Introduction by Raymond J. Kopp

Jim Boyd’s Resources article, more than 15 years deep in the magazine archive, aims to demystify the economic valuation of nature to decisionmakers—an ongoing task at Resources for the Future. To many, the question posed by the article’s title, “What’s Nature Worth,” is meaningless. Surely it is the case that the air we breathe and the water we drink are priceless; life on planet Earth could not exist without these natural assets. No economist would argue with that line of reasoning. However, the question Jim poses is not directed at the value of air or water, but rather about the value of a small change in the quality or quantity of air and water. Jim describes these marginal changes in terms of changes to the services that natural assets provide. Marginal improvements in these services are the products of environmental decisionmaking, and the flows of these services determine the efficacy of environmental policies.

Economists face another challenge in communicating the notion of natural asset value. To the economist, value has a very particular meaning and is defined and measured only in terms of humans, i.e., from an anthropocentric perspective. At this point, the economist’s definition of value comes in stark contrast to that of many conservationists who argue for the intrinsic value of natural assets; for example, Anne W. Rea and Wayne R. Munns Jr. say in their 2017 article, “intrinsic value reflects the perspective that nature has value in its own right, independent of human uses”—an ecocentric perspective. Economists are agnostic with respect to intrinsic value; it is concept that simply cannot be measured by economic tools and analysis.

Article by James Boyd

First published in 2004, in Resources no. 154.

What is the value of nature? This difficult question has motivated much of the work done at Resources for the Future (RFF). If it seems odd that such a question could occupy an institution for half a century, considering both the importance and difficulty of the challenge. Nature and the services it provides are significant contributors to human well-being, and society makes decisions every day about whether we will have more or less of it. Knowing nature’s value helps us make those decisions. The difficulty is that nature never comes with a convenient price tag attached. Ecosystems aren’t automobiles, in other words. They are like factories, however. They make beauty, clean air, and clean water, and they feed and house species that are commercially, recreationally, and aesthetically important.

Over the past decades, economic approaches to the “value of nature” question have become ever more sophisticated and accurate. This sophistication has a downside, however: noneconomists rarely understand how estimates are derived and frequently distrust the answers given. To noneconomists, environmental economics presents a set of black boxes, out of which emerges “the value of nature,” such as a statement that “beautiful beach provides $1 million in annual recreation benefits” or "wetlands are worth $125 an acre."

How do economists arrive at such conclusions? For one thing, they examine the choices people make in the real world that are related to nature and infer value from those decisions. For instance, how much more do people spend to live in a scenic area as opposed to a less attractive one? How much time and money do they spend getting to a park or beach? The translation of such real-world choices into a dollar benefit estimate is complicated and requires the use of sophisticated statistical techniques and economic theory.

Problems

Economic valuation is met with skepticism, in part because of the “black boxes” that are used by environmental economists—“black box” being useful shorthand for statistical or theoretical methods that require math or significant data manipulation, the stock-in-trade for economists and some ecologists.

The technical and opaque nature of economic valuation techniques creates a gulf between environmental economists and decisionmakers that fosters distrust. Such studies can also be quite expensive and demand the expertise of a relatively small number of economists trained in ecological valuation. The complexity of the studies undermines the ability of economists to contribute—as they should—to the analysis of priorities, trade-offs, and effective ecological management.

Another criticism of economic valuation is that values are “created” through political and other social processes and are not something that can be simply measured or derived by “objective” experts. Technical analysis—the black box—fosters this criticism because it produces results that can be interpreted and evaluated only by an elite cadre of experts.

Opening the Black Box

RFF’s mission is not only to advance the methodology of environmental economics and other disciplines but also to ensure that its technical research affects policymaking. RFF researchers continue to push the scientific frontiers of ecological valuation and always will. But an additional task is increasingly necessary: communicating to decisionmakers what we as economists and scientists already know and agree upon. As a group, environmental economists need to improve the ways in which they communicate the value of nature.

