Climate policy aims to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, but another important outcome from decarbonization is improved air quality. New research from a team lead by Resources for the Future and the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance asks the question: Will disadvantaged communities see benefits?

Decarbonization and environmental protection often are discussed as interchangeable and completely aligned policy goals. In many ways, this equivalence makes sense, as many strategies for cutting greenhouse gas emissions also reduce conventional air pollutants, and vice versa. What often gets lost, though, is that some policies that aim to reduce greenhouse gases can increase air pollution at the local scale because of how the policies apply differently across space. For instance, the dramatic electrification of vehicles may increase demand for natural gas on the power grid, which can contribute to local air pollution in vulnerable communities near gas power plants. Understandably, analysis of climate policy often focuses on the core goal of reducing carbon emissions—but an equally important body of work investigates what’s referred to as “ancillary benefits” such as improvements in air quality.

These ancillary benefits are particularly important for advocates in the environmental justice movement. Historically unjust systems and policies have led to neighborhoods in which low-income communities and communities of color bear disproportionate burdens from air pollution. In recent decades, advocates have been putting community concerns at the center of discussions about decarbonization, and the federal government and many state governments have resolved to meet their own respective climate goals while improving air quality conditions in disadvantaged communities.

This increased focus on community protection creates a pressing need for analysis that not only looks at the net benefits of a policy, but also offers more granular estimates of how specific communities will be impacted. For example, instead of estimating merely that a policy will increase electric vehicle adoption by 50 percent, new studies also can ask, Where are those vehicles deployed? How does the changing technology mix impact air quality in different areas? Do subsidies lead to disproportionate improvements in wealthy areas, while pollution remains high in disadvantaged communities? To answer these questions, we’ll need detailed spatial information about the location of disadvantaged communities, behavioral models with detailed demographic information, and advanced air-quality modeling that can process location-specific emissions changes and predict how emissions will migrate and chemically interact to form harmful air pollution.

To answer these critical questions, Resources for the Future and the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, along with researchers at Yale, UC Davis, and Northeastern University, have partnered to investigate local air-quality impacts on disadvantaged communities due to the implementation of the New York Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. Specifically, we compared two different sets of policies to a business-as-usual case projected for 2030, both in line with the statutory requirements of the law, but that differ in their ambition and the degree to which they focus on aiding disadvantaged communities. One policy case (the scenario inspired by the Climate Action Council) models what the New York State government may implement, which includes policies that have been discussed in other jurisdictions and proposed by New York policymakers. The other (the stakeholder case) was crafted by a team led by the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and included many environmental and climate justice advocates in New York, who prioritized community protection and directing benefits to marginalized communities. We modeled the impact of policies on the electric power, on-road transportation, port, and residential building sectors; the effects of these policies on emissions of direct fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) and precursors to PM2.5 (nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and volatile organic compounds); and the resulting PM2.5 concentrations experienced by disadvantaged communities and non-disadvantaged communities alike.

Our analysis has revealed several key insights.

