A major retrospective analysis of the Clean Air Act reveals its many public health benefits, along with its associated costs.

In the same year that saw the founding of Earth Day and the creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), President Nixon signed into law the Clean Air Act of 1970 (CAA) on December 31, ushering in what is arguably the most important and far-reaching environmental statute enacted in the United States.

This legislation shifted the state-oriented focus of most air quality regulation to the federal government, under the purview of the newly created EPA. It stimulated a broad-based and costly effort to limit major air pollutants across the United States, with specific targets and timetables for action. It also empowered citizens to sue the government when it failed to perform its duties.

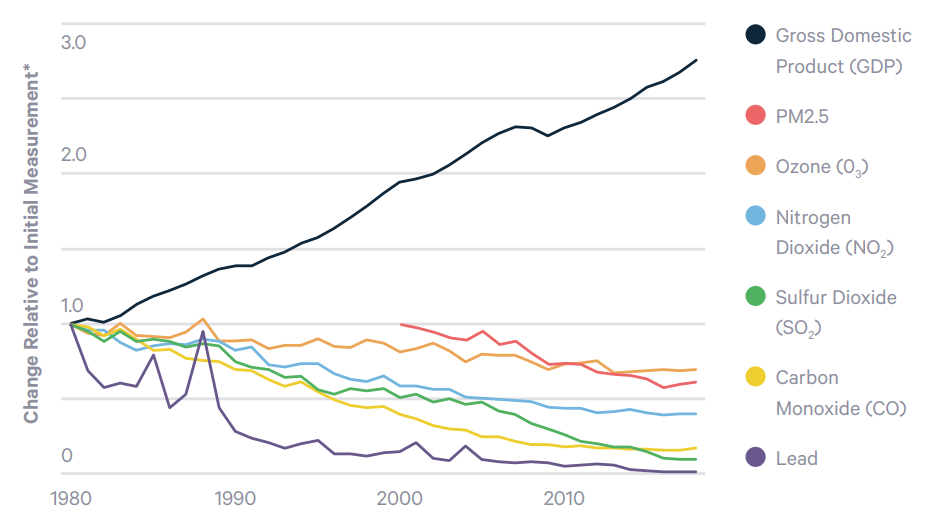

In the 50 years since the passage of the CAA, air pollution has dropped dramatically, even as gross domestic product has quadrupled (Figure 1). To better understand the CAA’s role in the notable improvements in air quality, we have looked at retrospective studies of federal air quality rules, drawing insights on the environmental, economic, and public health impacts of the CAA. Areas of focus include the effects of geographically differentiated standards, the performance of cap-and-trade policies and technology standards, and the responses to regulation in imperfectly competitive markets.

Figure 1. Change in Gross Domestic Product and Six Common Air Pollutants, 1980–2018

One important takeaway from these studies is that a key feature of the CAA—the imposition of more stringent regulations where air quality is poorer—has sometimes resulted in more rapid air quality improvements in those areas, but at substantial cost to local economies.

We also find that cap-and-trade programs have delivered greater emissions reductions at lower cost than conventional regulatory mandates, but policy practice has fallen short of the ideal.

Finally, our review of the literature has provided information about two categories of benefits—lower medical expenditures and human capital gains—not previously associated with improvements in air quality in US regulatory impact analyses (the forward-looking assessments of a regulation’s expected impacts).

The Evolution of the Clean Air Act

By the middle of the twentieth century, a number of alarming smog episodes in US cities and industrial areas had raised public awareness about deteriorating air quality. In perhaps the most extreme case, a lethal smog enveloped the manufacturing town of Donora, Pennsylvania, in October 1948, making thousands sick and killing at least 20 people over the course of just five days. Hundreds of New Yorkers died in a smog episode in November 1953, and the following year in Los Angeles, heavy smog shut down industry and schools for most of October.

