On February 20, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved several market rules for the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO), the organization that manages New York State’s electric power grid. Overall, these orders may make it more difficult for renewable energy resources, energy storage, and demand response resources to participate in the capacity market that serves New York City and many surrounding areas (excluding Long Island). Some critics have compared the orders to FERC’s recent minimum offer price rule (MOPR) in PJM’s capacity market, arguing that the new rules could potentially have similar consequences for investment in clean energy resources and the cost of achieving clean energy goals. However, compared to PJM’s MOPR, the impacts of the NYISO’s buyer-side mitigation rules are likely far less consequential—as long as they remain restricted to these regions and do not set a precedent for capacity market rules in the rest of the state.

Background on Buyer-Side Mitigation

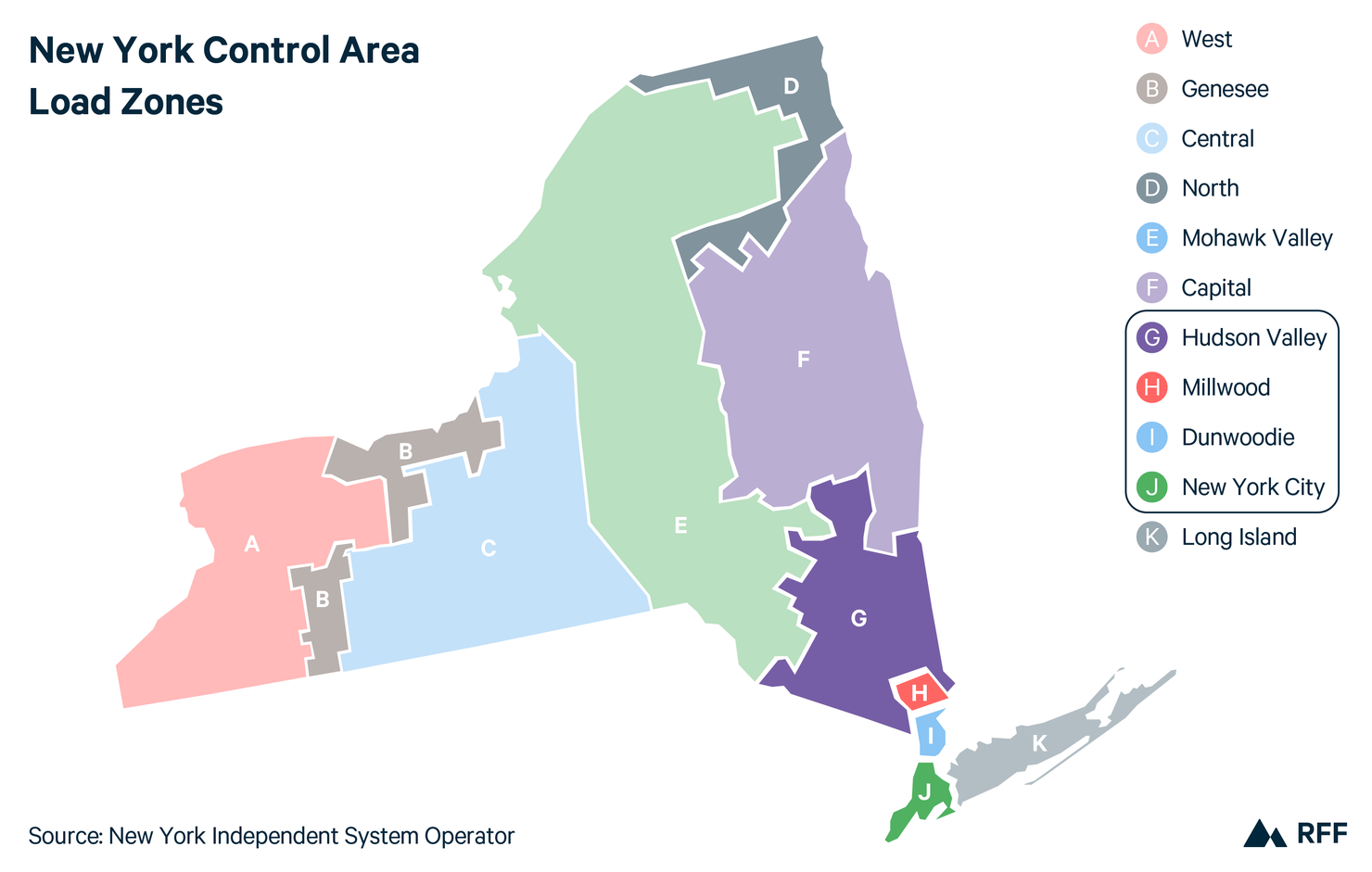

The NYISO’s existing buyer-side mitigation (BSM) rules require that all new resources in “mitigated capacity zones,” which includes New York City and Load Zones G–J (Figure 1), be subject to a price floor when bidding into the capacity market; the price floor is equal to 75 percent of the unit’s net cost of new entry (net CONE). These rules were originally intended to mitigate the impacts of market power exerted by buyers in the capacity market, who also supply capacity and therefore have an incentive to suppress market prices. However, the rules have since been expanded to apply to all new entrants in these areas, which essentially assumes that all new units have price-suppressing capability unless proven otherwise by the economic tests outlined below.

Figure 1. Independent System Operator Zones for the Electrical Power System in New York State

Units are exempt from BSM price floors if they can pass either of the following economic tests:

Part A: The forecast of capacity prices in the first year of the entrant’s operation is higher than the default price floor (equal to 75 percent of mitigation net CONE).

Part B: The forecast of capacity prices in the first three years of the entrant’s operation is higher than the unit-specific net CONE for that unit. Revenues received from renewable energy credits are netted out of net CONE.

