Coal-fired power generation in the United States has been in a decade-long decline, a trend repeatedly punctuated by plant closures (from Montana and Colorado to Indiana and Massachusetts) and mine bankruptcies (notably including Arch Coal, Peabody, Cloud Peak, and Blackjewel). The Trump administration has floated several policies to save the dying industry. Proposed profit guarantees for coal and nuclear plants, mandates to buy coal and nuclear power, and the establishment of a “Strategic Electric Generation Reserve” were widely covered and well-known policy proposals, and readers of Resources magazine may already be aware of them. But even many well-informed observers of the US power sector have never heard of another billion-dollar federal subsidy for burning coal—specifically, the federal tax credit for so-called “refined coal,” a chemically processed kind of coal supposed to produce less air pollution than regular coal. The “refining” process involves spraying a mixture of chemicals on the coal, a technique meant to reduce emissions produced when it is burned—in particular, emissions of nitrogen oxide (NOₓ), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), and mercury.

However, this subsidy is failing to achieve its goals, and the emissions reductions achieved in practice are much smaller than the tax law requires. The policy—a $7/ton tax credit for refined coal use—is currently set to expire in 2021, but several new bills have been introduced in recent months on Capitol Hill to extend the credit (e.g., S. 1327 and S. 1405). These updates provide a great opportunity to reevaluate—and reconsider—the refined coal subsidy.

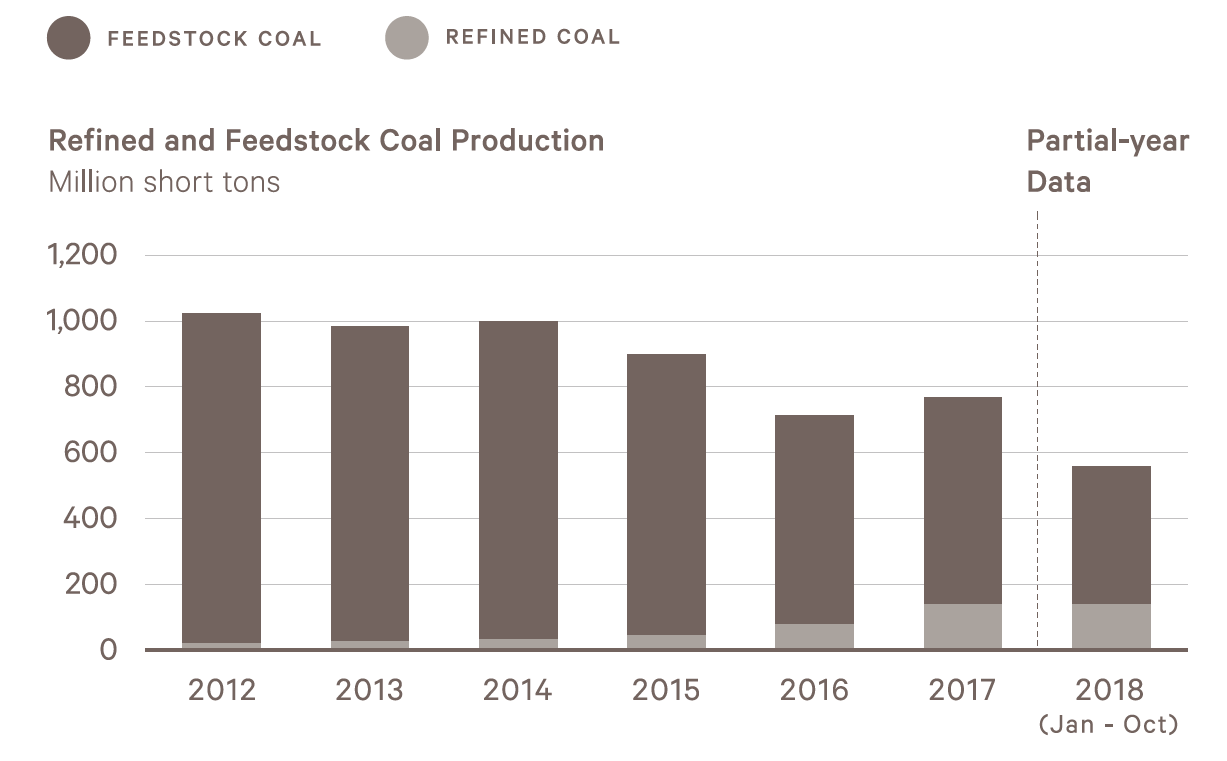

Refined coal comprises more than 20 percent of coal used in the US power sector, and that number is growing as more plants bring refining operations online to take advantage of the tax credit (Figure 1). The $7/ton tax credit represents a large fraction of the market price of coal (10–15 percent of the price of bituminous coal from the eastern United States and 35 percent of the price of lignite, another type of coal). Given that more than 120 million tons of this stuff is burned every year, the tax credit amounts to nearly $1 billion annually in subsidies for burning coal, something most economists argue should be taxed, due to the associated unintended consequences (i.e., negative externalities), rather than subsidized.

