Memorial Day weekend is upon us and like many Americans, we’re looking forward to the unofficial launch of the summer holiday season. Our plans might include a visit to a national or state park—nearby Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, for example, or Assateague Island National Seashore in Maryland, or closer to home, Great Falls Park.

We’re not alone. Signs point to Americans having a growing interest in the outdoors. As we’ve discussed in podcasts and blog posts, the popularity of national parks is on the rise, with park campgrounds filled to the brim in the peak summer seasons. We also wrote about the growing outdoor recreation economy movement, including the recent establishment of outdoor recreation offices in several states to promote tourism and economic development around outdoor recreation and public lands.

Do your plans for the long weekend include visiting America’s public lands? Your answer may depend on which racial or ethnic groups you belong to.

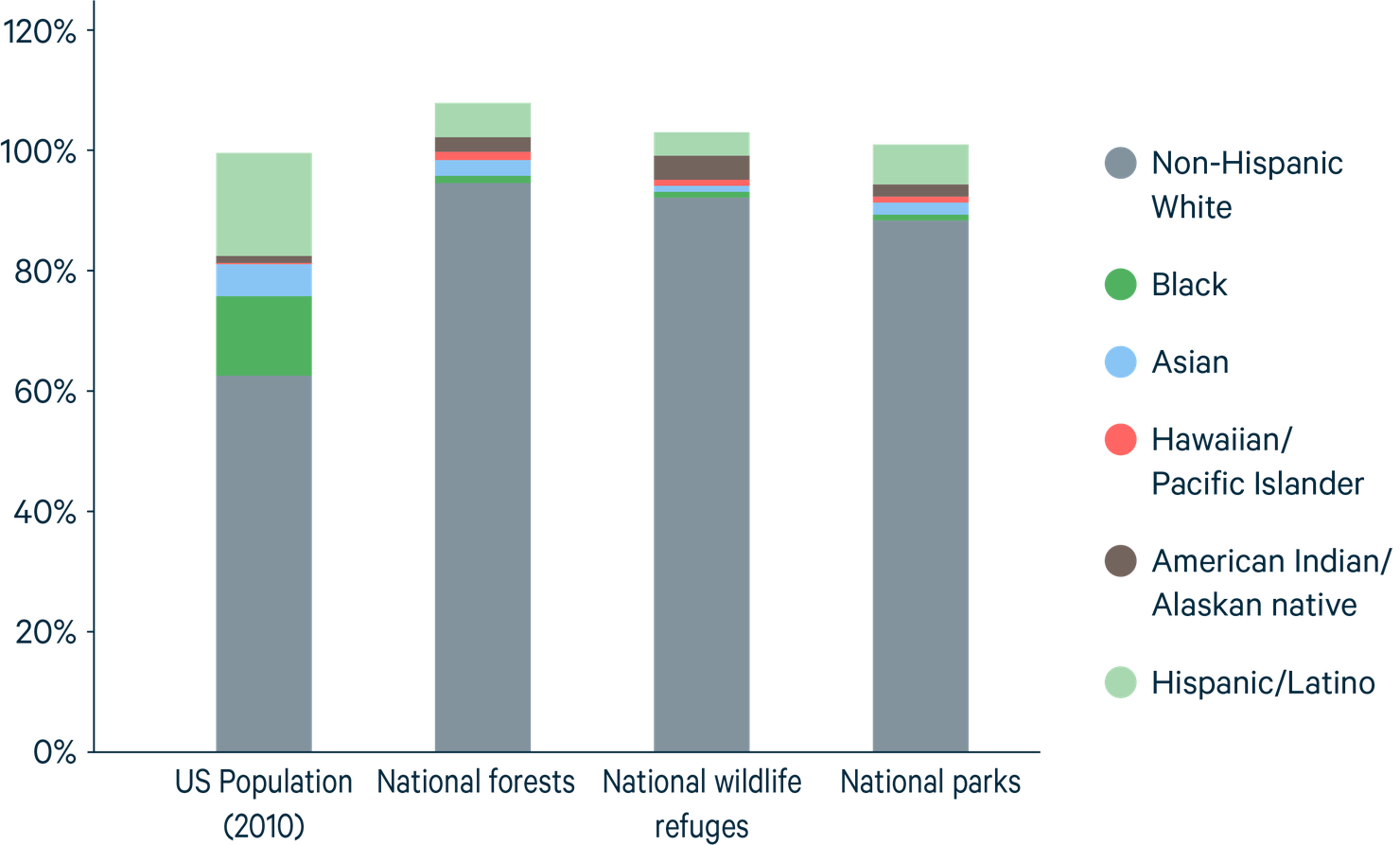

Data from the US Forest Service, National Park Service, and Fish and Wildlife Service suggest deep inequality in the ethnic/racial mix of visitors to our public lands. While the most recent US census shows that non-Hispanic whites make up approximately 63 percent of the US population, they comprise between 88 and 95 percent of all visitors to public lands (Figure 1). African Americans comprise only 1 to 1.2 percent of all visitors and Hispanic/Latinos between 3.8 and 6.7 percent; both groups are underrepresented as visitors to public lands relative to their presence in the population at large.

Figure 1. Visitors to Public Lands and US Population by Ethnic/Racial Group

Note: The national forest and national wildlife refuge surveys allowed respondents to select more than one ethnic/racial identity, thus the totals are greater than 100 percent.

Interestingly, this disparity across racial and ethnic groups is not reflected in an annual national survey by the outdoor recreation industry. The survey, which covers a wide variety of outdoor activities, including mountain biking, fishing, camping, and much more, finds that overall participation rates for Hispanics, whites, and Asian Americans are around the same at 50 percent, all higher than the participation rate for blacks at 34 percent. But it also finds that Hispanics and blacks who do recreate spend more time doing so: 87 and 86 outings per year, on average, respectively, compared to 76 for whites and 74 for Asians.

