An equitable transition to a low-emissions economy will require difficult decisions about which policies can best achieve multiple goals. In the years ahead, policymakers will seek to find policies that can serve three masters in addition to reducing emissions: supporting jobs, reducing inequities, and limiting policy costs.

Clean energy is surging in the United States and around the world. With rapid cost declines and support from public policies, technologies such as wind, solar, and battery storage have been ramping up to provide larger proportions of energy globally. As policymakers look to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants from our energy system, clean sources will almost inevitably take center stage.

But what are the economic, employment, and equity implications of ramping up these technologies, especially compared to the incumbent sources they seek to displace? Will the number, type, and quality of jobs created by the growth of clean energy match those lost in coal, oil, and natural gas—and is that even the most useful question to ask? What has research told us about the cost-effectiveness of existing clean-energy deployment policies, and how do these policies stack up against alternatives? Can clean energy policies address the legacy of energy and environmental injustice that stretches back for decades?

For some of these questions, the answers are clear. But for others, new research is needed to inform future policymaking.

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs

Earlier this year, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden said: “When I think about climate change, the word I think of is ‘jobs.’” At the same time, President Donald Trump has criticized his opponent, warning of fossil energy job losses in key swing states such as Pennsylvania.

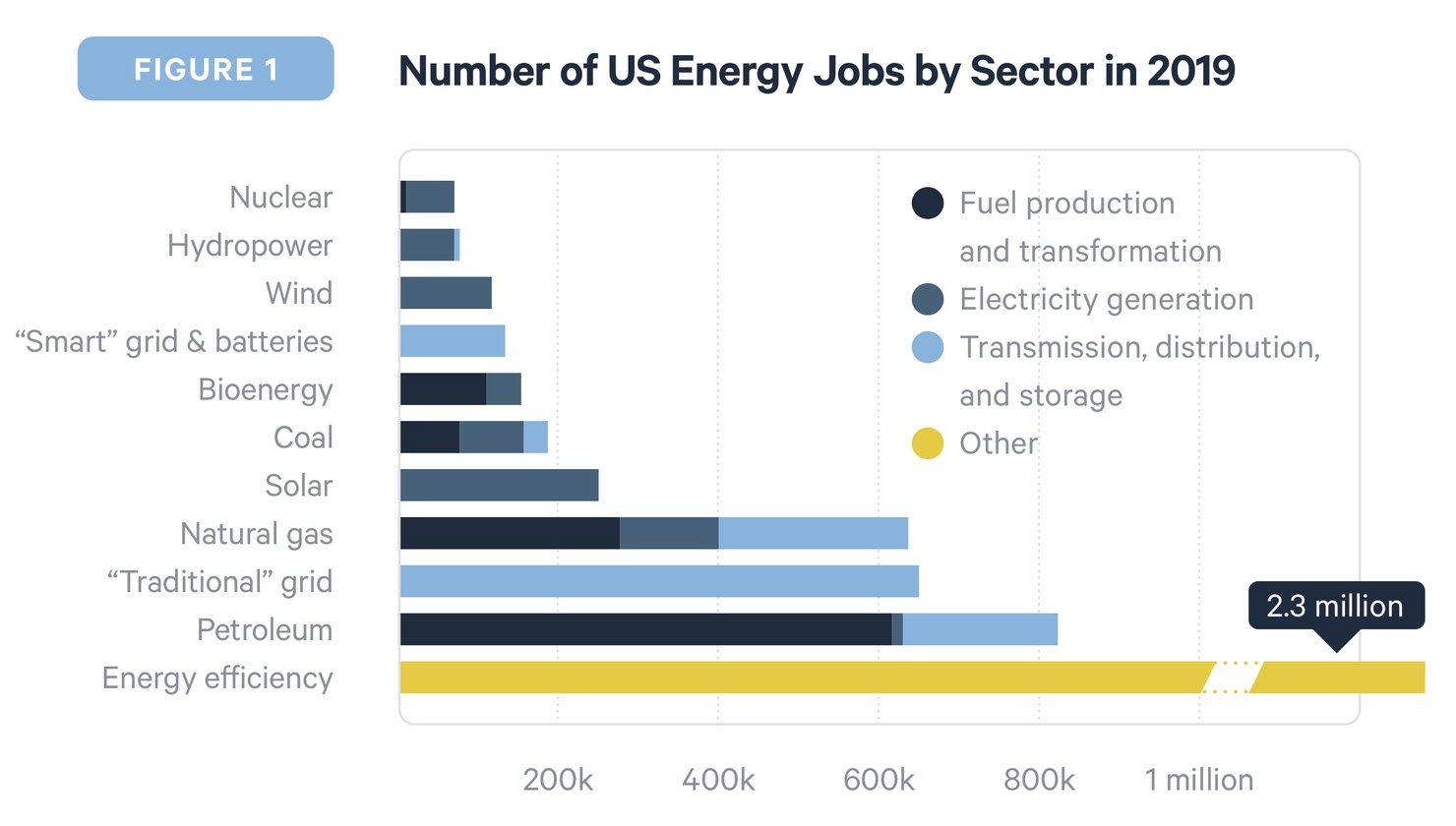

With such a clear focus on jobs, it’s worth considering the state of play on energy employment in the United States. COVID-19 has upended the economy—energy included—but data from 2019 can help us understand some fundamentals. Jobs in fossil fuels (which include energy extraction, processing, transportation, storage, and end uses for electricity and transportation) totaled more than 1.6 million, led by oil (822,000), natural gas (634,000), and coal (186,000). These figures lag behind the 2.3 million Americans working in energy efficiency (e.g., home weatherization, energy-efficient appliance manufacturing) but considerably exceed the nearly 500,000 Americans working in solar (248,000), wind (115,000), and nuclear (70,000) energy.

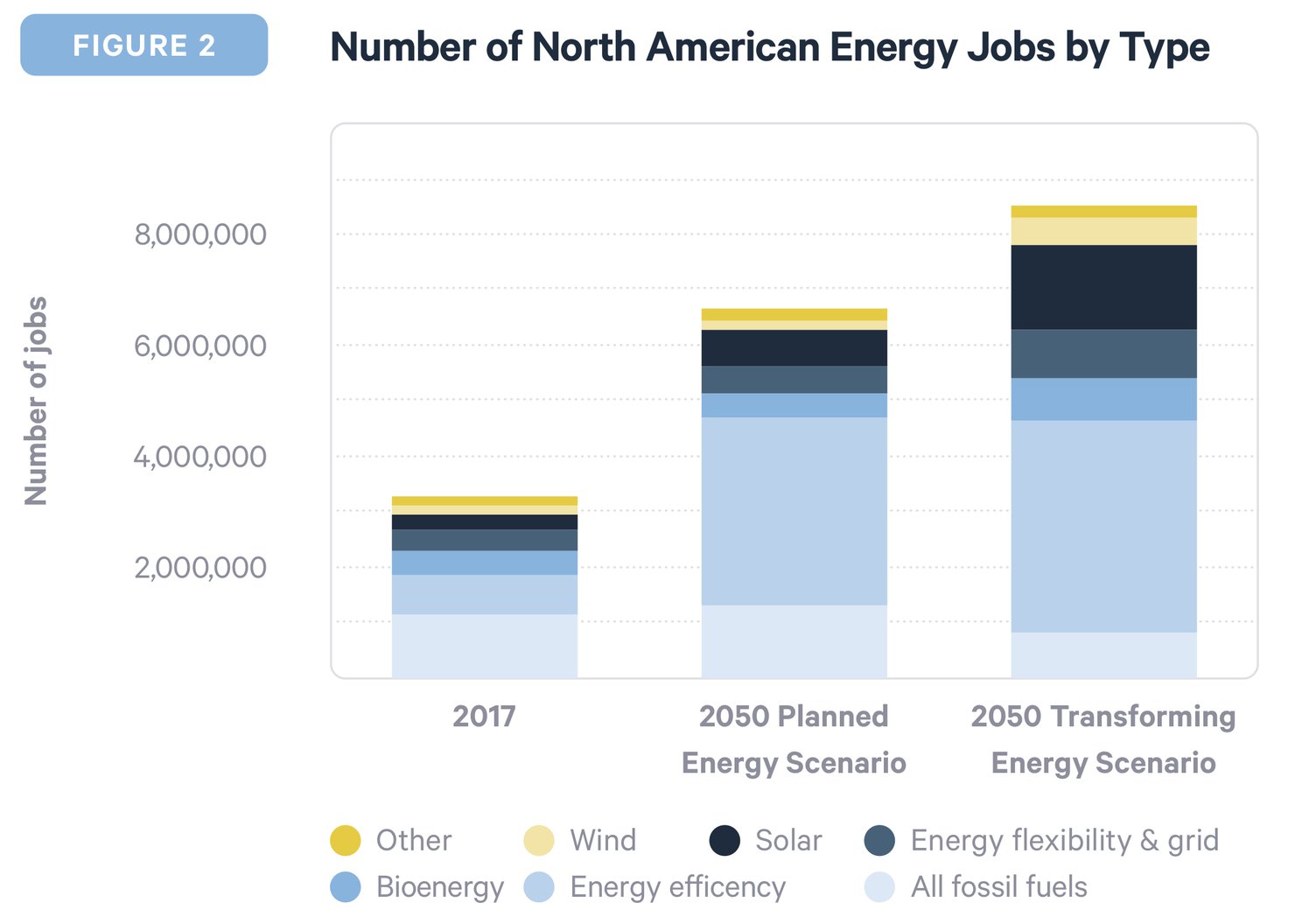

How might this distribution of jobs change in the context of an energy transition? Several recent analyses by Fragkos and Paroussos (2018), Mercure et al. (2018), and Montt et al. (2018) have estimated that ambitious climate policies would lead to a net increase of jobs in various jurisdictions, with the number of lost jobs in fossil fuels more than made up for by jobs in renewables and energy efficiency.