Given the wide applicability of the rules, the New York Public Service Commission, New York Power Authority, and New York State Energy Research and Development Authority filed a complaint with FERC in 2015 regarding the NYISO’s BSM rules. The complaint claimed that the existing rules were unjust and unreasonable because they resulted in over-mitigation for buyer-side market power by applying the minimum bid requirement to all new entrants, regardless of whether they were willing or able to exert market power. To correct for over-mitigation, the complaint requested that the NYISO include exemptions for renewables, nuclear resources, demand response resources, and self-supply resources. In response, FERC’s 2015 order sided in part with the complainants and ordered the NYISO to establish exemptions for certain renewables and self-supply resources. The NYISO submitted a compliance filing to FERC in April 2016 that established an exemption for renewables capped at 1,000 megawatts (MW) of installed capacity.

What do the new FERC orders do?

FERC's most recent orders address the NYISO’s compliance filing and respond to other complaints and requests for rehearing regarding the BSM rules and some proposed exemptions. In summary, the orders reject requests that energy storage be exempt from the BSM price floors, partially reverse a previous FERC decision to exempt demand response resources (the new rules will only exempt retail-level demand response programs), and require that the NYISO revisit its calculation of the 1,000 MW cap on total capacity eligible for the renewable energy exemption. FERC directed the NYISO to revise the renewable exemption cap to be tailored to the mitigated capacity zones rather than the entire NYISO, and to be based on unforced capacity rather than installed capacity. Presumably, this direction from FERC will result in a smaller cap for the number of renewables that would be exempt from BSM, meaning that more projects will likely be subject to the BSM price floors.

FERC’s decisions do not necessarily create new obstacles for these technologies, but they do fail to mitigate existing obstacles—some of which would have been addressed by older FERC orders that have now been reversed. For example, in response to a complaint, FERC previously ordered the NYISO to submit a compliance filing that exempted all demand response resources (called “Special Case Resources”) from the BSM rules, but the newest order partially granted a rehearing request for this decision and rejected the NYISO’s compliance filing. Instead, the new FERC order argues that wholesale demand response resources should, in fact, be subject to BSM price floors (except for retail-level demand response). FERC’s justification is that these resources can suppress market prices because they receive state subsidies.

FERC’s orders reaffirm the NYISO’s decision to over-mitigate entry of new resources into the mitigated zone capacity market. While the BSM rules do not directly target resources that receive state subsidies the way that PJM’s MOPR does, the rules do target these resources indirectly. The reason for this is twofold.

