A case study for estimating the effects of climate change.

Climate change is affecting our world today, and these effects will become more significant in the years to come. In the United States, one state that is particularly susceptible to some of the most damaging consequences of climate change is Florida.

Florida’s long coastline and low-lying land make it particularly vulnerable to the damaging impacts of rising sea levels, which are projected to rise faster in Florida than the global average. Florida is also more exposed than any other US state to damages from tropical storms. Because the average age in Florida is higher than in most other states (with a larger share of the population older than 65), some communities in Florida are at higher risk due to rising temperatures.

The discussion that follows, punctuated in the next several pages by illustrations, provides an overview of the implications of a changing climate for Florida and the people who live there, mostly drawn from projections over a 20-year horizon. We examine climate change projections in Florida under two plausible scenarios: a moderate-emissions scenario, where global greenhouse gas emissions rise by roughly 1 percent annually over the next 20 years; and a high-emissions scenario, where emissions rise by 3 percent annually. These scenarios are drawn from an extensive literature and correspond with climate scenarios known as Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 4.5 and 8.5. We apply similar scenarios for future sea level rise.

These projections include substantial uncertainty ranges for two key reasons. First, the future level of greenhouse gas emissions is unknown. Generally speaking, lower levels of emissions lead to lower damages. Second, despite major advances in climate science over the past several decades, there is still large uncertainty surrounding the Earth’s response to a given level of emissions. For example, the IPCC in its most recent Assessment Report estimates that the long-term warming associated with a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide levels spans a “likely” (66% probability) range of between 3°F and 8°F.

Results are based on our review of the available literature, and relies in several cases on the work of the Climate Impact Lab, an interdisciplinary group producing detailed local projections of the effects of climate change.

High resolution infographics: https://media.rff.org/documents/FCO_Infographics_rREdvLr.pdf

Sea Level Rise

Climate change raises sea levels by increasing ocean temperatures (which causes water to expand) and by melting glaciers and ice sheets (which adds water to the oceans). Before land is permanently submerged, rising seas will lead to higher and more frequent coastal flooding. Several major tourist attractions, including the Everglades, Biscayne National Park, and Miami Beach, are largely situated on land less than three feet above the high-water mark and may become permanently submerged by the end of the century. Higher sea levels can also raise the groundwater level, indirectly increasing the severity of flooding by decreasing the capacity of the soil to help with drainage, which results in floodwaters remaining higher for longer periods of time. Extreme flooding that previously would have been expected to occur just once every 100 years (a “100-year” flood), with waters reaching 2–3 feet above the high-water mark, will become more frequent.

As sea levels rise, ocean water will continue to move farther inland into freshwater aquifers in a process known as saltwater intrusion, posing a contamination threat to drinking water and agriculture. Particularly at risk is the Biscayne aquifer, located under Miami-Dade County, which provides drinking water to around 4.5 million people.

High resolution infographics: https://media.rff.org/documents/FCO_Infographics_rREdvLr.pdf

