New modeling from Resources for the Future shows that accelerating cuts to greenhouse gas emissions in the near future will produce major economic benefits and other long-term positive outcomes.

The 2023 global stocktake from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which will wrap up at this year’s Conference of the Parties (COP28), offers a great chance to not only look back and measure progress toward the Paris Agreement goals but also look ahead and consider the benefits of achieving them. While estimating the economic benefits of achieving Paris Agreement goals is no small task, the RFF-Berkeley Greenhouse Gas Impact Value Estimator (GIVE) model, developed to estimate the social cost of carbon, is a natural tool for the job. In a recent RFF issue brief, we used GIVE to estimate that the benefits of achieving the Paris Agreement targets—both the 1.5°C and “well below” 2°C goals—could amount to hundreds of trillions of dollars when expressed in monetary terms.

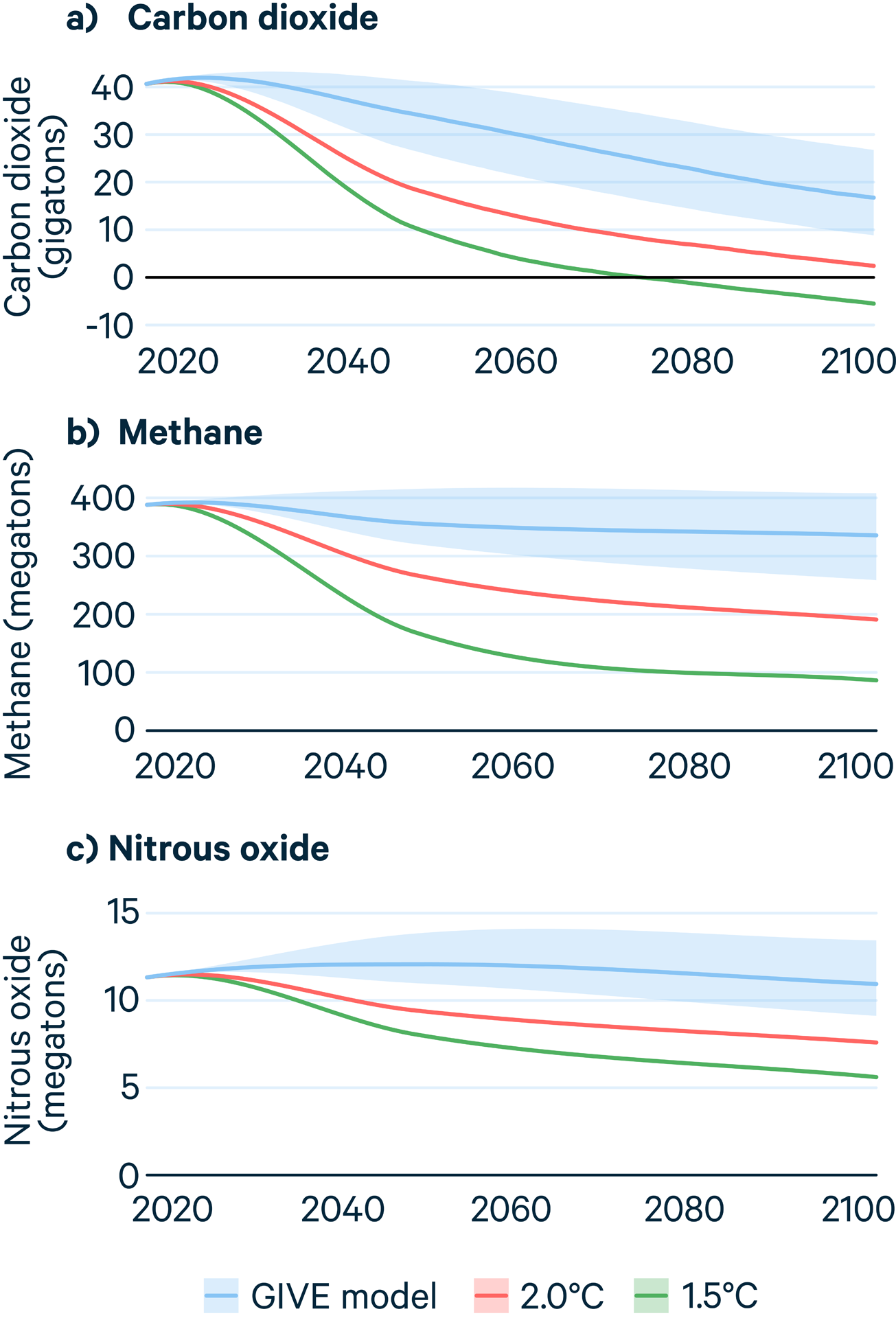

One of the strengths of the GIVE model is the way it considers uncertainty about future greenhouse gas emissions. For carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane, the model includes possible emissions trajectories that range from the most rapid reductions and optimistic net-zero (or even net-negative) greenhouse gas scenarios to what other models often term “business-as-usual” scenarios—or worse. These emissions scenarios lead to a wide range of temperature predictions, with a median or “best guess” falling at about 2.5°C in 2100. We arrived at our estimates of the benefits of reducing emissions by putting a “lid” on our baseline set of emissions trajectories (Figure 1), which we then calibrated to yield temperature pathways that line up with the goals from the Paris Agreement.

Figure 1. Annual Global Net Emissions of Greenhouse Gases from the GIVE Model, Including Pathways for Reaching the 1.5°C and “Well Below” 2°C Paris Agreement Goals

Notes: Solid lines represent median values. Blue shading indicates the 33rd to 67th percentile range. The GIVE model is the RFF-Berkeley Greenhouse Gas Impact Value Estimator model

