After the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) revised its assessment of a rule that limits mercury emissions and other pollutants from power plants, RFF Senior Fellow Karen Palmer and other economists convened as an independent review committee and released their own findings. In this Q&A, Palmer shares why she and the group of researchers banded together to offer their own analysis, and how EPA’s new assessment downplays significant positive aspects of the rule.

In 2012, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards rule (MATS), which limits emissions of mercury and other toxic air pollutants from power plants. An early regulatory impact analysis conducted by EPA valued the benefits of MATS at $33 billion to $90 billion per year, compared to an annual cost of $9.6 billion.

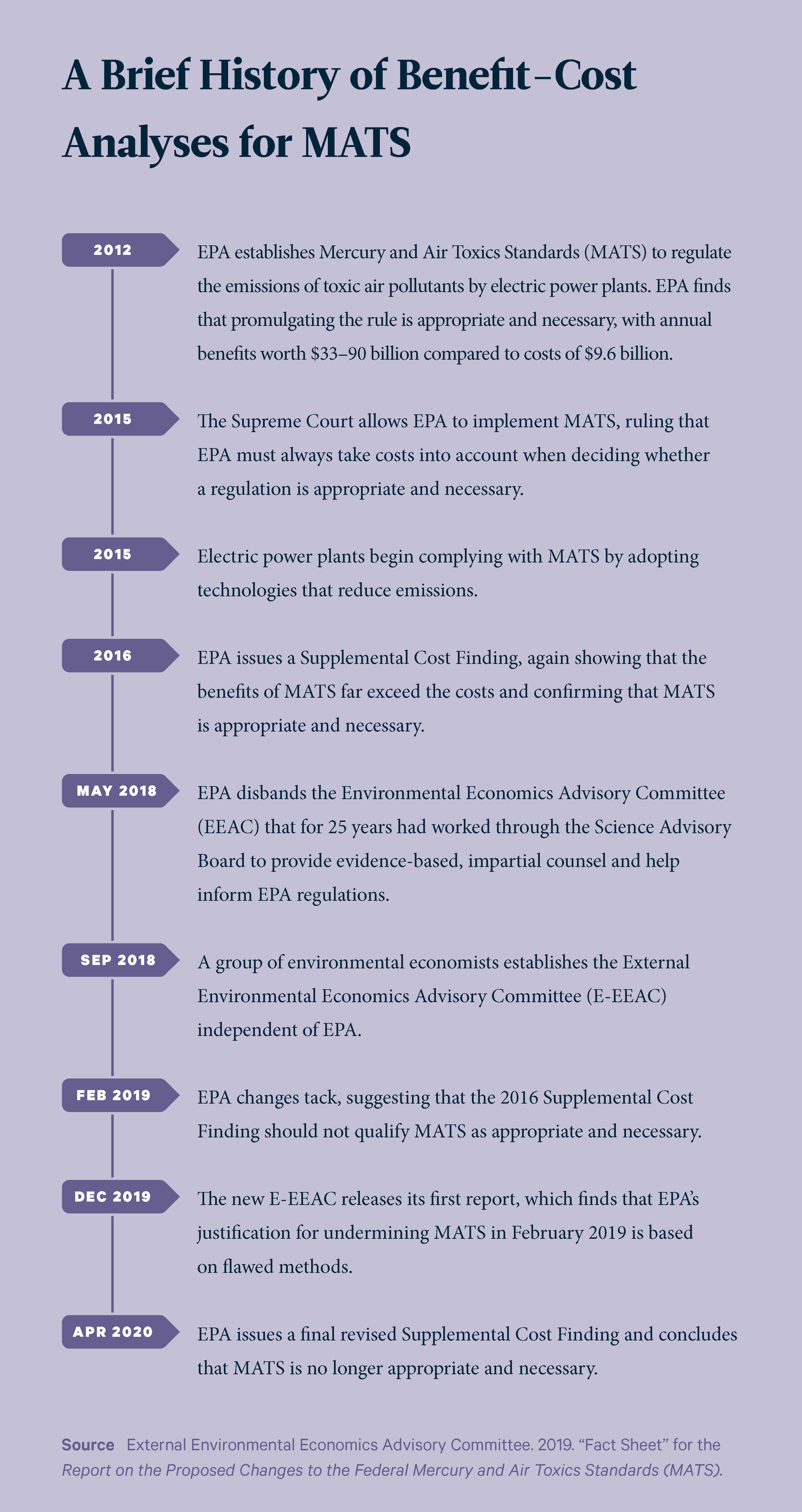

Since then—and after an additional EPA assessment in 2016 concluded that the benefits of MATS far outweigh its costs—EPA revisited MATS in early 2019, reevaluating the findings of its prior analysis and reaching the opposite conclusion: that the costs of the regulation exceed its benefits. The agency’s new analysis suggested that MATS is no longer appropriate and necessary, although EPA opted not to repeal the regulation outright. In April 2020, EPA issued a final revised Supplemental Cost Finding, concluding that MATS is no longer appropriate and necessary.

Just prior to all this, in 2018, EPA dissolved its long-running Environmental Economics Advisory Committee (EEAC), which had served EPA’s Science Advisory Board for 25 years. Stepping into this vacuum, an independent group of economists formed a new External Environmental Economics Advisory Committee (E-EEAC), which aims to restore the original function of the EEAC and provide evidence-based, nonpartisan, timely counsel about EPA regulations. The E-EEAC produced its first report this year, which focuses on MATS and EPA’s new proposal from 2019. Among the report’s authors are Resources for the Future (RFF) Senior Fellow Karen Palmer, along with RFF University Fellow and review committee co-chair Joseph E. Aldy.

The E-EEAC report finds that EPA’s 2019 MATS proposal is flawed, for three major reasons: EPA’s new proposal does not follow federally prescribed best practices for benefit-cost analysis because it neglects to include co-benefits; underestimates the benefits of mercury reductions; and does not account for significant, unexpected changes in the power sector.