Insight 01

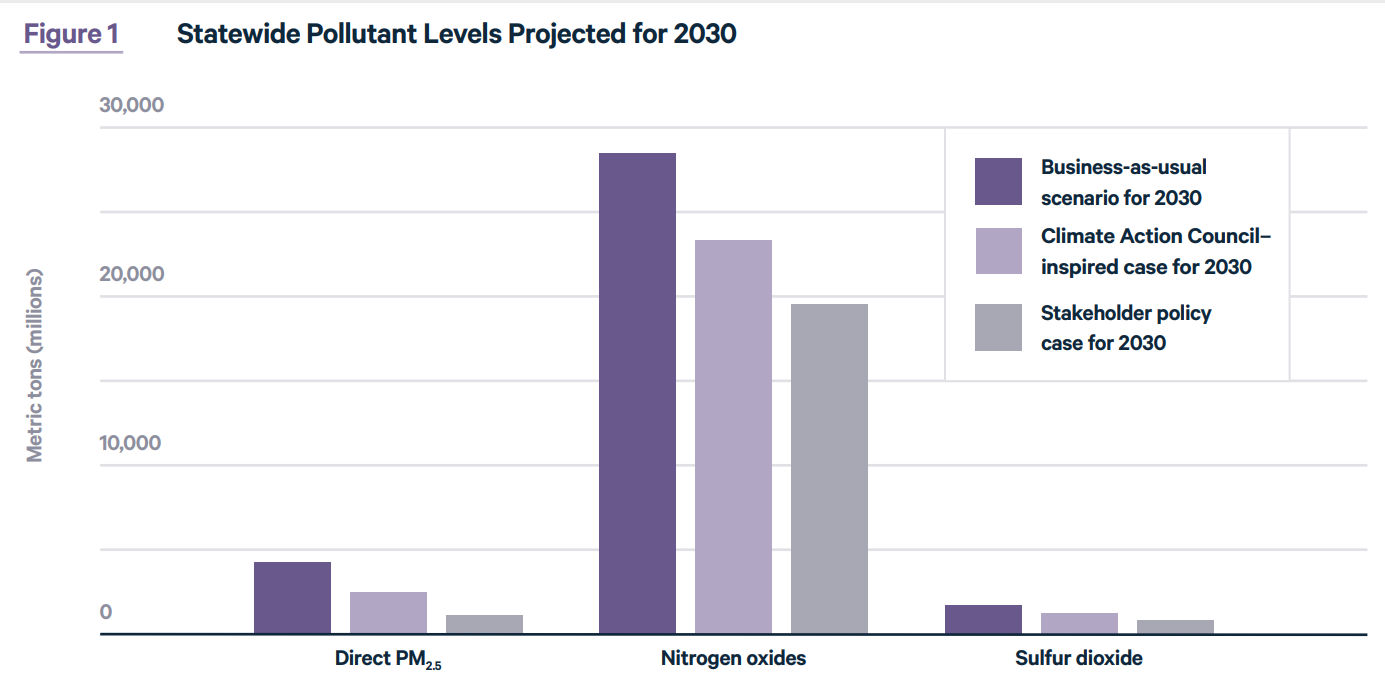

Greenhouse gas reductions in 2030 are substantial under both cases relative to the business-as-usual case, but are greater under the stakeholder case than under the Climate Action Council–inspired case (58 percent reduction versus 34 percent reduction, respectively). The stakeholder case also leads to greater statewide emissions reductions for pollutants that contribute to poor air quality (direct PM2.5, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and volatile organic compounds) than the Climate Action Council–inspired case (Figure 1).