Why, then, do we see differences across racial and ethnic groups for public land visitation? If African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos are spending time outdoors, as the survey suggests, why not in national parks, national forests, and national wildlife refuges?

Barriers to Participation in Outdoor Recreation

Researchers and outdoor advocates have pointed to several potential barriers to minority enjoyment of public lands.

- Affordability and Access. Visiting remote national parks such as Glacier or Yellowstone can be expensive and time-consuming, presenting significant obstacles to lower-income Americans, especially hourly workers with limited vacation time. Even closer-to-home sites such as state parks often have entrance fees, and some outdoor recreation activities—including camping—require expensive equipment.

- Early Childhood Experiences. Some experts writing on this topic have highlighted that early childhood experiences of engaging with the natural world can shape a person’s views of self-confidence and enjoyment of nature well into adulthood. One of the organizations working to change this pattern, City Kids Wilderness Project, has been serving youth in the District of Columbia since 1996. They bring DC students to Jackson, Wyoming, for an intensive program of experiential learning through outdoor recreation. Check out this recent video about their work.

- Cultural Factors. David Scott and KangJae Jerry Lee wrote in the George Wright Forum in 2018 that cultural factors provide people with a “template” about the kinds of outdoor recreation—and leisure more generally—they feel they need to conform to. Thus, cultural factors can facilitate participation in outdoor activities by some groups but inhibit it for others. Ambreen Tariq, an Indian-American Muslim woman, describes her experiences being the only woman of color in many outdoor recreation settings in an article for the REI Co-op Journal. For her, enjoying the outdoors includes overcoming feelings of not fitting in. She started the Instagram account @BrownPeopleCamping to promote diversity in the outdoors and help people like herself find a community. For a poignant but comical take on what it’s like to be “the only one” read, J. Drew Lanham’s “9 Rules for the Black Birdwatcher”.