The central values from the baseline GIVE model suggest a gradual decline in annual carbon dioxide emissions, with the median reaching half of present-day emissions toward the end of the twenty-first century. Annual methane emissions are projected to decline much more slowly, with the median values staying well above 300 megatons per year, and nitrous oxide emissions are not projected to decline meaningfully within the century.

Compare those results to the “well below” 2°C scenario, which approaches net-zero global carbon dioxide emissions by the end of the century, with methane emissions cut in half and nitrous oxide emissions reduced by about a third relative to present-day levels. Also consider the 1.5°C scenario, which reaches net-zero global carbon dioxide emissions before 2080. This more ambitious scenario also cuts annual methane emissions by three-quarters and halves annual nitrous oxide emissions by 2100.

Next, we project what these scenarios mean for global temperature rise through 2100, which the GIVE model handles with a lightweight but well-tested climate model called the Finite Amplitude Impulse Response model. Figure 2 shows these temperature pathways, with the solid lines representing median trajectories and shaded areas spanning the 33rd to 67th percentiles.

Figure 2. Global Surface-Temperature Change Relative to 1850–1900 from the GIVE Model, Including Pathways for Reaching the 1.5°C and “Well Below” 2°C Paris Agreement Goals

Notes: Solid lines represent median values. Shading indicates the 33rd to 67th percentile range. The GIVE model is the RFF-Berkeley Greenhouse Gas Impact Value Estimator model

The baseline GIVE model suggests a central outcome of 2.5°C above preindustrial levels in 2100, with a range of 2.2–2.8°C. The “well below” 2°C scenario rises more gradually, with its median temperature pathway reaching 1.8°C in 2100. Looking at temperatures for the 1.5°C scenario, one notices more of an arc, or an “overshoot.” This overshoot is not surprising, given that present-day temperatures are nearing that threshold, and further temperature increases in the near term are almost inevitable.

However, although temperature rise is likely to exceed the 1.5°C threshold, negative emissions could be deployed to reverse course and meet the goal by 2100, as demonstrated by the negative emissions trajectories in the 1.5°C scenario in Figure 1 and the corresponding declining median temperature trajectory in Figure 2. The median temperature for this pathway returns to 1.5°C by 2100 after peaking above 1.6°C in 2050.

