Distinguished by tiny yellow flowers that bloom each spring, the Scotch broom seemed a natural addition to Thomas Jefferson’s exotic private garden. One of America’s earliest horticulturists, Jefferson imported many of his plants from outside the continent—but this shrub’s influence would prove unusually enduring. Native to Europe, the Scotch broom now extends as far west as California. It has caused millions of dollars in damage, displacing native plants and releasing seeds that are toxic to livestock.

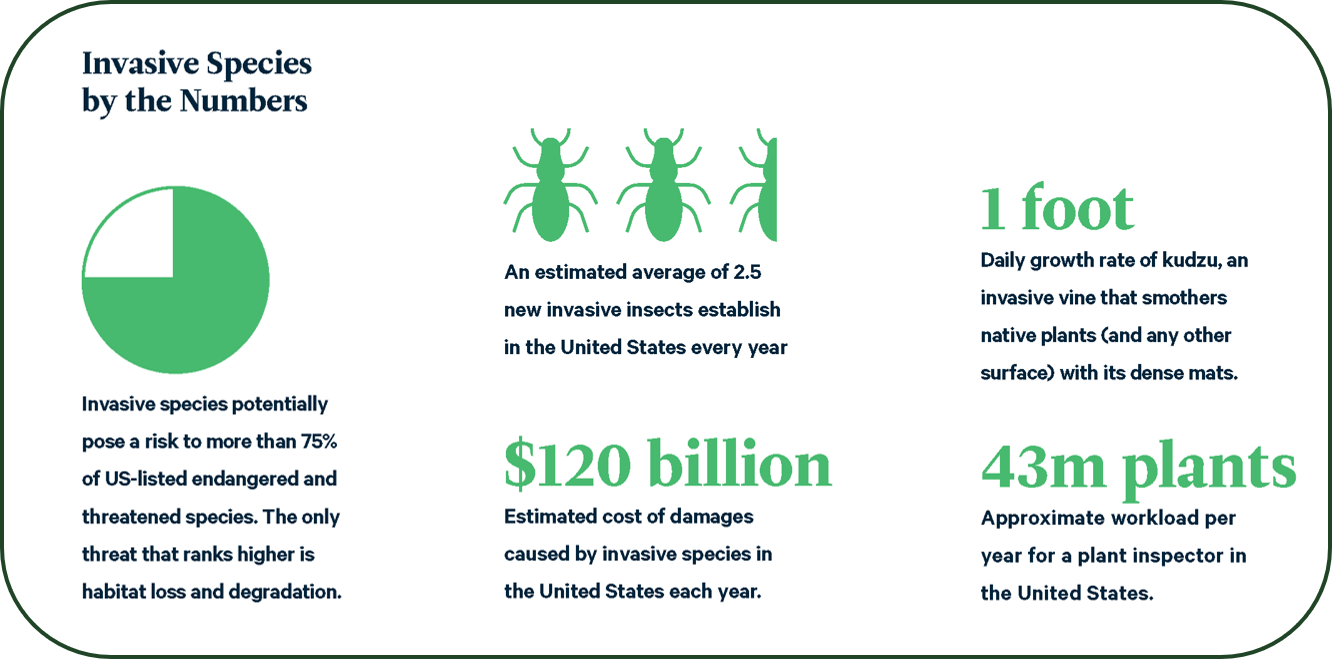

That a Founding Father might be responsible for introducing an invasive species to the continent neatly encapsulates how central plant imports have been to America’s development and how easy it is for nonnative species to wreak havoc in a new land. The economic benefits of the global plant trade are varied: most plants currently used across the agriculture, forestry, and horticultural industries were originally imported. But the consequences of invasive species like the Scotch broom can be stark. “Invasive species disrupt agriculture and other managed landscapes, they cause loss of ecosystem services, and they can either cause or help to spread disease,” says Michael Springborn, an associate professor at the University of California, Davis. One widely cited study out of Cornell University estimates that invasive species can run up recurring damages of $120 billion annually.

The international plant trade still creates opportunities for invasive plants to thrive, but the trickier challenge nowadays is invasive insects and plant diseases, which can hitch rides on plant shipments sent to America and more easily evade detection than a rogue shrub. “Live plant imports have historically been a primary pathway for invasive pest introduction. They’re the perfect place for insects or diseases to come into the country, because the pests are riding on their host material,” explains Dr. Rebecca Epanchin-Niell, a fellow at Resources for the Future (RFF) who closely studies invasive pests. “You’re trying to keep the plants alive, so therefore, you’re also helping keep the pests alive as they come in.”

Research conducted by Epanchin-Niell and Springborn, along with a working group of experts supported by the University of Maryland’s National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC), is helping to inform a recent policy shift in how the US government inspects plant imports. Based on years of research and collaboration, their proposed policy solution works within established regulatory frameworks but allocates existing resources in a novel way, ultimately incentivizing plant producers to keep pests out.

Lay of the Land

While pest-infested plants represent only a tiny proportion of all shipments that enter the United States, one study, whose authors include some members of the SESYNC working group, affirms that infested plant shipments have passed through US ports undetected in spite of the risk mitigation policies that had been in place in 2009. Another study estimates that, even as inspection and other biosecurity policies have improved over the decades, an average of 2.5 new species of invasive insects establish in the United States every year.

