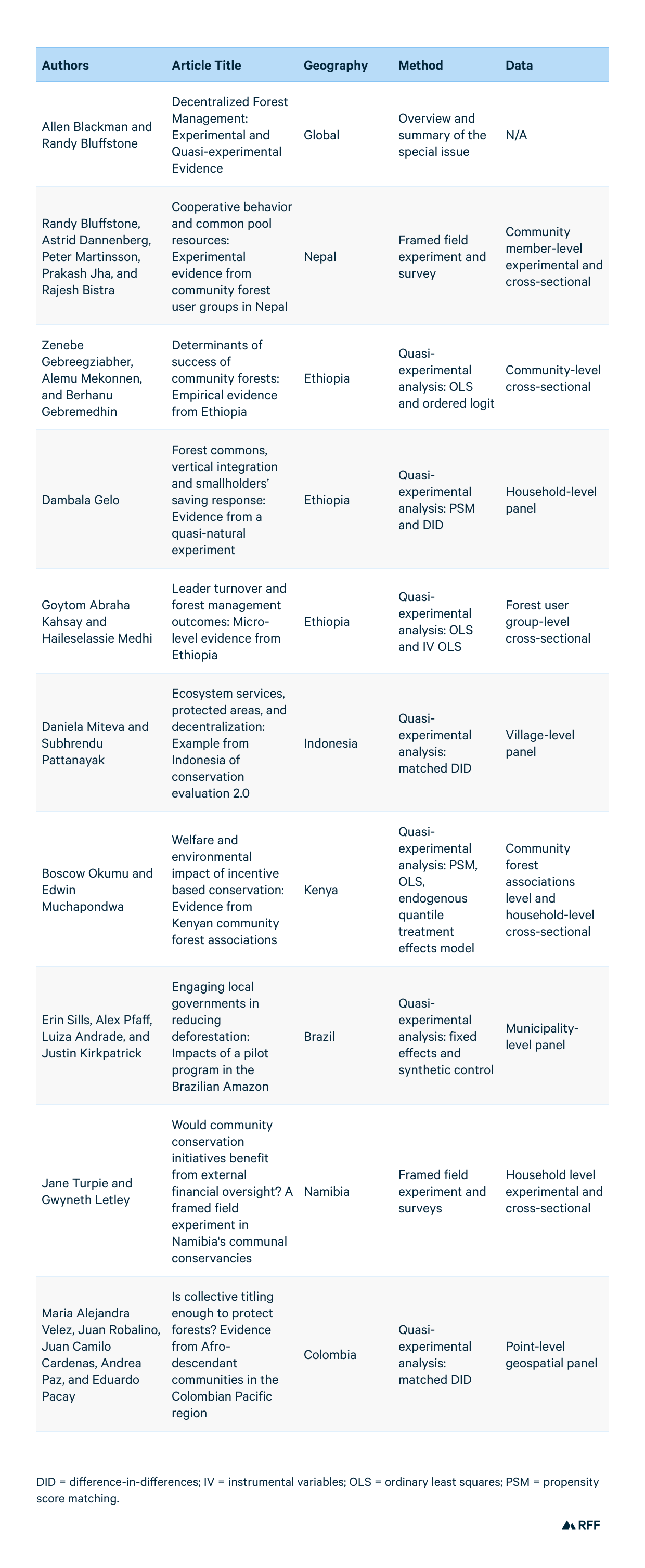

To help fill this gap, the Environment for Development Initiative, of which RFF is member, organized a special issue of the journal World Development titled “Decentralized Forest Management: Experimental and Quasi-experimental Evidence.” It features nine rigorous empirical studies of DFM interventions, policies, and governance structures in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, along with an overview by the special issue editors (Table 1). All nine studies feature Environment for Development researchers.

Table 1. Summary of Articles in the Special Issue of the Journal “World Development”

Taken as a whole, the studies offer two broad policy lessons. First, as advocates claim, DFM interventions can improve ecological and socioeconomic outcomes. For example, one study shows that providing land titles to Afro-descendant communities has reduced deforestation by an average of 30 percent in Colombia, although the magnitude of this effect varies substantially across subregions. However, such improvements are by no means guaranteed; some interventions clearly do not have the desired effects. For example, another study—which analyzes the effect of district splits, elections, and mayoral turnover on deforestation, fires, and forest fragmentation in villages in and near protected areas in Indonesia—indicates that district splitting and mayoral turnover can weaken enforcement inside protected areas with regard to deforestation and forest fragmentation.

The second broad lesson of the special issue is that, perhaps not surprisingly, the success of efforts to transfer authority to the local level depends critically on conditions at the local level—most notably, governance capacity. We can draw an example from a study that assesses the effects of leader turnover in community forest user groups in the Ethiopian state of Oromia, which shows that forest user groups with more responsive leadership have higher incomes, less income inequality, and healthier forests.

These two broad policy lessons jibe with evidence from qualitative case studies. The nine articles compiled for the recently published special issue provide rigorous evidence that the advertised benefits of DFM can be realized; pinpoint the local conditions that facilitate that result; and shed light on interventions, specific research questions, and geographies that are new to the literature.

This article has been reprinted with some changes and with permission from the Environment for Development website.