Unfortunately, better communication involves removing (or at least de-emphasizing) much of the technical content of economic methodology. We economists hate doing this. After all, much of the truth may be lost if the discipline of technical economic analysis is removed. But much of the truth is also lost when economists deliver answers that are not trusted or understood by the real-world audiences we must reach.

Here, I will talk about a method designed to make ecological valuation more intuitive and thereby address some of the criticisms of economic valuation. Working with colleagues at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, we are studying environmental benefit indicators, which are a quantitative, but not monetary, approach to the assessment of habitats and land uses. Environmental benefit indicators strip environmental valuation of much of its technical content, but do so to reach a much wider audience and convey economic reasoning as it is applied to nature. Like purely ecological indicators, environmental benefit indicators summarize and quantify a lot of complex information. And like monetary assessment, environmental benefit indicators employ the principles of economic analysis. Our argument is that indicators can help noneconomists think about trade-offs.

We also believe that indicators can improve the way economists communicate ecological benefits and trade-offs. But it should be emphasized that we do not see indicators as a way to simplify assessment. The value of nature is inherently complex; rarely is there a clear-cut, “right” answer to questions such as which ecosystem is most valuable or which ecosystem service provided by a given habitat is most important.

What Are Indicators?

At the simplest level, indicators can be the number of individuals in a biological community or species present in a habitat. They may also be a measure of the number of days a piece of land is underwater or the presence of nearby invasive species that may threaten an ecosystem. These indicators tell us something about the health of a species or ecosystem.

Organized around basic environmental and economic principles, benefit indicators are a way to illustrate the value of nature. A collection of individual indicators about a given ecosystem can capture the complex relationships among habitats, species, land uses, and human activities, resulting in a more comprehensive picture. Regulators could use indicators to identify locations for ecological restoration that will yield large social benefits, and land trusts could use indicators to identify socially valuable lands for protection. Other applications include the evaluation of damages from oil spills or environmental impact studies.

The techniques we are developing will be relatively affordable and easy to use. Dozens of the indicators we have been collecting are readily available in geospatial data formats. States, agencies, and regional planning institutions increasingly have high-resolution, comprehensive data on land cover and land use, built infrastructure, population and demographics, topography, species, and other data useful for the assessment of benefits.

What Matters the Most?

Indicators should act as legitimate proxies for what we really care about: the value of an ecosystem service. For example, wetlands can improve overall water quality by removing pollutants from groundwater and surface water. This service is valuable, but just how valuable? To answer this question, we can count a variety of things, such as the number of people who drink from wells attached to the same aquifer as the wetland. The more people who drink the water that’s protected by the wetland, the greater the value of the wetland.

But other things matter, as well. For example, is that wetland the only one providing this service, or are others contributing to the aquifer’s quality? The more scarce the wetland, the more valuable it will tend to be. There may also be substitutes for wetland water-quality services provided by other land-cover types such as forests or by human-made filtration systems. Mapping and counting the presence of these other features can further refine an understanding of the benefits being provided by a particular wetland. Does mapping and counting these things give us a dollar-based estimate of the wetland’s value? No. But it does lead to a more sophisticated, nuanced appreciation of the wetland’s value than we would get if we ignored socioeconomic factors and economic principles.

Traditional regulatory and ecological ecosystem assessment techniques typically ignore socioeconomic factors, such as the number of people who benefit from an ecological function. And the techniques never include an assessment of concepts like economic scarcity or the presence of substitutes. These omissions highlight the second important function of benefit indicator systems—they can be used to convey basic economic concepts that speak to value.

Ecosystem Services and Economic Principles

Ecologists and economists have identified a wide variety of very important ecological services, including water-quality improvements, flood protection, pollination for fruit trees, recreation, aesthetic enjoyments, and many others. Indicators should be organized around these specific services to help convey a deeper understanding of the service itself. Also, from both an ecological and economic standpoint, services should be analyzed independently. A typical ecosystem will generate multiple services, but not all services should be assessed using the same data or at the same scale.