Insight 02

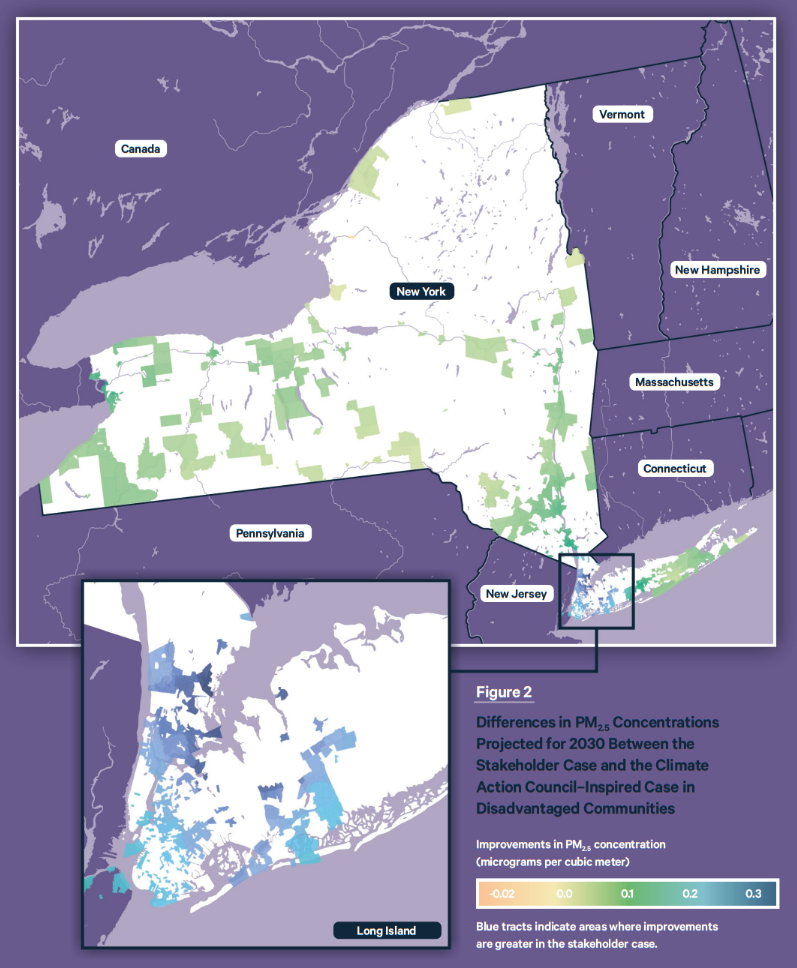

The stakeholder case leads to greater statewide air-quality improvements (as measured by PM2.5 concentration reductions) than the Climate Action Council–inspired case. In the stakeholder case, air quality improvements in disadvantaged communities are greater than the improvements in non-disadvantaged communities (Figure 2). In the Climate Action Council–inspired case, statewide average air-quality improvements in disadvantaged communities are comparable to the improvements made in non-disadvantaged communities.

Insight 03

On average across New York State, both policy cases improve air quality (in terms of reductions in PM2.5 concentrations); however, some census tracts do experience a worsening of air quality (increases in PM2.5 concentrations). In the Climate Action Council–inspired case, about 6 percent of the roughly 5,000 New York tracts (296 tracts) experience worse air quality, one-fourth (75 tracts) of which are disadvantaged communities. In the stakeholder case, only 3 census tracts experience worse air quality, none of which are disadvantaged communities.

Insight 04

The most vulnerable communities in New York State (the top 10 percent of tracts in the state’s social vulnerability measure, and the 10 percent with the worst air quality historically) experience pronounced improvements under the stakeholder case.

Insight 05

Because air-quality improvements are associated with public health benefits, the greater improvements in the stakeholder case would yield the greatest public health benefits. Furthermore, because elderly Black New Yorkers are particularly vulnerable to health complications related to PM2.5 exposure, this demographic group would experience disproportionate improvements in mortality risk relative to their Hispanic, Asian, and white counterparts (Table 1). We did not do a complete health-impact analysis, but in an illustrative calculation, we find that, while 22 percent of the New York City population aged 65+ is Black, this group accounts for 42 percent of the avoided deaths from PM2.5 reductions compared to white residents (who make up 41 percent of the New York City population aged 65+, but account for 37 percent of the avoided deaths).

Insight 06

The greater improvements in the stakeholder case occur because environmental justice stakeholders prioritized more stringent policies than the policies that were included in the Climate Action Council–inspired case. In most cases, policies that reduce greenhouse gases also reduce co-pollutants that contribute to poor air quality. Key policy drivers of the greater improvements in the stakeholder case include the following: a higher price on carbon and co-pollutants, more generous subsidies for heat pumps targeted at low-income households, and stricter phaseouts of fossil fuels in the electricity and residential sectors. While these more effective policies require higher levels of investment, a full cost-benefit analysis was outside the scope of this work. Previous regulatory analyses that evaluate the stringency of policies which aim to mitigate greenhouse gases and air pollution often find that the environmental and health benefits of added stringency often outweigh the costs; however, such an analysis was not performed for this project.

We see through our work that ambitious climate policies can yield the greatest impact on climate change mitigation and air-quality improvement across all communities. Our research offers unique insights into the air-quality impacts that differ among communities in New York State due to choices surrounding the implementation of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act in 2019. Our study provides a framework for evaluating future policies that could impact the magnitude and location of changes in emissions through addressing economic behavior, alongside methods that can be useful in evaluating how disadvantaged communities in particular will be affected. We’ve learned a lot, and we’re still in the early stages; work in this field presents many opportunities for future research.