Resources magazine spoke with Palmer, the director of the Future of Power Initiative at RFF, to ask for more details about the unexpected changes in the power sector and what all of this means for the future of MATS.

Resources magazine: Can you describe what activity in the EPA motivated the E-EEAC to take on this work?

Karen Palmer: The main motivation came from EPA’s treatment of co-benefits in the recent proposal related to the MATS rule. In the new proposal, EPA claims that co-benefits from reductions in pollutants that are not directly targeted by MATS should not be considered. EPA now says that only direct benefits should be weighed among the benefits and costs. In the original regulatory impact analysis, most of the quantified benefits from MATS came from reductions in those other pollutants that constitute co-benefits—largely emissions of nitrogen oxide (NOₓ) and sulfur dioxide (SO₂) that transform into fine particulates. Ignoring these co-benefits tips the balance in the benefit-cost analysis of the rule. EPA is now arguing that it wasn’t appropriate and necessary to issue the regulations in the first place, although the agency hasn’t gone so far as to propose retracting the rule.

In most air pollution regulations, balancing costs and benefits is not supposed to play a role in setting regulatory requirements relevant to clean air. That’s because the Clean Air Act (CAA) generally requires that regulations reduce air pollution to a level that both protects human health with a margin of safety and protects the welfare of society.

But mercury is regulated under section 112 of the CAA, which does allow for balancing benefits and costs in setting standards. So, the outcomes of benefit-cost analysis can be particularly relevant in this context.

An early regulatory impact analysis conducted by EPA valued the benefits of MATS at $33 billion to $90 billion per year, compared to an annual cost of $9.6 billion.

Another issue with EPA’s reevaluation is that MATS has been in place for a while, and electricity-generating firms already have spent large amounts of money to comply, including some capital investments. Some of these costs are sunk and can’t be undone. But the electric power industry also has changed in some unexpected ways since EPA’s original regulatory impact analysis, and those changes should be reflected in any effort to review the regulation from today’s vantage point.

We wanted to address all these issues with our analysis.

How do EPA’s recent estimates for the benefits and costs of MATS in 2019 compare to the regulatory impact analyses that they applied to MATS in the past?