In the broader context beyond the United States, the International Renewable Energy Agency estimates in a 2020 report that ambitious climate policies will lead to more energy jobs across North America. Under its “Transforming Energy Scenario,” which aligns with the long-term climate targets of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the total number of energy jobs in 2050 will be 1.9 million greater than in a “Planned Energy Scenario,” under which governments implement current and announced policies.

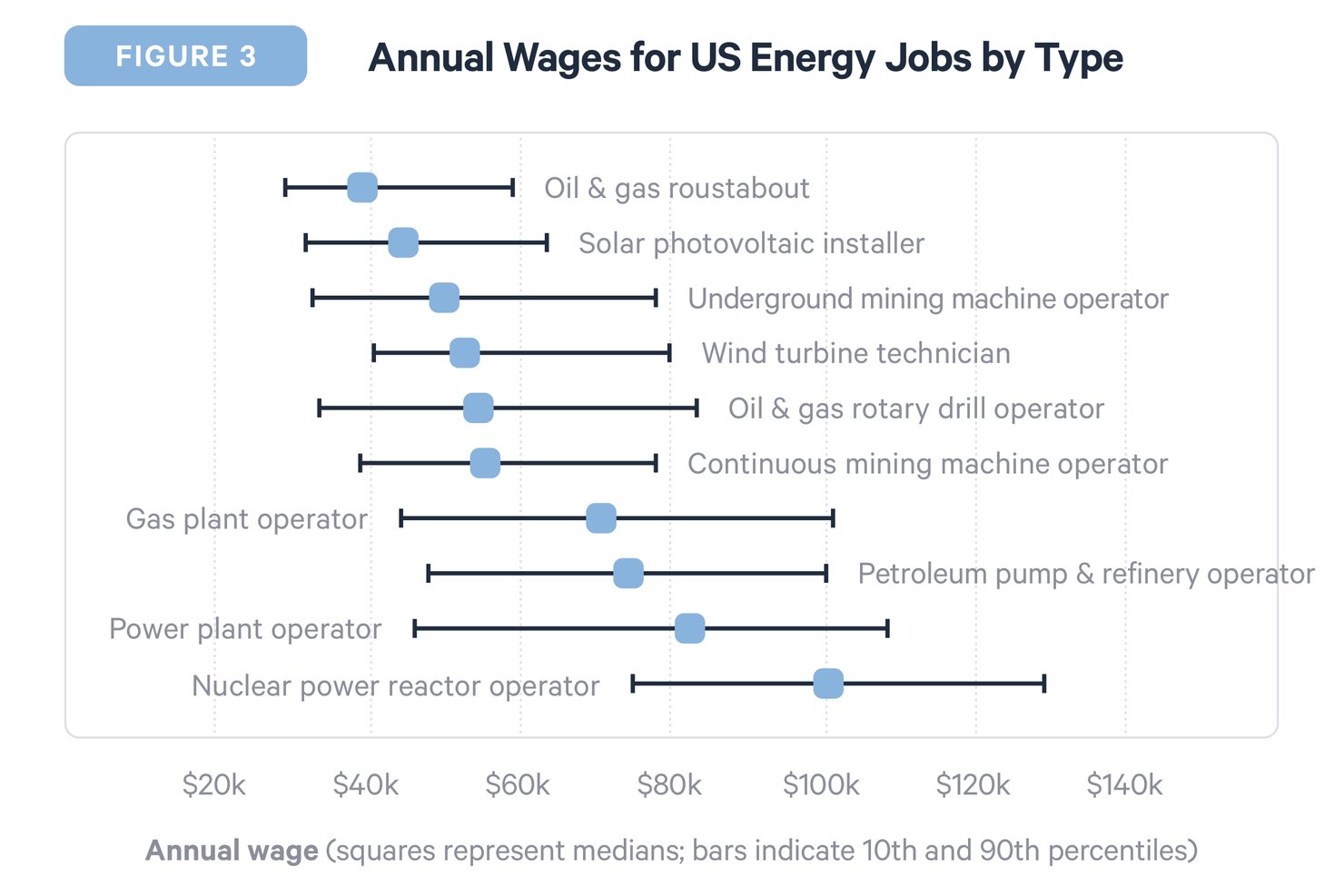

While these projections may offer encouraging news, the number of jobs is just one of many considerations. For example, a 2020 analysis by North America’s Building Trades Unions using focus groups and surveys found that tradespeople in the United States perceive fossil energy jobs as providing better wages and benefits than renewables such as wind and solar.