The analysis of a service’s scarcity and the importance of substitutes are important economic concepts that can be conveyed. Another is the role of complementary assets, which is particularly important to the assessment of recreational benefits. Access via trails, roads, and docks is often a necessary—or complementary—condition to the enjoyment of recreational and aesthetic services. These things can also be counted and relate intuitively to value.

Finally, an indicator system can also feature proxies for risk to an ecosystem service. For example, an ecosystem service may be threatened by an invasive species that can overwhelm more valuable native species—whether by a rise in sea level if the habitat is in a low-lying area, or by human encroachment if the ecosystem is sensitive to the human footprint. To foster a disciplined communication of results, we are developing indicators for demand, scarcity, substitutes, complementary assets, and risks that are specific to particular services.

How Do Environmental Benefit Indicators Work?

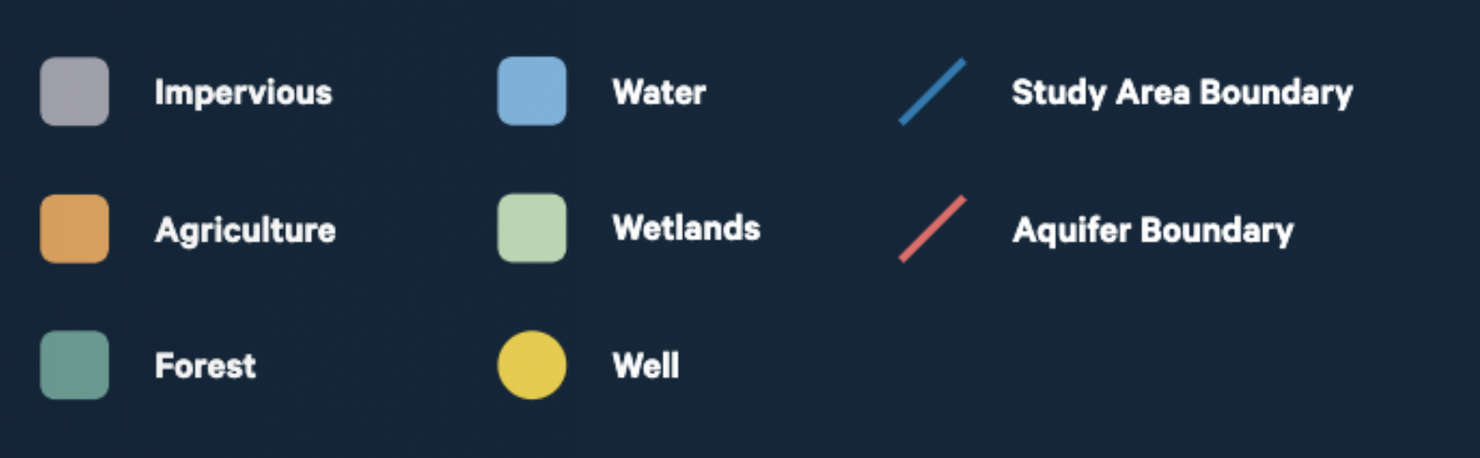

Legend

This figure is rendered from the original image, first published in 2004. The map illustrates how a wetland can contribute to drinking water quality. The wetland in question is hydrologically connected to nearby drinking wells. It is also in an area where wetlands are scarce and where water quality may be impaired by agricultural activity.

Environmental benefit indicators (EBIs) are a way to illustrate the value of nature in a specific setting. An individual EBI might be the presence of invasive species or the number of acres under active cultivation. A collection of indicators about a given area can portray the complex relationships among habitats, species, land uses, and human activities. EBIs are drawn mainly from geospatial data, including satellite imagery. Data can come from state, county, and regional growth; land use or transportation plans; federal and state environmental agencies; private conservancies and nonprofits; and the US Census.