Figure 1. Coal Consumption over Time

(Source: US Energy Information Administration. 2019. Today in Energy. February 8. Washington, DC: US EIA)

This tax credit can generate a lot of revenue for a struggling coal plant with thin margins. A typical coal plant that burns, say, three million tons of coal each year would generate $21 million annually in tax credits. This can account for a nontrivial fraction of a plant’s fuel costs, which would amount to about $120 million per year for our hypothetical plant (based on an average coal price of $40 per ton for three million tons). This simple comparison undersells the relative value of the tax credit because it is a post-tax value, and the pre-tax equivalent would be 30 percent to 50 percent higher. In addition, much of this substantial windfall often accrues to outside tax equity investors (often including major financial services and pharmaceutical companies), rather than being fully passed on to the coal plants themselves or to energy consumers.

So why are the tax credits in place? The stated purpose of these credits is to reduce harmful emissions from coal plants. That sounds great—but there are reasons for concern.

First, some background. The refining process involves spraying regular coal with a set of chemicals to reduce the amount of air pollution created when that coal is burned. The tax code sets specific requirements for companies to be eligible to receive the credits: burning the refined coal must produce 20 percent less NOₓ and 40 percent less SO₂ or mercury, relative to burning the same amount of unrefined coal.

Less pollution sounds great, but are we getting those 20 percent and 40 percent reductions in practice? This is where things go a bit off the rails.

The IRS lets companies demonstrate compliance with these targets through laboratory tests that are run under a fixed set of conditions; however, operating conditions in the lab can easily diverge from conditions in the field. (The IRS lets companies demonstrate compliance in the field, but apparently most companies opt for the lab tests, which rarely fail. One lab in North Dakota reportedly runs the tests for many plants across the country.)

In a recent study I conducted with RFF colleague Alan Krupnick, we consider how emissions fared in the field (as opposed to in the lab) at plants burning refined coal. The recent rise in the number of plants burning refined coal allows us to examine emissions immediately before and after the switch, as shown for a typical coal plant in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Fuel Consumption and Emission Rates at an Illustrative Plant

This plant is located in the Midwest, and its fuel use and emissions data comes from publicly available sources at the Energy Information Administration (EIA) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). After switching from regular coal to refined coal in November 2016, this plant showed no obvious reductions in emissions rates for NOₓ (top right), SO₂ (bottom left), or mercury (Hg, bottom right). The plant did not install or dismantle pollution control equipment or change coal suppliers during this period, so we should be able to observe the emissions impacts—if any—of refined (versus unrefined) coal.

But the plant doesn’t appear to be reducing emissions at all—nor does it come even close to the emissions reductions required to receive the tax credit. Nonetheless, the plant can claim the credit, so long as the lab tests pass. This disconnect is neither economically efficient nor a cost- effective use of taxpayer dollars.

Broadening our scope from the data of a single power plant to a dataset covering virtually all coal-fired power plants in the United States, we can get a comprehensive take on the emissions impacts of refined coal. The result: There are, on average, some reductions in NOₓ and mercury emissions; however, they fall well short of the 20 percent and 40 percent targets prescribed by the tax law. The actual reductions miss the targets for NOₓ and mercury by about half, with no reductions at all in SO₂.