Another relevant metric for assessing job quality is union density. Across the United States, overall union density averages about 6 percent, according to a 2020 report about energy and employment by the National Association of State Energy Officials and Energy Futures Initiative. In solar and wind, the rate is 4 and 6 percent respectively; but for workers in power plants fueled by coal, natural gas, and nuclear, the rate is 10 to 12 percent.

Unionization, along with education, training requirements, and other factors, all shape energy wages. Domestic wage data on energy jobs offer a nuanced picture: some fossil energy jobs, such as oil and gas rig employment or mining machine operation, offer similar wages as jobs related to the installation and service of wind and solar equipment. However, those who operate oil and gas processing facilities or thermal power plants (particularly nuclear plants) earn considerably more.

A crucial question for policymakers in the years ahead will be: At what expense should we prioritize job creation in energy and environmental policies? For example, education policy focuses on achieving better student outcomes, while diplomacy seeks to advance US geopolitical interests. Although rhetoric around energy and environmental policy has focused on job creation (or destruction), policymakers will also need to focus on cost-effectiveness and the equity outcomes that result from their decisions.

Equity and Efficiency

Scholarly research has paid relatively little attention to the employment implications of different energy policy choices. But plenty of research has covered the cost-effectiveness and distributional implications of energy policies, and here, the lessons are more straightforward.

A plethora of work has demonstrated that broad-based policies targeting entire sectors (e.g., performance standards in the electricity sector) or the wider economy (e.g., economy-wide carbon pricing) will tend to reduce emissions at lower cost than the types of technology-specific policies more often enacted by the federal government and many US states. What’s more, some of these policies, such as subsidies for rooftop solar, electric vehicle purchases, and certain energy efficiency programs, have tended to disproportionately benefit high earners, as noted by Borenstein and Davis (2016) and Fournier and other researchers (2020).

Despite these consistent findings, technology-specific subsidies and standards continue to spread across the United States. Why? One reason is jobs.

From a political perspective, policymakers can easily point to technology-specific subsidies such as wind, solar, or energy efficiency and connect those policies with job growth in the relevant fields. For technology-neutral policies such as carbon pricing, the rhetorical link is less clear. In addition, the well-known political challenges of enacting a carbon price, along with persistent skepticism about the role of markets in reducing pollution, contribute to the growth of technology-specific policies.

In Transition

So, is it feasible to serve three masters? Can policies thread the needle to support an energy transition while also providing jobs, enhancing equity, and achieving cost-effectiveness?

We don’t have all the answers yet, but recent experience suggests that fully satisfying all three criteria will be a challenge.

In some cases, such as in California and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (not to mention most of Europe), policymakers have deployed a mix of carbon pricing and other policies, including renewables mandates and energy efficiency programs. Although this mixed-policy approach reduces the carbon price and the cost-effectiveness of the policy overall, it may offer a more politically viable path forward for policymakers who would prefer to focus their messaging on job creation rather than carbon taxation. But keeping a carbon price in the mix remains crucial, as carbon pricing raises revenue that can support those who are displaced from jobs in fossil energy and those who suffer from a legacy of environmental injustice.

A new series of reports I’m writing with Resources for the Future colleagues Wesley Look and Molly Robertson, along with Jake Higdon of the Environmental Defense Fund, lays out some options for federal interventions that focuses on supporting workers and communities that currently depend on the fossil fuel industry, with the first report focused on economic development policies. Our work in this area is in its early stages, and future reports will cover workforce development, the social “safety net,” environmental remediation, and other policies that may play a meaningful role in what is often referred to as a “just transition.” Additional work will describe in detail the cost-effectiveness and energy justice impacts of different clean-energy deployment policies.

Not Just a Transition

The economic effects of a transition to clean energy will be consequential for households across the United States and the world. Such a transition not only will prevent the worst impacts of climate change—it will also create new opportunities for entrepreneurs and workers in clean energy across the economy. But considerable uncertainties remain, particularly for people in fossil energy regions who worry about the backbone of their local economies, and for those who struggle to afford heating in winter and cooling in the summer.

Identifying an equitable path forward is more than a moral imperative; it can smooth the path to a politically viable climate policy for an issue that has become increasingly polarized. But we will need to be clear-eyed about the challenges, including the need to balance the competing priorities of jobs, equity, and efficiency.