EPA’s 2019 proposal was a revision to the Supplemental Cost Finding issued by the Agency in 2016. The only real difference between the prior analyses in 2016 and in 2011 and this proposed revision in 2019 is that the new proposal dismisses the co-benefits of MATS—in other words, the pollution reductions beyond mercury and air toxics that are likely to result from compliance with the regulation.

Other than that, the analysis is unchanged—despite important changes in our understanding of the environmental and health impacts of mercury, and important changes in the electricity sector itself. We discuss all of this in our report.

Because the new proposal from EPA stays unchanged outside of eliminating important co-benefits, the agency implies that the costs from the earlier analysis still apply and are potentially avoidable, if the regulation would be undone in the future. But—and this is important—power plants have been in compliance since 2016, and some firms made major investments to come into compliance. A lot of the costs associated with controlling these emissions are capital costs—essentially sunk costs, and thus not avoidable if the regulation were repealed.

We find in our analysis that the actual compliance expenses for power plants were less capital intensive than EPA thought, when EPA was trying to project how firms were going to comply with the regulation—so, sunk costs are less than EPA anticipated they would be, but those costs are still highly relevant. If you were to take the flip-side view of this and say that the rule is not appropriate and necessary, and if we would go to the next step and undo the MATS regulation, then what would be the benefits? Well, the benefits would be the costs foregone, but the firms have already made a lot of investments, and those costs—they’re not going to be undone. The only costs that would actually be avoided would be any operating costs associated with the pollution controls that are already in place.

Thus, the costs represented in that 2011 report (and EPA’s 2019 report) overstate both total cost and avoidable costs, were the regulation to be undone.

It’s important to recognize, too, that the size of the coal-fired generation fleet has gotten smaller. So, the emissions reductions from the rule also are probably overstated.

The report emphasizes that EPA’s 2019 analysis fails to account for changes in the power sector that deviate from prior predictions. What effect do changes in the power sector have on clean air, in general?

There has been a steady decline in SO₂ emissions from electricity generators (Figure 1) due to a combination of factors.

The biggest effect on major pollution from the electricity sector (including SO₂, NOₓ, and CO₂) comes from the fact that less electricity is being generated with coal—dramatically less than what was typical, historically—and more electricity is being generated by natural gas and renewables.

Figure 1. Changes in SO₂ Emissions from Electric Generating Units

Probably one of the biggest factors influencing that shift is the reduction in natural gas prices resulting from the advent of fracking and the development of horizontal drilling, which together created the ability to extract abundant natural gas resources at low cost. When gas prices came way down, the electricity sector’s investment in gas-fired generators went up, and the dispatch of the systems shifted away from coal, to gas.

Gas has no SO₂ emissions associated with it; it has substantially lower NOₓ emissions; and it has roughly half the emissions of CO₂ per megawatt hour than coal does.

In recent years, we’ve also seen policies that encourage renewables and declines in the costs of renewables, including wind and solar. So, those are starting to grow; we’re in the early stages there. And those two technologies have no emissions associated with them.

This changing composition of electricity production is having a big effect. Also, when you look at old EPA forecasts of how electricity would be produced in the future, and then compare that with what actually happened, electricity demand has not grown as fast as expected. As a matter of fact, it’s been pretty flat for the last decade or so—much below the growth in demand that people were expecting.

All these factors are contributing to emissions reductions.

How much has MATS itself influenced the electricity sector?

One thing we wanted to know is how many of the retirements of coal-fired power plants are due to MATS, and we looked at two different studies.

One was by RFF colleagues Joshua Linn and Kristen McCormack (who was a research assistant at RFF at the time). They developed an economic model of the electricity sector and looked at the effects of various economic factors and environmental regulations on the retirement of coal plants. They found that something like five gigawatts of coal plant retirements (which is a really small fraction) were due to the MATS rule. A lot of the retirements that have happened in the intervening years have been largely attributed to the fact that natural gas is cheaper. The substantial amount is due to that—generators and electric utilities are opting to use more natural gas and less coal. A small fraction is due to the fact that electricity demand didn’t grow as fast as people expected, back at the beginning of the decade. So, there’s just a small fraction of retirements that are attributable to MATS, according to their analysis.

