Within the next few months, it is expected that the Trump administration will introduce the final rule in its rollback of passenger vehicle fuel economy and greenhouse gas standards. When the original rule was announced in the summer of 2018, the agencies in charge had published a preliminary regulatory impact analysis (PRIA) of the administration’s plan to ease the proposed standards for model years 2021-2025. This PRIA included a detailed calculation of costs and benefits and found that freezing the standards at 2020 levels would lead to net benefits. Unfortunately, the cost-benefit analysis was riddled with significant modeling flaws, as detailed in a co-authored paper that we published in Science last year.

As we discussed in that paper, the agencies could address these flaws by incorporating an integrated economic model of consumer and producer choice into their cost-benefit analysis. In a prior RFF blog post, we suggested that the agencies could also account for credit trading when computing the costs and benefits of the standards. Since 2012, the standards have essentially set up a cap-and-trade system for emissions where manufacturers can comply either by raising fuel economy and lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or by buying fuel economy and greenhouse gas credits from overly compliant manufacturers.

The PRIA includes a model of manufacturer compliance behavior that omits the credit trading option altogether. Theoretically, this artificially inflates both the costs of the standards and the potential savings of rolling back the standards. Credit trading lowers compliance costs by equating marginal costs of increasing fuel economy across manufacturers. Previous economic research has shown that marginal costs across manufacturers are quite heterogeneous, suggesting that the compliance cost savings from credit trading could be substantial. Prior literature using simulation-based methods estimates cost savings from credit trading to be between 15-20 percent. Incorporating credit trading into a cost-benefit analysis could dramatically shift results then, perhaps even making a rollback of standards costly on the net rather than beneficial.