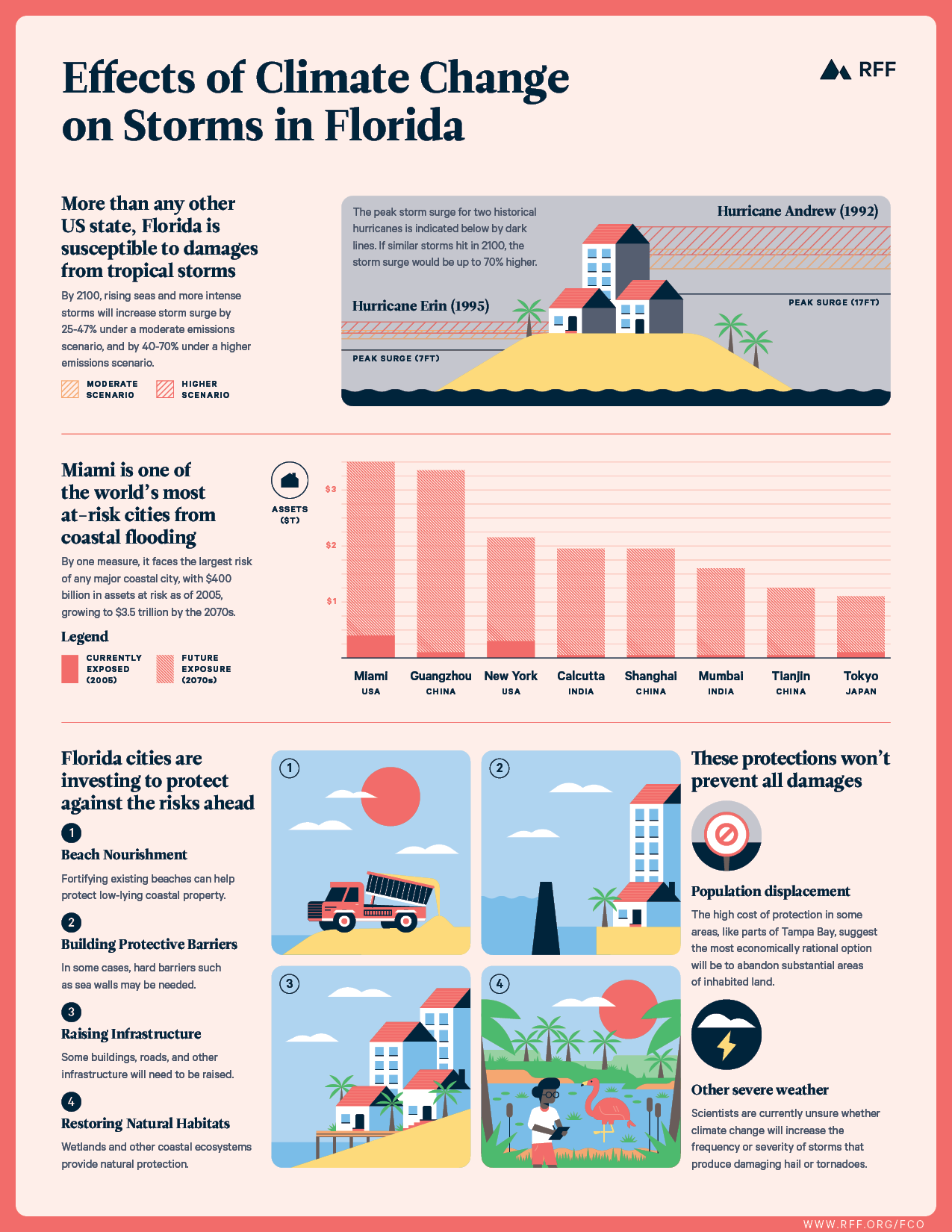

Storms

More than any other US state, Florida is susceptible to damages from tropical storms, and climate change is projected to increase these risks. The most severe property damage from tropical storms is typically caused by storm surges. Although many communities have prepared for a certain level of surge, small increases above that preplanned level can lead to a large increase in damages and even disruption of evacuation routes. More severe storms not only pose risks to human lives and prosperity—they also reduce regional economic output over the short and long term. While a variety of protective measures can reduce damages, existing research suggests that the most economically rational option in some cases will be to abandon substantial areas of currently inhabited land, by the end of the century.

High resolution infographics: https://media.rff.org/documents/FCO_Infographics_rREdvLr.pdf

