The vast majority of federal funding for flood risk reduction is appropriated after disasters strike. Allocating a greater share to pre-flood programs could improve the effectiveness of federal spending.

Over 90 percent of federal dollars for flood risk reduction is appropriated to flood-damaged areas in the aftermath of a disaster through off-budget, supplemental legislation. Very little money for risk reduction is available before floods occur. This current approach has some upsides. It can often be more cost-effective to incorporate risk reduction into repair and rebuilding than to try to upgrade undamaged buildings and infrastructure. And there is some indication that households and communities are often not interested in risk reduction on sunny days, and that targeting risk reduction dollars in the aftermath of a flood provides funds when the risk is salient.

But there are also downsides. First, this model targets risk reduction funds haphazardly where a flood has occurred—instead of spending dollars in areas with the greatest risk, on the most cost-effective investments, or to provide benefits for the most people or for those who most need the assistance. Second, sending very large amounts of funds to state and local governments, expecting them to create entirely new programs that use those funds wisely in the chaos of recovery is probably not realistic. Reports of fraud and abuse plague this type of spending. Finally, funds appropriated for disasters in supplemental legislation typically escape the normal scrutiny and analysis. Before a disaster hits, there is time for careful planning and program development. In a recent paper in the journal Water Economics and Policy, we examine the spending patterns of federal programs to reduce flood risks and discuss whether a new approach is warranted.

Many flood risk reduction programs exist across multiple federal agencies but only a few account for the vast majority of spending—namely, programs housed in the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the US Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps), and the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

FEMA has three primary grant programs for funding flood risk reduction: the Pre-Disaster Mitigation Grant Program, the Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program, and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. Of these, the first two are pre-disaster programs. The Pre-Disaster Mitigation program, which also funds risk reduction efforts for other hazards, requires a 10–25 percent local cost share and covers projects such as building retrofits and the relocation of structures out of flood-prone areas. Between 2002 and 2014, 2013 saw the lowest appropriated amount for flood projects, at $2.1 million, and 2005 the highest, at $141.8 million (2015$). Across those years, the average appropriation of funds specifically for flood-related projects was $46.2 million.

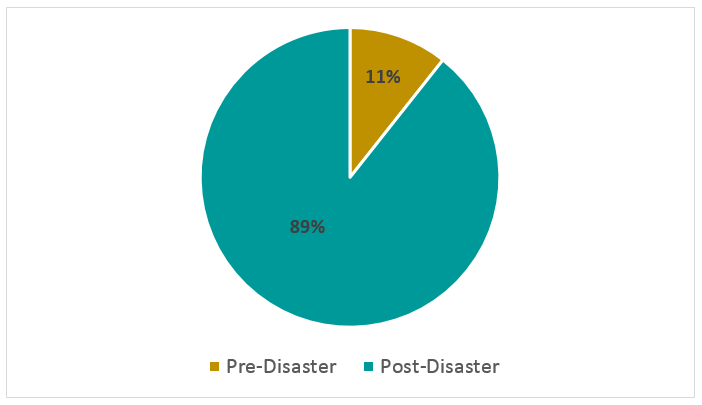

From 2002–2014, post-disaster spending made up almost 90% of FEMA’s overall spending on flood risk reduction.

Author

The Flood Mitigation Assistance program was created to reduce flood insurance claims to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Grants are available to participating communities (of which there are 22,000 nationwide, covering almost all areas of flood risk in the United States) for mitigation measures on properties that have flood insurance. The grants cover projects such as elevation, relocation, and flood-proofing that will result in reduced NFIP claims, and are funded through flood insurance premium revenue. Priority is given to properties that have seen repeated flood-related claims. (Before 2012, FEMA also had two grant programs targeting repetitive loss and severe repetitive loss properties under the NFIP, but those were merged into the Flood Mitigation Assistance program in 2012.) Between 2002 and 2013, the program’s average annual spending was $28.5 million, but funding in 2014 was $115 million (this higher amount may be due to the inclusion of the other two programs).

Funds for reducing flood risk after a disaster are provided through FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. Through this program, a set percentage of total disaster assistance funding is dedicated to risk reduction. Projects include property acquisition and conversion to open space, elevation, and localized flood control, among other activities. Spending under the program on flood-related events exceeded FEMA’s pre-disaster spending on flood risk reduction in all years except one between 2002 and 2014—with outlays up to 25 times greater. The years with the highest spending were 2005 ($3.8 billion), 2008 ($2 billion), and 2012 ($2.1 billion). The lowest amount was spent in 2014 ($55 million). Across these years, post-disaster spending on flood risk reduction represented almost 90 percent of the agency’s overall spending on flood risk reduction (Figure 1).

Figure 1. FEMA Spending on Flood Risk Reduction, 2002–2014

Chart represents funding for flood-related projects under FEMA’s Pre-Disaster Mitigation Grant Program, the Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program (including the two programs targeting repetitive loss and severe repetitive loss properties merged into it in 2012), and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

Where flood control planning and infrastructure are concerned, the US Army Corps of Engineers’ budget makes up the majority of federal spending. Corps flood risk reduction projects provide funding for levees, flood walls, and river channelization, as well also covering flood warning systems, flood-proofing, elevation, dune creation, and relocation out of a floodplain. Local governments are responsible for paying a share of the construction costs for levees and channels and also for all future costs for operations and maintenance. Spending by the Corps on these projects was three times greater in the 1960s than it is today—in 2010, $554 million was appropriated for these projects.

The Corps also has a smaller, pre-flood program, Floodplain Management Services, which provides information, technical services, and planning support to other agencies. Annual appropriations for this program are in the $5–10 million range. After a flood, the Corps Emergency Management Program, funded through supplemental appropriations, helps communities return to pre-flood conditions. Although most of the funds are used for repair, they are sometimes spent on incorporating risk reduction measures into projects. Appropriations for this program totaled $11.5 billion between 2005 and 2010.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development provides another significant source of federal funding for flood risk reduction. In the aftermath of large disasters, Congress typically appropriates funding to the Community Development Block Grant–Disaster Relief Program. This program does not have annual appropriations; it only receives funds from supplemental legislation. Local governments have enormous flexibility in how they spend these dollars, though they must submit an action plan to the agency for approval. Some funding will be used for immediate recovery and for repair and rebuilding. Local governments vary in how much they use for risk reduction, or “building back better.” Data is not available to assess how much federal funding is spent in these different categories.

The nation has spent billions on flood risk reduction programs—but primarily after disasters.

Author

Across these three agencies, the overwhelming majority of federal dollars for flood risk reduction is typically provided through off-budget spending in supplemental appropriations after presidential disaster declarations. There are pros and cons to a funding model that adds flood risk reduction spending to post-disaster recovery. We see an opportunity to improve the effectiveness of federal spending for flood risk reduction. This would first recognize that, over recent decades, the nation has spent billions on flood risk reduction programs—but primarily after disasters. These funds could be usefully redirected into annual spending. For example, Congress could annually appropriate into ongoing risk reduction programs the average spent between 2000 and the present on risk reduction spending in post-disaster supplemental legislation. This new annual spending would require the receiving agencies to target those dollars at the riskiest areas and the most cost-effective projects, and to report to Congress each year. In this new model, Congress would limit post-flood spending to immediate recovery needs and to risk reduction measures that can be shown to cost-effectively be incorporated into rebuilding.