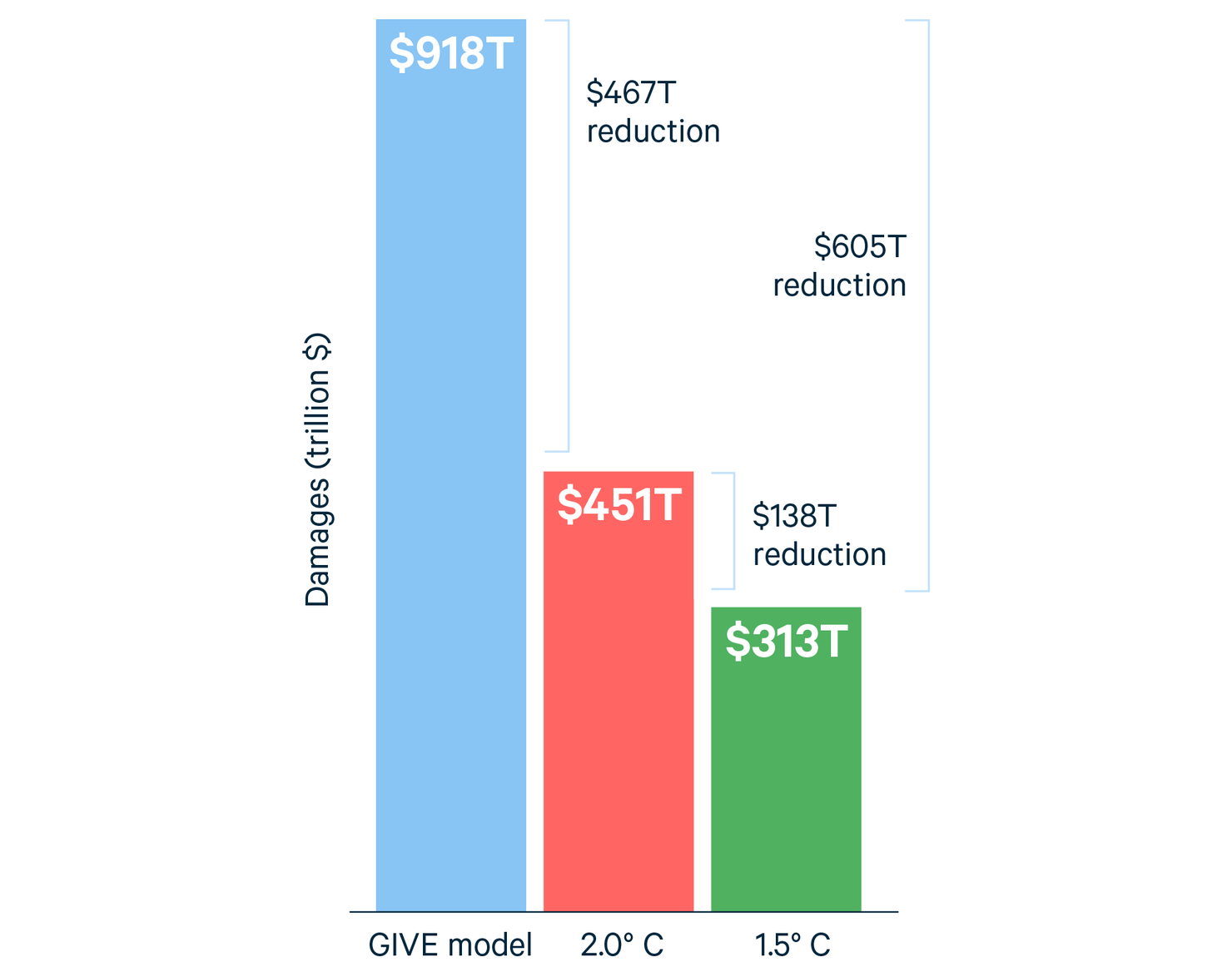

For the baseline GIVE model, more than $900 trillion in expected discounted climate damages are projected to accumulate between 2020 and 2300—the time horizon included in the GIVE model. Although this is a striking figure, the global GDP in 2022 alone was more than $100 trillion. After using a discounting approach that converts uncertain predictions of future economic growth and damages into present-day values, we find that the more than $900 trillion of present-value losses amounts to about 3 percent of present-value GDP over the same time frame. This estimate likely reflects a lower bound because it does not include other climate harms, such as biodiversity loss, decreased labor productivity, and wildfire.

As shown in Figure 3, meeting the “well below” 2°C goal from the Paris Agreement would cut projected climate harms in half to $451 trillion, implying an estimated benefit of $467 trillion for achieving the 2°C Paris Agreement target. Both of those figures are equivalent to about 1.5 percent of present-value GDP. In equivalent annual terms, this $467 trillion figure corresponds to $5.2 trillion in annual benefits. Achieving the more ambitious 1.5°C goal would yield an additional $138 trillion in benefits and limit the damages to about 1 percent of present-value GDP. $138 trillion corresponds to $1.6 trillion in equivalent annual terms.

Figure 3. Cumulative Expected Present Value of Total Climate Damages from the Baseline GIVE Model through 2300, along with Models That Follow the 1.5°C and “Well Below” 2°C Pathways

Estimating the economic harms of climate change is a complex endeavor because the climate affects society at all levels, from individual health to global geopolitics. Even so, a scientifically rigorous understanding of the monetized social benefits of following through on the ambitions of the Paris Agreement will be key to informing climate policy actions. Limiting temperature increases to the Paris Agreement goal of well below 2°C is expected to prevent about half of climate damages—and that’s relative to the GIVE baseline projection of 2.5°C in 2100, which already embodies some arguably optimistic emissions reductions. The benefits relative to business-as-usual scenarios would be even greater; but in either case, our findings demonstrate that accelerating cuts to greenhouse gas emissions in the near future will serve society well for many decades to come.