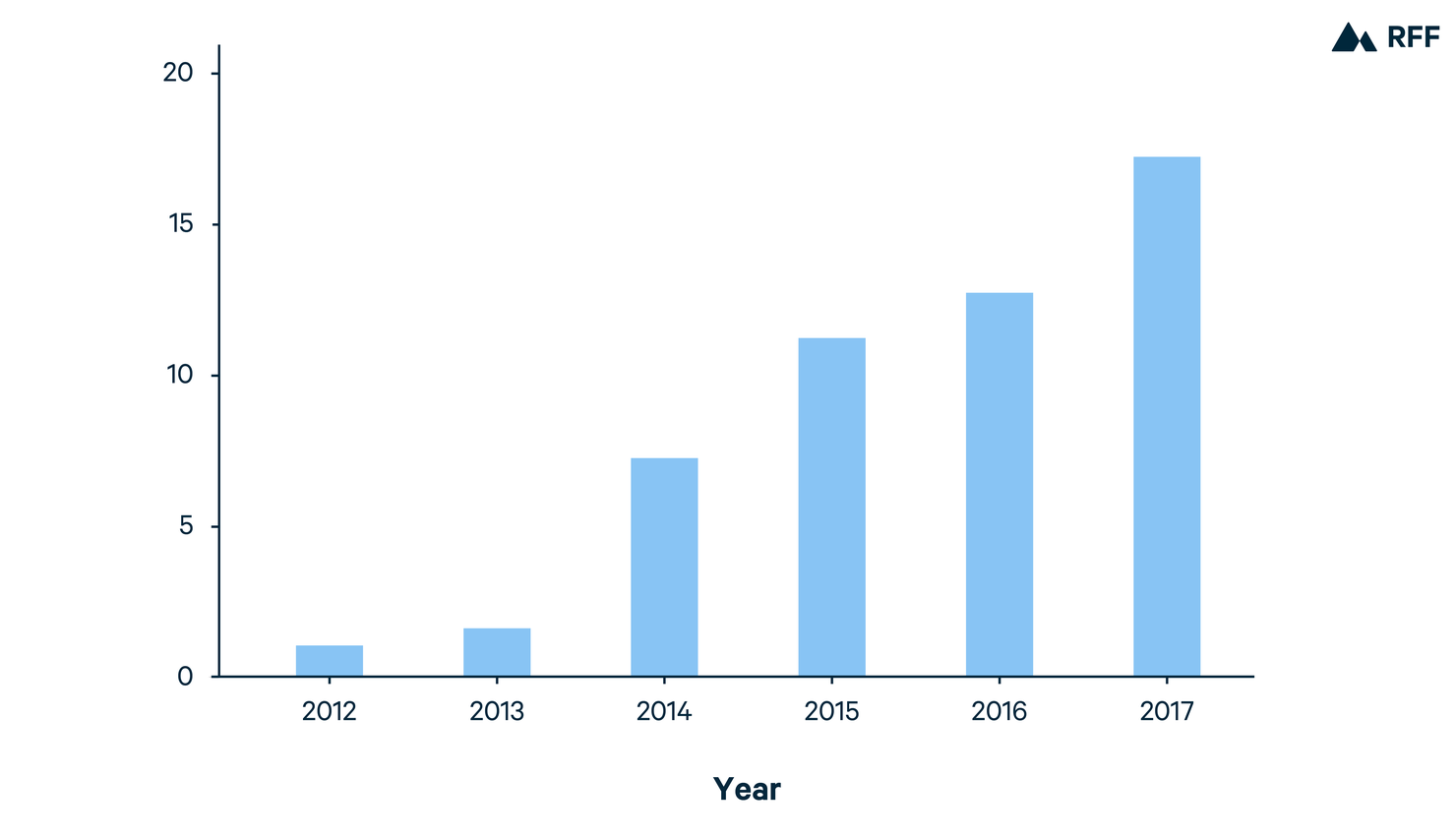

In our prior blog post, we showed that credit trading became increasingly relevant through model year 2016, with credit sales increasing each year. Now, based on new data from 2017, we know that credit trading is becoming an even larger source of manufacturer compliance.

Figure 1. Annual EPA GHG Credit Sales (Million Mg)

In Figure 1, we plot the reported quantity of EPA GHG credits traded in each compliance year during the first six years of the credit trading program. The data show a strong upward trend in the number of credit sales.

Credit trades among individual manufacturers for the 2017 compliance year are reported in Table 1. These trades show how the credit-trading program allows for flexibility in the types of vehicles manufacturers produce and sell. As in past years, Tesla and Honda continue to sell large numbers of credits to Fiat Chrysler Automotive (FCA). Tesla, with its fully electric fleet, and Honda, which produces vehicles with emissions well below requirements, are able to sell their excess credits to Fiat Chrysler, which primarily makes heavy vehicles like trucks.

Table 1. EPA GHG Credit Trades for Compliance Year 2017

|

Credit Vintage |

Buyer |

Seller |

Credit Sales (Mg) |

|

Expires 2021 |

FCA |

Tesla |

2,500,000 |

|

Expires 2021 |

FCA |

Honda |

5,900,000 |

|

Expires 2021 |

Jaguar Land Rover |

Toyota |

1,400,000 |

|

Expires 2021 |

Volkswagen |

Toyota |

3,000,000 |

|

Expires 2022 |

BMW |

Honda |

2,000,000 |

|

Expires 2022 |

FCA |

Tesla |

2,400,000 |

Sources: Author calculations based on the Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards for Light-Duty Vehicles:

Manufacturers Performance Reports EPA 2018, 2019. We base credit trading partners on prior year trading activity.