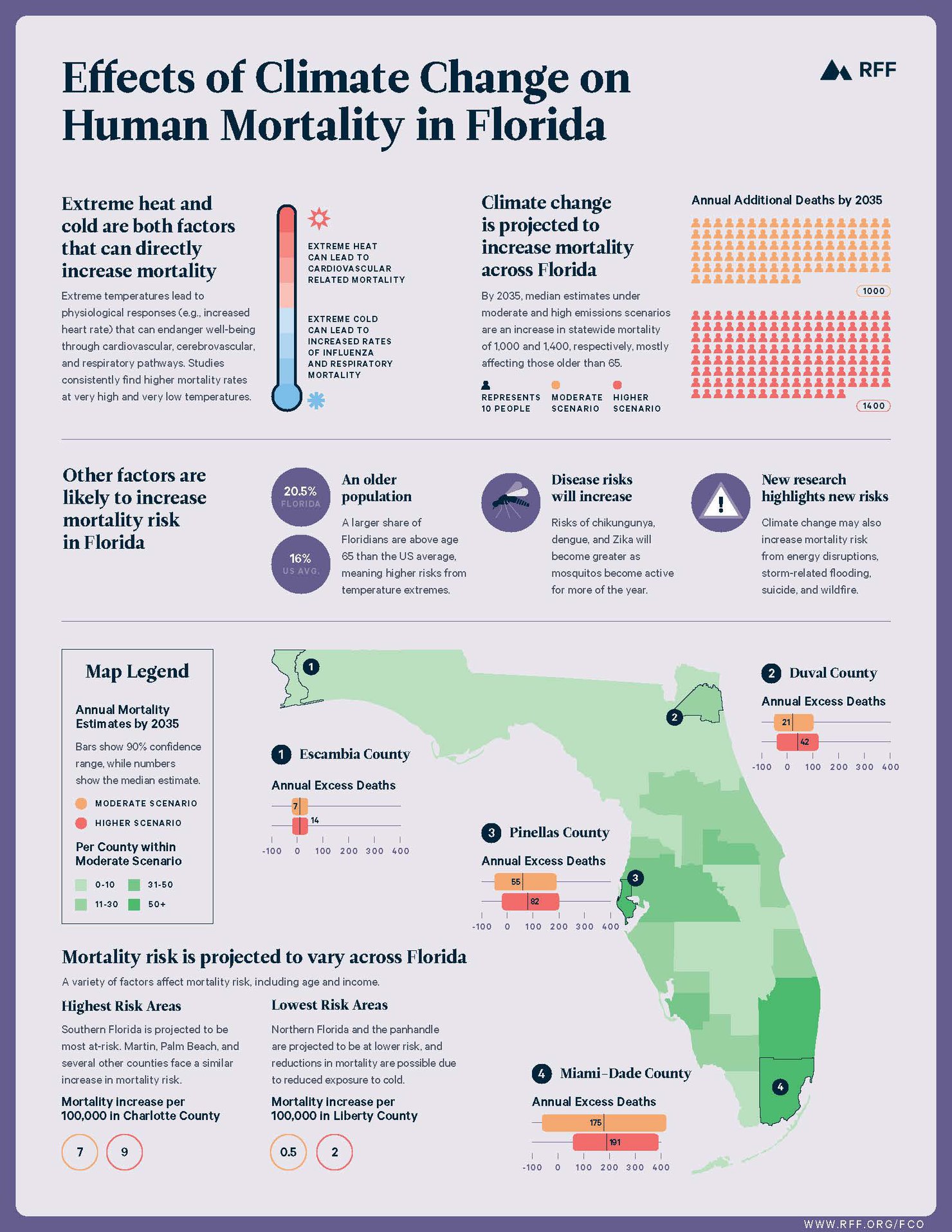

Human Mortality

Climate change directly affects mortality rates through physiological responses to heat or cold. Climate change also is likely to indirectly affect human health through changing patterns of disease vectors (i.e., mosquitoes and other organisms that can transmit diseases), extreme weather, human conflict, and other environmental or socioeconomic pathways. Other risks that increase due to climate change result from energy supply disruptions, storm-related flooding, suicide, and wildfire.

High resolution infographics: https://media.rff.org/documents/FCO_Infographics_rREdvLr.pdf

Climate Policy

Momentum is growing in the US Congress to address climate change, and many legislators are turning to carbon pricing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly and efficiently. These carbon pricing policies charge emitters for the carbon dioxide (CO2) they release into the atmosphere through the combustion of fossil fuels. Our analysis uses two models of the US economy, built by RFF researchers to estimate the effects of these proposed policies on US and Florida households. Importantly, the models do not account for the benefits of avoiding climate change or the benefits of investments in infrastructure and green technologies. (Explore the impacts in greater depth using RFF’s interactive Carbon Pricing Calculator tool.)

Of the eight policy proposals we analyze, initial carbon prices range from $15 to $52 per ton of CO2, rising at different rates over time. The most important policy design choice that determines how households are affected is how the revenues from carbon pricing are used. We find that climate policies can reduce household income; however, carbon pricing also generates substantial revenues that can significantly benefit households by, for example, distributing dividends (lump-sum payments to households) or reducing taxes. Most existing proposals that distribute dividends leave low-income households better off, while high-income households are made worse off.

