The coronavirus has temporarily reduced global emissions—but the pandemic could ultimately prove detrimental to the world's climate change trajectory.

That’s because, as much of the world struggles to contain COVID-19 and minimize the toll of the simultaneous economic recession, the UK government was forced to delay pivotal climate talks until next year. COP26 was supposed to be the setting where nations would announce more ambitious emissions reduction goals to align with the objectives laid out in the Paris Agreement. But now, especially with key questions from last year still unresolved, the future of the conference—and of global climate change policy—is uncertain.

The conference’s delay, while a complication brought on by an unexpected pandemic, could also be exposing structural issues with how the world has approached climate policy. The Paris Agreement benefits from near-universal participation (notably excluding the United States) but, absent a strong enforcement mechanism, has relied on voluntary cooperation. And at a time of deep economic crisis, some nations have little ability or incentive to significantly reduce emissions. Would an alternative arrangement be preferable?

Two new papers, both coauthored by RFF University Fellow Simon A. Levin and both published in Nature Scientific Reports, use game theory to assess hypothetical arrangements for international agreements and offer lessons for climate change negotiators. While the delay of COP26 could impede the world’s efforts to address climate change, Levin and his coauthors’ findings suggest that hope still exists for "polycentric" arrangements like the Paris Agreement—or future environmental agreements that shape the incentives for countries to reduce emissions in innovative ways.

The first paper (Vasconcelos et al), published June 8, illuminates an underappreciated benefit of the Paris Agreement: its decentralized structure, which allows for “overlapping coalitions” of nations along with “cities, regions, businesses, and other non-state actors.” This “polycentricity” could prompt benefits that are comparable to—or even better than—a more traditional coalition.

Levin and coauthors construct a series of games that multiple actors play according to either full or incomplete knowledge of the outcomes of their options. The uninformed players base their decisions entirely on the outcomes of the different behaviors they can observe, attempting to maximize personal gains under a range of coalition structures by evaluating the payoff that results from those observed behaviors. Ultimately, the researchers find that creating “multiple overlapping coalitions … enables ‘uninformed’ players to recognize marginal gains of cooperation,” which leads them to act functionally similar to “informed” players.

These findings suggest that when a coalition with universal engagement and uniform rules is politically impossible, multiple layers of overlapping coalitions could be a productive alternative. Plus, the researchers posit that such arrangements “may also allow evolution toward a more cooperative, stable, and inclusive singular regime.” So even if the Paris Agreement differs from a “comprehensive regime” structure, it still is helping shape incentives for countries, cities, and companies to reduce emissions.

That doesn’t necessarily mean a decentralized agreement driven by voluntary contributions is the ideal vehicle for climate policy—especially considering that nations might not have clear incentives to reduce emissions. Levin’s second recent Nature Scientific Reports article (Molina et al), published June 19, wonders how best to encourage self-interested countries to act for the world’s collective benefit, without a central authority enforcing rules and punishing nations that deviate from their promises. The researchers clarify the potential value of “matching-commitment agreements,” whereby a country commits to additional emissions reductions—but only if another country reduces their emissions, as well.