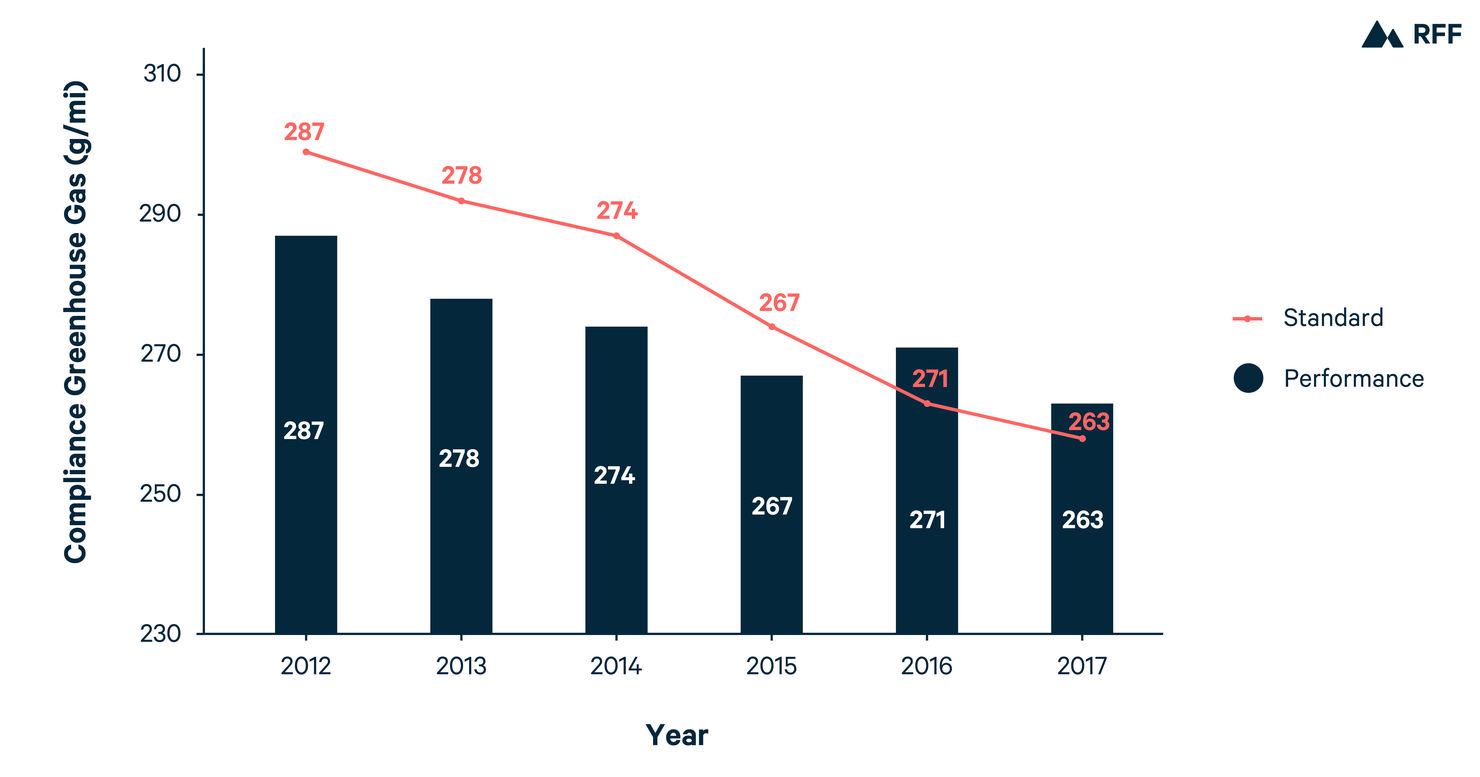

Although there are large credit balances held by the industry as a whole, the credit market is expected to tighten as the stricter requirements kick in. Similar to 2016, we find that in 2017 most manufacturers ate into their credit balances rather than replenish them with new credits (Tesla and Honda were exceptions). For the industry as a whole, credit balances are declining after reaching a peak in 2015. Figure 2 displays this history.

Figure 2A. Annual Compliance and Credit Balances for GHG Standard

Figure 2B. Annual Compliance and Credit Balances for GHG Standard

As the credit market tightens, we would expect both more trades and higher prices. Incorporating this credit market and its role in manufacturer compliance is essential for modeling costs and benefits of the regulations, and the current PRIA misses that context.