Using completely different methods, they found a very similar result: that roughly five gigawatts of coal were retired due to the MATS rules.

Another study was done by some folks at Harvard—James Stock and Todd Gerarden (when he was a student there). They focused on the effects of market forces and regulation on the coal mining industry and coal production. And they similarly found in their decomposition analysis that most of the effects were coming from reduced prices of natural gas. And, using completely different methods, they found a very similar result: that roughly five gigawatts of coal were retired due to the MATS rules.

Those two analyses didn’t really focus on emissions so much, but they came to pretty similar conclusions about the effects of the rule, in the end, being fairly small, because the sector is changing so much as a consequence of other market forces.

How does EPA’s latest evaluation of the MATS-related benefits and costs bear out in terms of how mercury affects public health?

Most of the benefits really come from the co-benefits. But EPA’s recent analysis focuses on the mercury-related benefits, and it only looks at one pathway of mercury benefits that EPA was able to quantify in the original regulatory impact analysis from 2011: the effect on children’s IQ of eating fish that are caught by recreational anglers. So, not commercial fisheries, but people fishing and then serving caught fish to their children, which exposes children to mercury and to potential negative IQ effects.

I’m not saying this is all completely settled—it’s still an evolving area of epidemiology and science—but at the time, there was even more uncertainty about what the health impacts were of reduced mercury exposure and ingestion. Some more recent studies have suggested that reducing mercury emissions creates previously unknown benefits, in terms of other pathways of mercury exposure, such as fish caught through other means, like commercial fishing—and that cardiovascular effects are likely much bigger than the neurological effects.

Some more recent studies have suggested that reducing mercury emissions creates previously unknown benefits... and that cardiovascular effects are likely much bigger than the neurological effects.

The studies that have looked at the health effects of mercury haven’t looked in particular at the MATS-related emissions changes. So, you can’t apply the numbers directly to the health benefits of reduced mercury ingestion based on MATS implementation, but you could say that there’s a substantial unrecognized benefit that merits further attention by EPA.

And, of course, our committee was composed of economists—not epidemiologists. I’d say there needs to be more epidemiological work in conjunction with economics to flesh out what we know about the health benefits more fully. But I still do think there is enough new work that EPA could have taken their estimate of the health benefits further in the recent reevaluation.

What kind of impact do you hope the report will have?

I hope it will keep the agency focused on doing state-of-the-art ex ante benefit-cost analyses of regulatory proposals, and even push the envelope on that as science progresses. I hope it will show policymakers at EPA the value that independent analysis and adherence to best practices can bring to regulatory decisionmaking at the agency. I hope it will reemphasize the importance of including a comprehensive assessment of all benefits and costs in future EPA regulations.

I also hope it gives some insight into the types of lessons that might be possible with more concerted ex post analyses of existing regulations. Congress acknowledged the importance of bringing evidence of the impacts of past policies to bear on policy decisions going forward, when it passed the Evidence-Based Policymaking Commission Act of 2016 and the subsequent act in 2018. These acts established protocols for data collection and ex post analysis of policy effectiveness to the extent possible across federal agencies.

I hope EPA will look at our recommendations when implementing benefit-cost analyses going forward—that’s what we hope.

And what kind of impact do you think the report is likely to have?

That’s really hard to say. I think in the long run, it could have a substantial impact. In the short run, say the next year and a half—it’s hard to say.

When I served on the EEAC with EPA years ago, the primary focus of our efforts at that time was on ex post benefit-cost analysis, which continues to be challenging. The agency has a mandate under a series of executive orders to conduct ex ante regulatory impact analyses for all major environmental regulations. But a lot can be learned from doing ex post reviews—going back and looking at what happened, and how it differed from our expectations, and why—which can inform the development of new regulations. It’s possible that academics, or other people who want to inform better policymaking in the future, would pick up on the importance of ex post analyses. I guess that’s the hope of the coauthors of this E-EEAC report.

Environmental policymaking is a process that unfolds and evolves over time, and it would be good to learn from experiences as much as possible, so that we can improve the next rounds of the process.