Regulators and planners can use EBIs to address specific questions, such as which wetland site, among many, is the most valuable? Coming up with an effective answer requires looking at many factors: on-site characteristics, such as the type of wetland; off-site characteristics, including the presence of wetlands in the larger area; and socioeconomic indicators, such as the number of people who depend on wells in the area for their drinking water.

The map above graphically portrays how these types of factors may relate to one another in the target area. One of the great virtues of this approach is that unforeseen relationships—such as the amount of A in relation to B—is quickly made apparent.

The Importance of Landscape and Scale

Ecology emphasizes the importance of habitat connectivity and contiguity (or proximity) to the productivity and quality of that habitat. Terms like connectivity and contiguity are inherently spatial and refer to the overall pattern of land uses, surface waters, and topographic characteristics in a given region. Species interdependence and the need for migratory pathways are additional sources of “spatial” phenomena in ecology. The health of an ecosystem cannot be assessed without an understanding of its surroundings.

From an economic standpoint, ecosystem benefits depend on the landscape for an additional reason: because the social and economic landscape affects the value of nature. Where you live, work, travel, and play all affect the value of a particular natural setting. And the consumption of services often occurs over a large scale; examples include recreation and commercial harvests of fish or game, water purification, flood damage reduction, crop pollination, and aesthetic enjoyment.

To ignore or minimize the importance of off-site factors misses much that is central to a complete valuation of benefits. How scarce is the service? What complementary assets, such as trails or docks, exist in the surrounding landscape that enhance the value of a service? These questions relate to the overall landscape setting and are, accordingly, spatial in nature.

What the Audience Wants

Some audiences who are interested in the value of ecosystems crave the answer that’s typically provided by economists: a dollar value. Government agencies are regularly called upon to demonstrate the social value of programs, plans, and rules they oversee. Generally speaking, the higher the level of government, the more demand there is for a bottom-line dollar figure for the costs and benefits of regulations. Such results allow politicians and high-level bureaucrats to wrap themselves in a cloak of legitimacy and objectivity.

Less cynically, putting things in dollar terms makes it easier to analyze trade-offs. The dollar benefit of program A can be directly compared to the dollar benefit of program B. Assuming the dollar figures are correct, we know which program is better, and this is why economists prefer this approach. Only by expressing benefits in a consistent framework can the apples of ecological protection be compared to the oranges of alternative actions.

Conclusion

Environmental economists need to better communicate trade-offs and the value of nature in a way that educates and confers legitimacy on their own economic arguments. Environmental benefit indicators are an underutilized way to do this. Because indicators avoid technical complexity and the expression of value in dollar terms, however, too many economists reflexively dismiss their value. But the alternative—formal econometric benefit analysis—is unlikely to ever generate results that are holistic enough, transparent enough, credible enough, and cheap enough to get widespread practical use. Scientifically sound, econometric analysis should continue to be conducted, of course. But agencies and planners should know that there are alternatives.

Instead of burying the principles of economics in their methodology, economists need to better communicate those principles in ways that resonate with “normal” people. Benefit indicators can help do this by concretely and quantitatively illustrating the relationships that are important to economic analysis. Communicating even a qualitative understanding of economic principles and relationships would be a huge advance for economic thinking in regulatory decision contexts.

Indicators can also be used to track the performance of environmental programs, regulations, and agencies over time—something that gets surprisingly little attention from environmental agencies or economists. To do so would require consistent and large expenditures of time, money, and expertise. But instead of trying to calculate the dollar benefit of a regulatory program over time, agencies could more easily measure things like the number of people who benefit from the ecosystem services that are protected by the programs. This type of measurement doesn’t yield a dollar benefit, but it does yield an intuitive number that conveys valuable information.

Given these benefits, indicators are underutilized in local, regional, and executive-level environmental decisionmaking.