The climate crisis requires a transformation of our transportation system—one that will likely involve vehicle electrification, public transit, denser land use, and reduced personal vehicle travel. The Transportation Climate Initiative (TCI)—a coalition of 12 states and the District of Columbia—proposes to work toward this goal with a cap on transportation emissions, investment of cap revenues in clean transportation options, and coordinated regulations. While climate change is the chief motivation for this initiative, TCI leadership recognizes that, to achieve the broad support necessary for implementation, it must also address more immediate transportation concerns such as local air quality, transportation access, and affordability.

A new report we’ve coauthored with Resources for the Future Senior Fellow Karen Palmer explores the trade-offs and opportunities involved in meeting these multiple transportation goals. This report is the third in a series of studies that also examine the electricity sector impacts of decarbonizing transportation and program design options for managing carbon revenue uncertainty. In our new report, we examine the outcomes of transportation policies—including a carbon price and revenue investment options—across various metrics relevant to the multiple goals of transportation policy. We do so using a model which takes as its animating concept that every policy will have environmental, health, and economic impacts and that each of those impacts will be distributed differently across the population.

The project has led us to the following five key insights:

Some policies, such as electrification of light duty vehicles, are better at reducing CO₂ while others, such as electrification of heavy-duty vehicles, are better at reducing criteria pollution. Policymakers balancing the two goals may want to prioritize policies that reduce criteria pollution in locations that are disproportionately burdened by pollution. Policies such as electrification of school buses and public buses, or heavy trucks in densely populated areas, might help achieve this balance between air-pollution benefits and CO₂ reductions.

Transit users and people living near transit benefit financially from a different portfolio of policies than vehicle users. Figure 1 illustrates this result in a region that’s comparable to the northeastern United States, with a carbon price sufficient to raise $1 billion each year and policies that invest $1 billion in various ways. Employing both transit- and vehicle-friendly policies would yield benefits across a wider swath of households. Adding public transit in areas that have not previously had any transit options, or making electric vehicles available to those who might not otherwise be able to afford a new car, would expand the reach of both types of policies.

Figure 1. Distribution of Financial Effects across Households with Different Types of Transportation Usage (Northeast Census Region, 2022)

A trade-off exists between policies that have immediate effects and others that have smaller effects in the near term but potentially larger effects in the long term. Policies with immediate effects include options such as transit subsidies. Policies with longer-term effects that cumulate over time include those that facilitate land use change and those that encourage capital stock turnover.

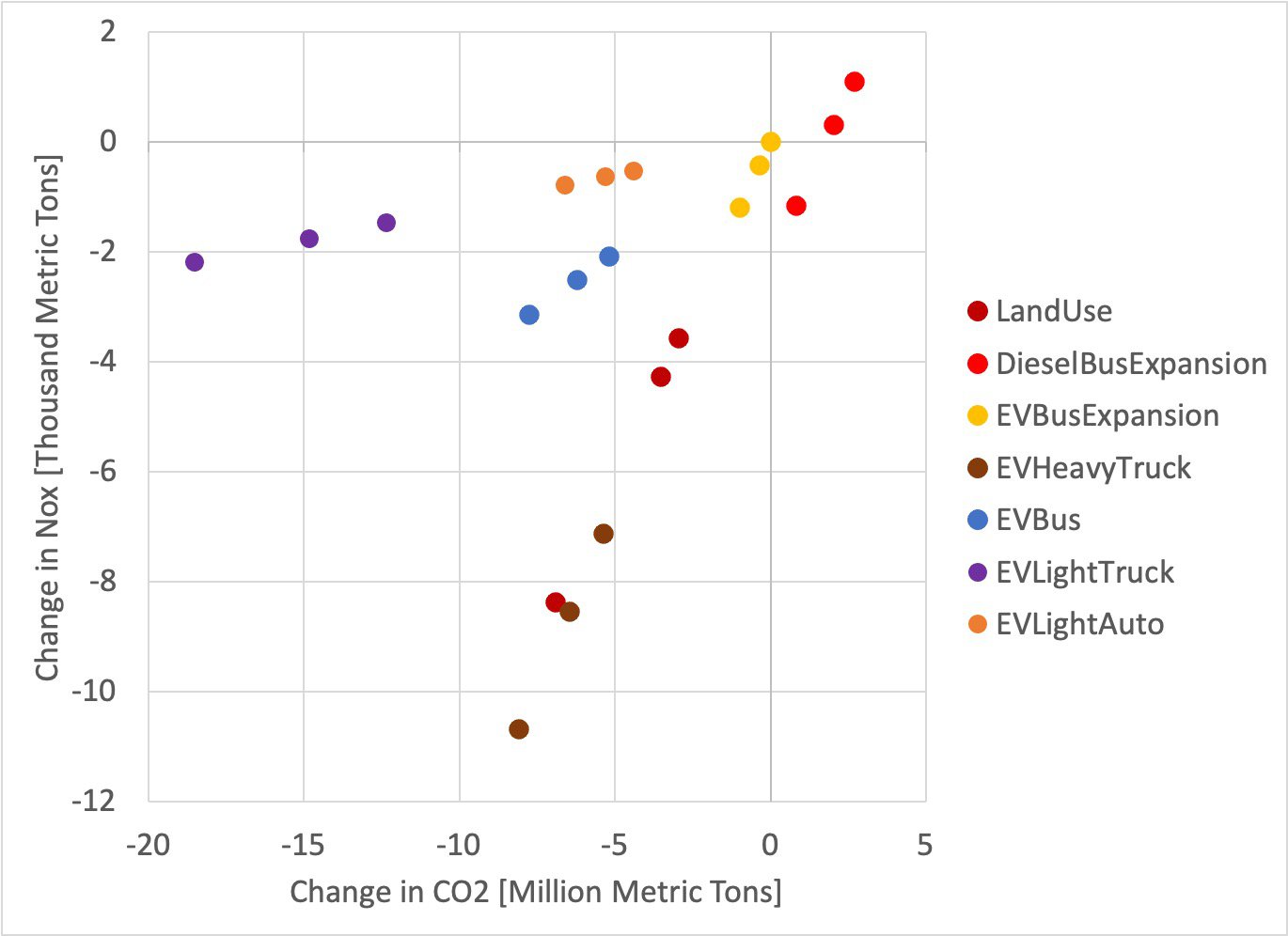

All policy outcomes are uncertain, but their uncertainties derive from different issues and leave broad patterns of reductions in carbon and criteria pollution unchanged. Land use change policies have some of the greatest reduction potential, with uncertainty deriving from the many intermediate steps between a zoning change and households moving to denser locations. Vehicle turnover policies also have strong reduction potential, with uncertainty deriving from future vehicle prices (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Uncertainty in CO₂ and NOₓ Outcomes (2032)

Many transportation policies yield outcomes that are highly granular or difficult to quantify. For example, public transit expansion policies implemented in different locations will have different levels of effectiveness and will benefit different households. Such policies also affect household access to essential services and may change housing costs. Community engagement, which is critical to achieving political support for efforts such as TCI, will allow these effects to be considered.

Taken together, this research does not offer a single policy as the best way to decarbonize the transportation sector while meeting other transportation goals. Rather, we illuminate trade-offs among transportation policies as TCI states consider investments of carbon revenue. As jurisdictions look to clean up the transportation sector, a portfolio of policies—along with the intentional engagement of community partners—may best allow them to balance air pollution reduction and carbon reduction, the transportation needs of transit users and vehicle users, near-term and long-term benefits, and certain versus uncertain outcomes.