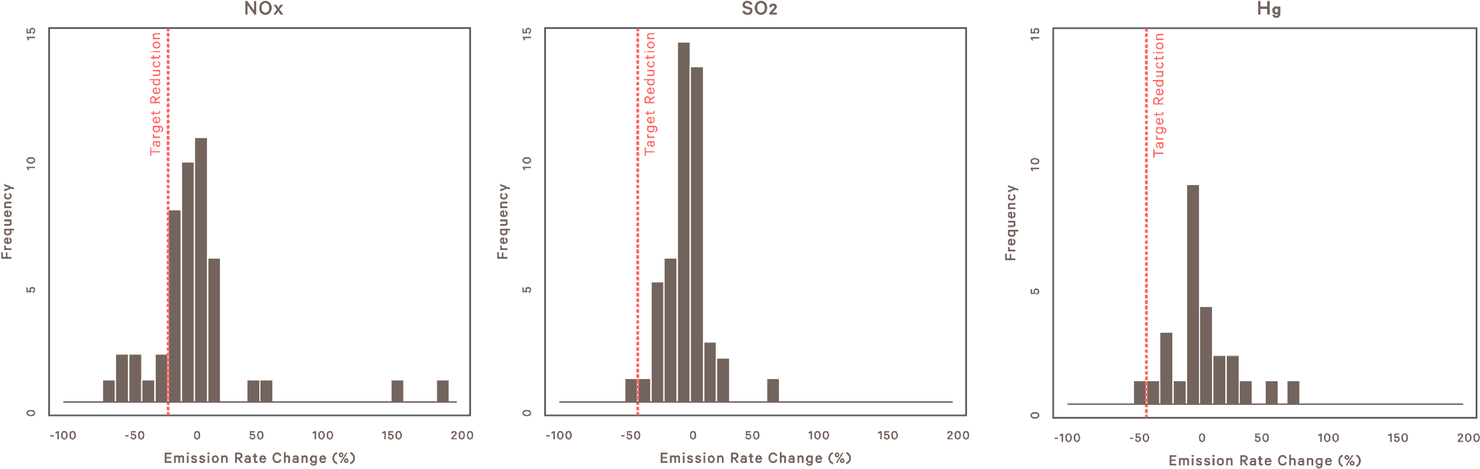

These numbers are averages, but we also can calculate reductions at the more granular level of the individual boiler. (Power plants often have multiple boilers.) Getting this granular with the data, we can’t find any individual power plant that achieves the legal targets. Figure 3 shows histograms of the boiler-level estimated emissions reductions. Only two boilers are estimated to achieve the 40 percent reduction target (one for SO₂ and one for mercury), but neither of those boilers achieve in tandem the required 20 percent NOₓ reduction.

The policy is failing to achieve its goals, and companies are claiming the generous tax credit without actually reducing emissions in the field.

Figure 3. Histograms of Boiler-Level Estimated Emission Rate Reductions

Perhaps the 20 percent and 40 percent targets were too ambitious. A failure to achieve ambitious targets doesn’t necessarily mean that the policy is actively making things worse. It’s conceptually possible that the underwhelming benefits we estimate, while smaller than hoped, still justify the costs. We explored this possibility by calculating the extent to which burning refined coal can benefit human health.