First, the way the exemptions are calculated (Parts A and B, detailed above) allows resources with a low net CONE to enter the market without a price floor if the net CONE is lower than the expected capacity market revenues. Net CONE refers to the net cost of new entry and is the revenue a unit needs to make in the capacity market during its first year in operation, accounting for expected revenues from the energy and ancillary services markets, to cover its costs. Resources such as renewables tend to have a higher net CONE relative to others, such as natural gas plants, because the upfront costs of renewables are higher. Second, due in part to New York State’s policy priorities, new resources tend to be renewables, which means that the rules target new, cleaner resources over existing, dirtier resources.

Expected Impacts

The decision to potentially reduce the renewables exemption cap could hinder the ability of renewables to compete in the capacity market in these areas. However, the impacts of this (potentially) stricter cap are likely inconsequential in the near-term, given that only about 1 percent of the existing 7,252 MW of total installed capacity of renewables (including hydro) and less than 1 percent of planned renewable capacity (expected to come online by 2022) in New York State are located in the counties impacted by these rules, according to the US Energy Information Administration’s Preliminary Monthly Electric Generator Inventory from December 2019. The number of renewable projects in these areas could increase in the future, given New York State’s ambitious clean energy goals, but it is more likely that these projects will continue to be pursued upstate, where areas are less densely populated and more land is available for development. Notably, however, New York lacks sufficient transmission infrastructure to move the power produced by upstate renewables to serve downstate load and faces resistance to adding new transmission lines. Unless these transmission constraints are resolved, siting new clean resources in the mitigated capacity zone could become essential for meeting New York’s clean energy goals.

Energy storage could face more significant consequences as a result of these orders. Nearly 320 MW of energy storage, which represents 95 percent of the state’s planned storage capacity, is expected to come online in the mitigated capacity zone within the next two years. FERC’s orders could make it much more difficult for these resources to clear in the capacity market, and thus severely hamper the state’s ability to reach its goal of 3,000 MW of energy storage by 2030.

Also, while these orders may not have a significant impact in the near-term for renewables, they still could set a precedent that eventually brings about buyer-side mitigation of these types of resources in other areas of New York, where most development is occurring. If the entire state were subject to BSM rules, then the participation of these resources in the capacity market could decline, potentially threatening New York’s ability to meet its goal of using 70 percent clean energy resources by 2030, which will require a significant build-out of new resources. For example, as part of this goal, New York is committed to deploying 9,000 MW of offshore wind by 2035, which presumably would be located off the coast of Long Island and participate in that regional capacity market. Because renewables of this scale could certainly suppress prices in the capacity market, the NYISO could ultimately adopt similar rules for Long Island, which would significantly limit the participation of offshore wind in the capacity market.

However, even if these rules eventually expand to cover the rest of the state, their practical impacts on the deployment of renewables could be mitigated to some extent if the state moves forward with the carbon pricing proposal in the NYISO’s energy market. The NYISO’s proposal, which was originally introduced in April 2018 and revised in December 2018, would require generators to incorporate a carbon adder equal to the social cost of carbon into their bids in the energy market. As shown in RFF’s modeling of the proposal, the carbon adder would cause energy prices to increase in all zones by an amount that more than offsets the resulting loss in renewable energy credit value in 2025 (the policy drives the REC price to 0 from baseline levels of $2 - $14/MWh [under New York’s clean energy standard prior to the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act], but wholesale energy prices increase by $20-24/MWh). As a result, the policy would reduce the net CONE of new renewables (even with the loss of REC revenue) because the higher energy revenues are netted out from the capacity cost of new entry in the net CONE calculation, making it more likely that these resources would pass the BSM exemption tests outlined above and thus less likely that these resources would be subject to an offer floor and not clear the market.

Carbon pricing in the energy market could therefore be an effective tool for mitigating potential future limits on the participation of new clean resources in the capacity market. If implemented now, before these clean energy goals ramp up, carbon pricing could potentially forestall future changes to market rules that favor incumbent generators over new resources.