The federal government responded by enacting a series of air pollution bills, culminating in the Clean Air Act of 1970. Fundamental provisions of this law required the following:

- EPA to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for six major air pollutants: carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen oxide (NOₓ), ozone, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide (SO₂). The CAA requires periodic review of these standards, and EPA has revised the NAAQS for several categories of pollutants over the years in response to the latest public health research.

- States to submit state implementation plans to EPA, which demonstrate how they intend to meet the standards.

- EPA to set uniform national emissions standards for new cars and light trucks. The law prescribed an ambitious 90 percent reduction in hydrocarbon, carbon monoxide, and NOₓ emissions by 1975 via these standards.

- All steel plants, oil refineries, and other major industrial facilities built after 1970 to meet technology-based standards, dubbed “new source performance standards.”

In 1977, the CAA was amended, primarily to address the problems major metropolitan areas were facing in achieving attainment with the NAAQS, especially ozone pollution standards. The amendments also imposed updated technology-based new source performance standards, which required that new and modified power plants achieve a 90 percent reduction in SO₂ emissions.

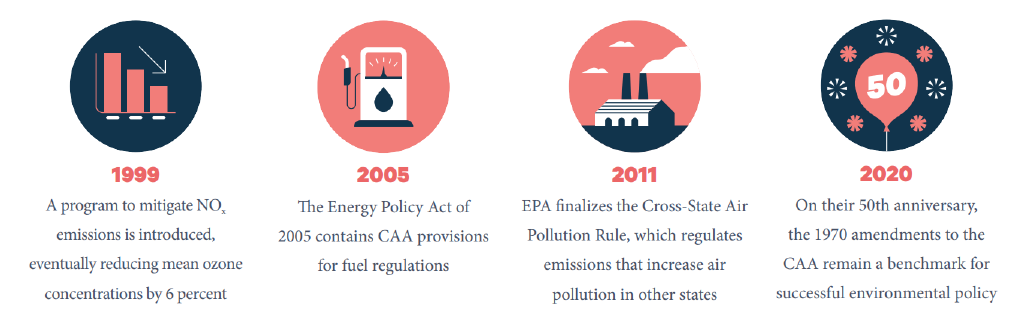

The CAA was amended again in 1990, representing a significant expansion of air quality regulation. The law authorized EPA to ban lead in fuel completely, the culmination of a two-decade phasedown of leaded gasoline. Further reductions in chlorofluorocarbons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons in refrigerants were also authorized, as was a new round of emissions standards for cars and light-duty trucks. The 1990 amendments also included new provisions to address acid rain, by introducing a cap-and-trade program to reduce SO₂ emissions. During the 1990s, state and local governments implemented regional cap-and-trade programs, including the NOₓ Budget Trading Program and Southern California’s Regional Clean Air Incentives Market program (RECLAIM), to make progress in attaining ozone and SO₂ NAAQS.

Congress subsequently has amended specific provisions of the CAA through appropriations riders or as a part of other legislative initiatives. For example, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 contains CAA provisions for fuel regulations, including the Renewable Fuel Standard (revised in 2007) and state boutique fuel programs. Other administrative initiatives include the development of cross-state programs to limit SO₂ and NOₓ emissions from power plants, which rendered the 1990 acid rain provisions largely superfluous, along with regulations to address carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions.

Evaluating the Performance of the CAA

EPA routinely projects the potential effects of major rules (such as expected benefits and costs) to inform regulatory decisions, by preparing regulatory impact analyses. While these analyses draw on a now-extensive literature covering the atmospheric chemistry, epidemiology, and economics of air pollution, the analyses by definition forecast the future, rather than evaluate what happened in practice.

As we reflect on the 50th anniversary of the 1970 Clean Air Act, we’ve asked what we can learn about the law’s causal economic, environmental, and public health impacts. Thanks to considerable advances in empirical economic research over the past two decades, existing retrospective studies use rigorous methods to study the effectiveness of regulations in achieving stated benefits and costs, along with any unintended consequences, often expressed as adverse economic impacts. A common approach is to look at two groups—one affected by a regulation and one not—and compare them before and after the regulation is implemented. For example, many studies compare counties that are in compliance with the NAAQS (so-called attainment counties) with nonattainment counties that have been subject to more stringent regulation.