High resolution infographics: https://media.rff.org/documents/FCO_Infographics_rREdvLr.pdf

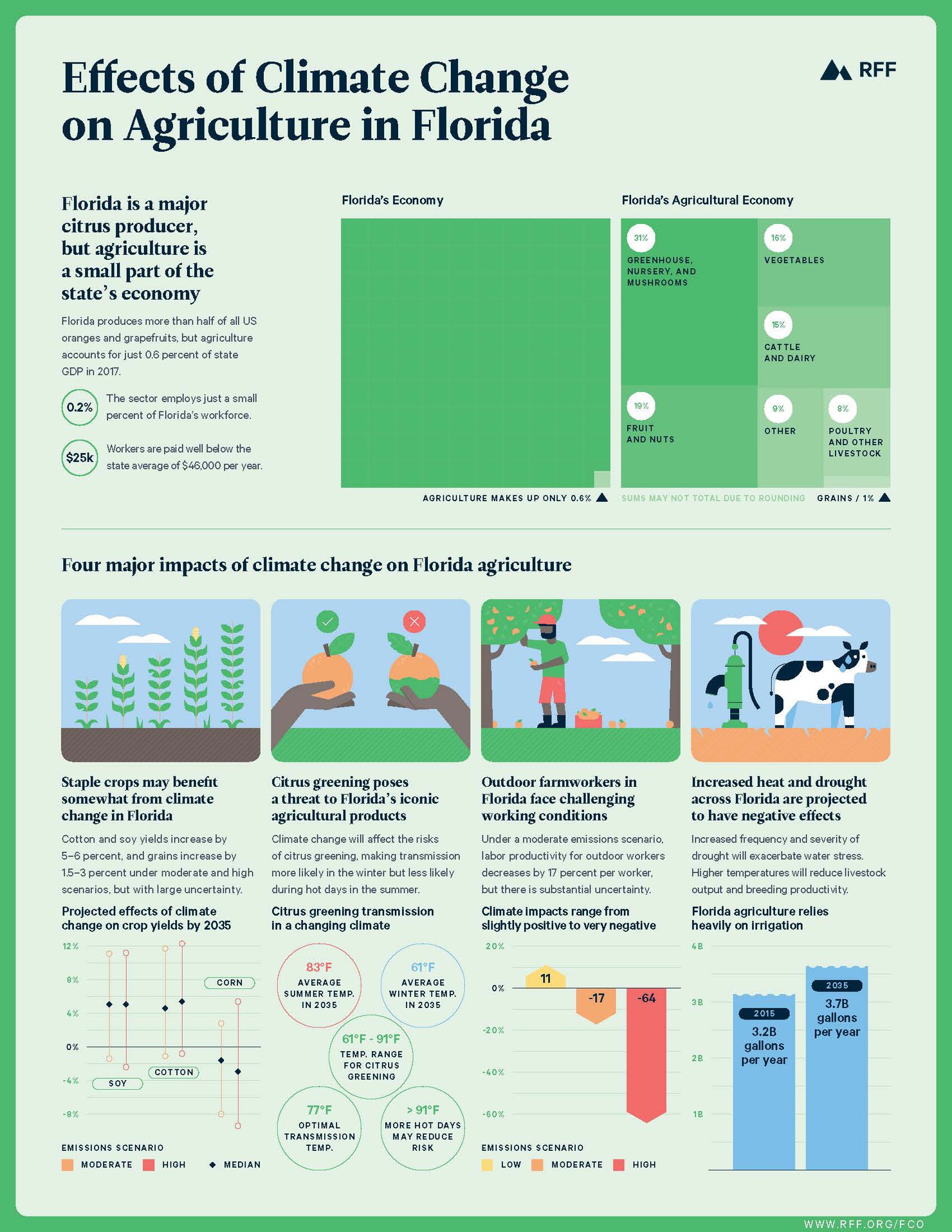

Agriculture

The relatively small role of agriculture in Florida’s economy suggests that any impacts are unlikely to have major economic consequences for the state as a whole. However, climate change is projected to increase the frequency and severity of droughts in Florida, which would exacerbate competition for Florida’s water resources. In 2015, the state’s farms consumed 3.2 billion gallons of fresh water per day—and this figure is projected to rise by 17 percent through 2035. In 2017, roughly 75 percent of Florida’s planted cropland was irrigated mechanically (i.e., not rain-fed). As droughts intensify, crop irrigation may become more costly.

Warmer temperatures are projected to have a variety of other negative effects, including reduced labor productivity for outdoor farmworkers and reduced productivity of livestock and dairy cows.

Read and download the full report here. Find high resolution infographics here.

The authors acknowledge the VoLo Foundation for funding this project.