Regulations governing the spread of plant species have existed since at least the 1700s, but since the introduction of the Plant Protection Act in 2000, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has had sole discretion over inspecting plant imports. For many years, the agency employed a model that instructed inspectors to examine about two percent of each arriving shipment. In effect, this approach led to oversampling large shipments and undersampling small ones. “[APHIS] recognized that this might not be the most efficient strategy, both because it was an inconsistent means for gathering information, but also because it equally targeted low- and high-risk material,” Epanchin-Niell says.

So, in 2011, the agency publicly indicated that it was looking to implement a “risk-based sampling and inspection approach” for managing plant imports. This would involve two major shifts: APHIS would inspect different amounts of each shipment depending on the shipment’s size, and APHIS also would prioritize the inspection of shipments that were deemed to be a higher risk. Epanchin-Niell and Springborn answered the call to devise the optimal policy—one applicable to the nation’s needs and one that was possible, given the resources available to APHIS. A major problem: there was no scholarly consensus as to which type of risk-based model would be ideal, especially given the immensity of the global plant trade.

Hatching a Plan

Instead of setting out to develop a brand new solution, Epanchin-Niell and the other researchers first looked to other countries for guidance, but the ways in which different leading economies inspect incoming plants and record data vary wildly. A very restrictive policy—like New Zealand’s system, where most imported plants have to be quarantined and observed before being allowed entry—would slow down a booming trade and require more resources than APHIS has available. Conversely, a too lax policy might make it easier for nonnative pests to invade local ecosystems.

The central challenge that Epanchin-Niell and Springborn faced was the seeming inevitability of new pests escaping detection, especially as government resources failed to match the rate of new imports. An estimated five billion plants enter the United States every year, and that number has grown precipitously over recent decades. All those plants go through one of just 16 plant inspection stations, from Guam to New Jersey to Puerto Rico, where inspectors look for impossibly small damages or discolorations in impossibly large plant shipments. One study estimates that the average workload for an APHIS inspector in 2010 was 43 million plants per inspector per year.

Ideally, the optimal inspection model would keep pests out; gather information about the risk posed by different exporters; and, to reduce the burden on inspectors, create incentives for producers to hold themselves to higher standards.

Altering producer behavior was the most necessary goal of a new inspection model—and simultaneously the most vexing. “Perhaps most importantly, inspections [should] motivate exporters to try to keep their shipments clean,” Springborn says. “No exporter wants their shipment stopped at the border, nor do they want to become flagged as a higher risk worthy of greater inspection intensity in the future.”

The collaborators at SESYNC were able to estimate the economic impact of three major invasive pests in North America, compare importation policies and best practices across a variety of countries, and eventually propose a risk-based inspection model that is applicable to American needs and regulatory frameworks.

“The goal of the research was both to provide some empirical and theoretical support for how shifting to [a risk-based] policy could improve outcomes, and also to figure out how to implement that policy, for it to be most effective,” Epanchin-Niell says.

Making Moves

Ultimately, their proposed solution was nominally straightforward: separate producers into one high-risk group and one low-risk group. Exporters with a history of good behavior and low interception rates would face less scrutiny in future shipments, while exporters whose shipments contained pests more often would be subject to a more intensive screening. Rather than devoting resources equally to all producers, more would be devoted to those that posed the greater risk. Based on their analysis, 20 percent fewer infested shipments would enter the United States if APHIS enacted the suggested policy—with no increase in funding or resources required.

The most surprising part of this research to Epanchin-Niell was “the magnitude to which the behavior response [to the risk groups] affects the anticipated rate of introduction of pests.” Essentially, producers designated to the high-risk group have obvious reason to put more effort into ensuring their plant shipments are uninfected, because better performance means a chance to move into the quicker low-risk inspection group. But those producers designated as low risk have reason to adjust their behavior, too: so they can remain in the expedient inspection group and avoid more burdensome inspection procedures. A simple designation encourages all kinds of producers to improve their behavior, whereas a uniform inspection model—where good behavior is not rewarded, and bad behavior isn’t punished—provides a much weaker incentive for improvement.

“The response of the low-risk exporters is what’s neat. Even though they enjoy a lower inspection rate, they still have a very strong incentive to stay clean, because they don’t want to risk falling into the high-risk group. Economists call this ‘enforcement leverage,’” Springborn says.

Informed in part by the research of Epanchin-Niell and Springborn, APHIS is in the process of implementing significant changes to its inspection model. It has already moved away from the uniform two percent model in favor of a risk-based sampling system, which prompts inspectors to examine more than two percent of small shipments and less than two percent of larger shipments. The agency has yet to fully implement the more substantial policy shift of splitting producers into low- and high-risk groups, but APHIS has signaled it is moving in that direction. Understandably, rolling out a comprehensive policy shift across APHIS’s 16 inspection sites, gathering enough evidence to gauge the relative risk posed by thousands of international plant producers, and applying enough enforcement to meaningfully alter behavior will take time.

Once the new rules are fully enacted, little will appear to change, at least to the average consumer who buys a garden shrub or looks out over the landscape. If a plant inspection policy is working, the ecosystem around us ideally grows undisturbed. But the consequences of a malfunctioning inspection system might become more noticeable: new pests invade forests, ravage ecosystems, and spread more quickly than humans can stop them. The value of a revamped plant inspection policy is, in part, the assurance that the plants we use to structure our lives, that have been central to American life for decades and more, will keep growing.