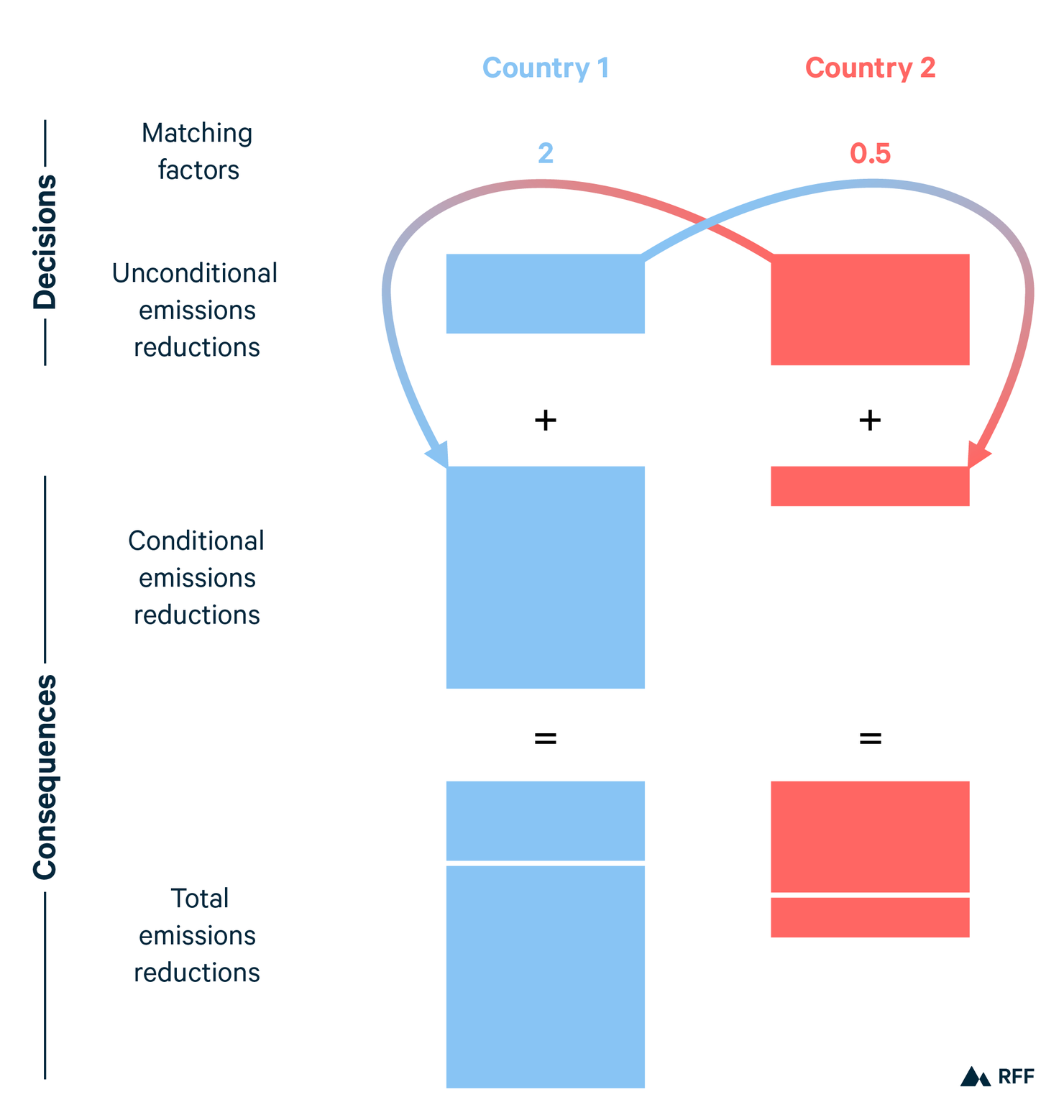

The authors analyze two games, one in which two hypothetical countries make decisions around emissions without any agreement in place, and one in which each country is prompted to independently choose both unconditional emissions reductions and emissions reductions that are dependent on the other country’s plans. As Figure 1 makes clear, a country might reduce its own emissions only slightly at the outset, but commit to further reducing its emissions by double the rate of emissions reductions planned by another country.

Figure 1

This “matching climate game” helps countries to declare ambitious climate goals, despite a reluctance to reduce emissions too much relative to another country; subverts the need for a higher authority to prescribe emissions reductions; and helps countries reduce emissions more than they would have otherwise. In other words, a country skeptical of a rival nation's environmental goals would be loath to announce truly far-reaching commitments under typical arrangements—but would be more comfortable lowering emissions substantially, if that rival nation committed to similar reductions itself. Levin and his coauthors caution that their game shows the interplay between only two nations—whereas some sort of global system of matching-commitment agreements would be infinitely more complex—but posit that such arrangements are still viable.

The state of international climate policy can seem dire—with a pandemic, a recession, and a long-delayed conference all impacting the emissions reductions that countries are willing to promise. Levin and his coauthors write that, based on current emissions reduction pledges, the Paris Agreement “will likely fall short of its goal.” But their conclusion is no guarantee that future arrangements—especially those that incorporate matching-commitment agreements or that build off the polycentric structure of the Paris Agreement—will be fated to fail.