- Discrimination and White Racial Frames. Prior to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, African Americans were banned from, or segregated at, public recreation sites, including national and state parks. This legacy lives on, and many minorities report feeling excluded at parks where interpretive exhibits and historical information often feature only white Americans. The problem is exacerbated by a lack of diversity among park rangers and other employees: 83 percent of National Park Service employees are white; 62 percent are male. The outdoor recreation industry is no better. Marinel de Jesus comments on the white- and male-dominated nature of the industry and how far it has to go to diversify both its customer base and workforce.

- Historical Trauma and Concerns of Physical Safety. In a 2018 study, survey participants were asked to describe why African Americans might be fearful of visiting forests. According to the paper, 66 percent of participants did discuss thoughts and experiences which suggest that the historical trauma of slavery and lynchings in Jim Crow era is associated with the environment for many African Americans. In this paper, 19 year old Pharaoh explains: “. . . So, nature is not something for Black people, um they killed us a lot in nature. They would do a lot of wild things, like plantations . . . . Yeah they would hang us in trees, so maybe that’s why black people don’t go to the forest, don’t want to see a tree.” This can also be seen in the popular Billie Holiday song “Strange Fruit” where she poignantly sings “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

All of the above suggests a very real concern exists in communities of people of color regarding not having significant community support or not feeling safe in our public lands.

The Path Forward

Things are slowly starting to change, however. Women and people of color are leading the way by working to improve the way that outdoor recreation is represented in the public sphere and creating spaces where people of color feel encouraged to take part in the great outdoors. Rue Mapp, Founder and CEO of Outdoor Afro, explains in this video how her organization ties outdoor recreation activities to black history to help African Americans re-establish relationships with America’s public lands. In addition to Outdoor Afro, other active groups include Latino Outdoors, The Black Outdoors, Pride Outside, and Diversify Outdoors. People who are looking to get outside but do not want to be “the only one” of their particular community might find a home in one of these organizations.

In our view, two policy moves would also help. The first is increased funding for state and local parks. The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), which has been the primary source of federal funding for parks and conservation since 1965, includes a stateside program that provides grants for state and local park projects. The LWCF was recently reauthorized as part of the John Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, but as we’ve shown in previous posts, the stateside LWCF program has dwindled over the years. In 2016, $110 million was distributed to the states through the LWCF, and although this was more than double the spending in the prior ten years, it was only 20 percent of the average spending (in inflation-adjusted dollars) in the first 15 years of the program. Providing more public lands closer to where people live will improve access to outdoor recreation for people with more limited financial resources and could go a long way to promoting diversity in parks and public lands.

Our second recommendation is directed at the new state outdoor recreation offices. As these offices promote economic development around public lands and outdoor recreation—which is an emphasis in all of these new offices—they should make diversity a focus. Utah, for example, provides grants for development of outdoor amenities in rural communities with revenues from a hotel tax. The state could target these funds to more diverse communities, including Native American tribal communities. New Mexico, one of the newest states to establish an outdoor recreation office, could be leading the way. The state has established an “Outdoor Equity Grant Program,” which partners with private businesses to provide grants to offset some of the costs of outdoor recreation for low-income youth, including equipment costs, entrance fees, and travel costs. Following up on the effectiveness of this new first-of-its-kind state initiative will be important and provide lessons for other states.

These policy moves are not enough, however, and it is critically important not to rush into a new diversity initiative or costly new programs without first understanding the landscape, having many conversations with people in diverse communities, and developing policies and programs in tandem with the communities you intend to serve. Not doing this engagement can create a great backlash. Diversity initiatives, and other such measures are important first steps towards having more inclusive national parklands but further study must be done into the root causes for this situation in order to develop better informed policies at the national level.

Lastly, whether you are preparing for this weekend by packing up for a family road trip to visit one of America’s parklands or national monuments, spending time outdoors enjoying family barbeques, playing sports, or listening to your favorite songs while sipping sweet tea on your front porch, let us remember: “This land was made for you and me.”

This land is your land, this land is my land

From the California to the New York island

From the Redwood Forest, to the Gulf stream waters

This land was made for you and me

As I went walking that ribbon of highway

I saw above me that endless skyway

And saw below me that golden valley

This land was made for you and me.

—Woody Guthrie, 1940