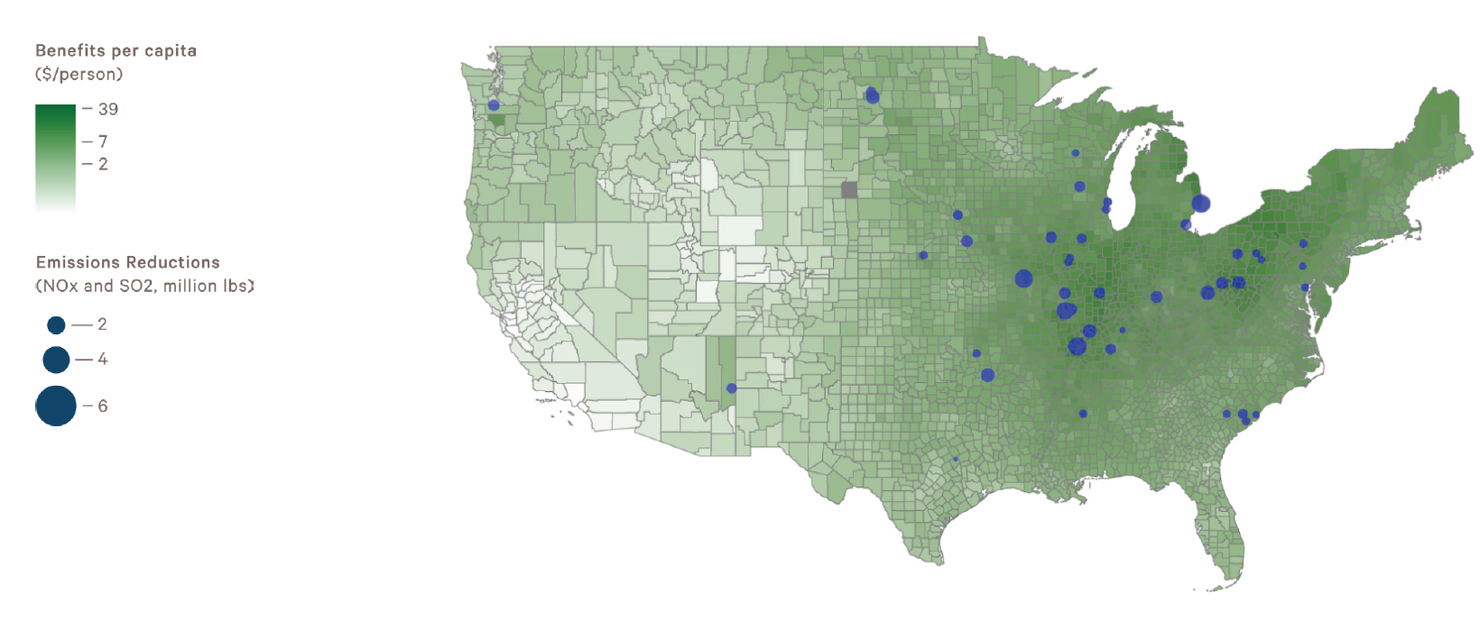

Reductions in those pollutants, particularly NOₓ and SO₂, improve air quality through reduced formation of particulate matter in the atmosphere. Those particulates are linked to premature mortality, so reductions in NOₓ and SO₂ emissions benefit people’s health. We quantify these benefits by calculating the reduction in premature mortality from the emissions reductions we observe. We then convert those reductions in mortality into a monetized value based on the widely used value of a statistical life. In the end, we estimate benefits on the order of $460–590 million annually, or about $4–5 per ton of refined coal—which falls well short of the subsidy costs of about $7 per ton. (For the economists in the audience, the taxpayer cost and the social cost—in other words, the refining cost plus the excess burden of taxation—both coincidentally come out to about $7/ton.)

Figure 4. Distribution of Air Quality Benefits (Dollars per Capita, 2017$) from SO₂ and NOₓ

But even the estimated benefit of $4–5 per ton is probably an overstatement. For one thing, many coal plants are covered under cap-and-trade policies for NOₓ and SO₂, so any emissions reduction at one plant simply frees up permits that allow other plants to emit more, and we haven’t accounted for this so-called “waterbed effect.” Second, we have assumed that the subsidy doesn’t affect the amount of coal burned. But when you subsidize something, you get more of it. In reality, the subsidy has likely increased coal consumption by increasing plants’ dispatch and delaying their retirements, which would increase emissions. Third, we haven’t accounted for the negative water quality impacts of the coal refining process, which can leak bromides into drinking water supplies and create carcinogens.

In summary, even though we likely are overestimating its benefits, the subsidy still fails to justify its own cost.

That said, the policy could hypothetically pass a cost- benefit analysis if refined coal could achieve the 20 percent reduction in NOₓ and the 40 percent reduction in SO₂; however, industry engineers are skeptical that the refined coal can actually reduce SO₂ by the required 40 percent. This technological limitation explains why most refiners aim to comply by targeting mercury, and not SO₂, for the 40 percent reductions. Indeed, the engineering literature reveals much more experience with refined coal reducing mercury emissions at coal plants. If we assume plants comply by reducing mercury emissions instead of SO₂, we find that the policy fails a cost-benefit analysis even if the 20 percent and 40 percent targets are met. This is because the quantifiable benefits of mercury reductions are very small. For example, EPA’s regulatory impact analysis of the Mercury and Air Toxics Rule estimated benefits of only $4–6 million in present value for much larger reductions than we estimate. With negligible mercury benefits, the 20 percent NOₓ reductions are not enough on their own to justify the policy’s costs.

So where does that leave us? The policy doesn’t appear to be working as intended, since emissions reductions demonstrated in the lab don’t arise in the field. The modest improvements to air quality don’t appear to justify the policy’s costs. More generally, otherwise uneconomical plants may be kept around, supported by taxpayer funds, with little to no environmental benefits to show for it, and with additional risks to drinking water.

Fortunately, several senators on Capitol Hill have taken notice of this work and begun asking questions, including questioning the IRS’s enforcement procedures.

Ultimately, the decision of whether or not to extend this billion-dollar subsidy has critical impacts on industry, taxpayers, air quality, and human health.