The largest number of papers we’ve reviewed speak to the impacts of spatially differentiated regulations. We use those papers to ask: What are the costs of imposing more stringent standards in nonattainment areas, and what are the benefits?

The CAA is also notable for promoting market-based cap-and-trade policies to reduce emissions. A significant portion of the retrospective literature is devoted to analyzing the performance of pollution allowance markets in the real world. Other papers examine the unanticipated consequences or failures of regulations to reduce emissions, including situations in which a regulation had no impact on ambient air quality.

Finally, the literature has provided information about categories of benefits—lower medical expenditures and human capital gains—that have not been previously associated with improvements in air quality in regulatory impact analyses.

The Performance of Standards Based on Attainment Status

An important feature of the CAA is that it originally required states to impose more stringent regulations on counties with nonattainment status under NAAQS. The 1977 amendments authorized adoption of stronger, direct emissions standards on industrial plants located in nonattainment areas. As a result, we would expect air quality to improve more in nonattainment counties than in attainment counties.

This hypothesis has been tested for three air pollutants (ozone, particulate matter, and SO₂), using nonattainment status per the 1977 and 1990 CAA amendments. In all cases, at least some evidence over some periods shows that air pollution declined more rapidly in nonattainment counties—and at monitors that were out of attainment, regardless of location.

At the same time, research suggests that imposing tougher standards in nonattainment areas has led to fewer plant openings, lower employment, and losses in earnings for high-emitting industries, relative to attainment counties. For example, a 10-year study of pollution status and employment in four states—Illinois, Maryland, Washington, and Wisconsin—suggests that employment in newly regulated plants was approximately 15 percent lower in 2000 than in 1990, and that earnings over a nine-year period were 20 percent lower than pre-regulation earnings.

These results raise several questions for future study: Were the adjustment costs imposed on nonattainment counties by the CAA justified by the additional air quality improvements in these counties? What would have been the impact of imposing equally stringent standards on stationary sources in attainment counties? Could some of the adverse impacts on workers have been mitigated through a program that provides financial and professional support, similar to Trade Adjustment Assistance?

The Performance of Cap-and-Trade Programs

The CAA has been responsible for launching a national cap-and-trade program to reduce SO₂ emissions (the SO₂ allowance program), regional programs to address NOₓ (the NOₓ Budget Trading Program in the eastern part of the country), and Southern California’s RECLAIM program. EPA designed a market for renewable fuel credits to implement the Renewable Fuel Standard.

The SO₂ allowance program has been widely heralded as the triumph of market-based instruments over command and control and was predicted to lead to large cost savings, compared to imposing a uniform performance standard on electric utilities. However, while the literature we review suggests that the program has indeed led to cost savings compared to a uniform performance standard, those savings are not as large as predicted ex ante. These lower cost savings are partly due to the decision of some utilities to install scrubbers rather than purchase allowances and/or switch to low-sulfur coal—a choice that is estimated to have increased annual compliance costs by nearly $100 million. Evidence also suggests that some of the potential cost savings were appropriated by railroads, which set relatively higher prices for transporting low-sulfur coal to Midwestern power plants.

Another important issue involves the impact of allowance markets on the distribution of damages. In the SO₂ market, the main purchasers of allowances were eastern power plants, which were located in more densely populated areas than most of the sellers, which in turn were located in more sparsely populated areas west of the Mississippi River. No evidence exists to suggest that the allowance program has led to more health damages than a uniform emissions standard; however, the evidence is mixed for the impact of the RECLAIM program on “hotspots,” or local areas with higher emissions and associated damages.

In the 50 years since the passage of the CAA, air pollution has dropped dramatically, even as gross domestic product has quadrupled.

The literature also has documented situations in which allowance market design could be improved. In the case of the market for renewable fuel credits—which refiners were required to produce to meet the Renewable Fuel Standard—annual (rather than multi-year) announcements by EPA of refiners’ compliance obligations led to considerable uncertainty and volatility in the price of credits. Announcing renewable fuel mandates several years in advance, as was done under the SO₂ and NOₓ Budget Trading Programs, would have helped the market function more effectively.

In addition to allowance trading, another method of reducing compliance costs is to allow firms flexibility in meeting regulatory standards, rather than prescribe a technology standard. However, in the case of reformulated gasoline, evidence indicates that flexible federal regulations that gave refiners latitude to choose which volatile chemicals to remove from gasoline were not effective in reducing ozone levels. Refiners chose the cheapest option—removing butane, which is less reactive than other volatiles. In contrast, more prescriptive rules issued by the California Air Resources Board did yield measurable benefits from the regulated gasoline in the California market.

Unexpected Benefits of the CAA

The economic literature on the CAA also reveals instances in which a program delivered a larger set of benefits than anticipated when it was designed. The NOₓ Budget Trading Program and regulation of particulate matter by establishing NAAQS offer two examples.

Efforts to employ a cap-and-trade program to reduce NOₓ in the eastern United States have resulted in an estimated 40 percent reduction in NOₓ emissions during the summer months for sources in the states covered by the program. This NOₓ reduction translates into declines of about 6 percent in mean ozone concentrations and 35 percent in the number of high-ozone days during the summer months.

The significant reductions in emissions and ozone concentrations in the covered states have contributed to substantial public health benefits, including greater-than-estimated reductions in ozone-related deaths (about 2,000 fewer individuals). Evidence also suggests that the program reduced medical expenditures—which had not previously been quantified as a category of benefits in air pollution regulatory impact analyses—by about $800 million per year.

More than any other pollutant regulated under the CAA, particulate matter has been linked in the epidemiological literature to premature mortality and morbidity. Exposure to particulate pollution in utero or during the first year of life also has been shown to have potentially lifelong effects, including on lung, heart, and brain development.

A 2017 study used nonattainment status under the 1970 CAA to examine how this early exposure impacts earnings and labor force participation later in life, focusing on ages 29–31. The researchers estimate that a 10 percent reduction in exposure to particulate matter during the first year of life increases the quarters worked by 0.7 percent and mean annual earnings by about 1 percent. Although these human capital impacts are small, they affect a large exposed population.

Taken together, these benefits represent a significant and potentially large category of benefits not previously considered in regulatory impact analyses of air pollution regulations.

Toward a Comprehensive Analysis of the CAA

The CAA has delivered clear success stories—removing lead from gasoline, phasing out chlorofluorocarbons and other substances that deplete the stratospheric ozone layer, and dramatically reducing sulfur emissions from power plants and transportation fuels. Emissions of air toxics also have declined substantially. These actions over the past 50 years beg the question of regulatory performance evaluation: What have been the causal economic, environmental, and public health impacts of the CAA? Fortunately, economic research on environmental regulation has progressed substantially in the past two decades and delivers at least partial answers to this important question.

Ideally, a retrospective analysis of the CAA would involve a comprehensive assessment of the law’s contribution to observed air quality improvements, along with associated changes in human health and welfare. Such an analysis would focus on the realized benefits and costs of major regulations, and it would consider the role of economic incentive mechanisms in achieving emissions reductions. It would also consider the unintended (adverse or beneficial) consequences and distributional impacts. It would account for the impact of CAA rules and the distributional impacts of the rules. In short: a tall order.

Our review is best understood as a launching point toward a comprehensive retrospective assessment of the CAA. But evidence pointing to a larger set of benefits than expected—along with a number of unintended consequences of CAA rules—provides a compelling argument for continued study.