Consumers may not have given much thought to who supplies their electricity, or how, but they should know that a tremendous battle is being waged behind their electrical sockets. Just as several long-distance telecommunication carriers (AT&T, Sprint, MCI) now compete to serve each household, so too firms with currently unfamiliar names may one day—in the not-so-distant future—be competing to supply household electricity. Whether, when, and how this happens are questions at the center of a vigorous debate occurring in Washington, in state capitals, and in courtrooms around the United States.

California proposal to open the electricity market

Traditionally, households and businesses have had little choice when it comes to buying electricity. Utility companies providing electricity were granted exclusive service areas (or monopoly franchises) by the states in which they operated. In return, electric companies were obligated to provide service to all customers within that territory who wanted it. And the rates electric companies could charge for the electricity they sold were regulated by state public service or public utilities commissions.

Earlier this year in California, however, the public utilities commission floated a proposal that sent tremors throughout the electricity industry, not only in California but everywhere else as well. Under this proposal, by 1997 large industrial customers in California—a factory, for example—could buy power from any supplier, including electricity brokers or nonutility generators. Individual homeowners would have a similar option by 2002; in other words, they could shop around for electricity "bargains" in the same way they shop for other commodities. The local utilities, for whom these customers used to be captive, would be required to wheel the power—that is, the local utility would have to use its power lines to bring to each factory or home the bargain electricity that customer had purchased elsewhere. In return for this service, the local utility would be paid a fee.

Thus, under the California proposal, if a power producer in Nevada could generate more electricity than it could sell to its customers there, it could sell the surplus power to customers in California if its price were attractive compared to the price charged by California electric utility companies. To say the least, such an arrangement would represent a fundamental shift in the way electricity service is provided. Michigan, Wisconsin, Texas, and several other states are either experimenting with or contemplating similar changes, though none have gone so far as California.

Under the California proposal, by 1997 large industrial customers in the state could buy power from any supplier, including electricity brokers or nonutility generators.

The debate sparked by the California proposal—whether consumers should have the right to purchase power from sources other than their local utilities—can be traced back to the Energy Policy Act. Little noticed when it was signed into law by then-President George Bush in October 1992, the Energy Policy Act gave the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission expanded authority to order utilities to use their transmission and distribution lines to make available electric power generated by other utilities and nonutilities. That authority applies only to wholesale transactions—that is, sales of electricity from one utility company to another. But the competitive forces unleashed by the Energy Policy Act have prompted interest in extending this competition to all levels of the industry and to all consumers of electricity.

Two sides of the restructuring debate

There are many reasons for the recent interest in enhanced competition in the electricity business. One is the wide disparity in prices paid by electricity consumers, not only in different regions of the country but even within a single state. For example, the Pennsylvania cities of Pittsburgh and Uniontown are only fifty miles apart, but homeowners in Pittsburgh pay 12.4¢ per kilowatt hour for their electricity, while Uniontown homeowners pay only about half that, 6.5¢ per kilowatt hour. Similar disparities in rates exist among states and regions of the United States and between industrial and commercial users. These disparities can create very real competitive consequences when a firm in a higher-cost area competes against one in a lower-cost area.

Proponents of the "shopping" approach to electricity argue that consumers will benefit if given the opportunity to hunt for the lowest-priced electricity. They argue that only through competition will inefficiencies associated with the current structure and regulation of the electric utility industry be eliminated. As evidence, they point to the substantial reductions in long-distance telephone rates in the wake of deregulation in that industry.

Many utilities, small consumer groups, and environmentalists argue that moving to wide-open competition in electricity markets will benefit only the largest industrial customers.

Countering these arguments for "shopping," however, are many utilities, small consumer groups, and environmentalists, who argue that moving to wide-open competition in electricity markets will benefit only the largest industrial customers. Rather than producing lower rates for all consumers, these opponents argue that extending supplier choice to the retail level will only result in costs being shifted from large customers, who are most attractive to new suppliers, to smaller customers. Moreover, environmentalists and consumer advocates worry that making electricity markets more competitive could jeopardize many programs currently conducted by utilities to protect low-income households, conserve energy, and develop new, more environmentally benign electricity-generating technologies. In 1992, for example, electric utilities spent $2.2 billion on energy conservation programs (called demand side management, or DSM), up from $1.7 billion the previous year.

Industrial customers have long argued that DSM, low-income assistance, and other programs increase their electricity rates while the benefits of such programs have accrued mostly to other customers. If these industrial customers were free to shop around for electricity, they would seek to avoid paying for such programs. (In much the same way, after years of subsidizing local telephone service, businesses took advantage of cheaper long-distance telephone rates when they became available). Thus, if DSM and other socially desirable programs carried out by utilities—acting essentially as agents of the government—are to continue in a more competitive electric utility industry, these programs will have to be funded through different mechanisms. Faced with competition from nonutility electricity generators who do not undertake similar programs, utilities already are reducing DSM spending and cutting back on research and development efforts.

The advent of nonutility generators and new technology

The debate over competition in the electricity industry is fueled further by the growing share of electricity that is being supplied by entities other than traditional utility companies. These nonutility generators include companies that produce electricity as a byproduct of, say, steel or chemical production (called cogenerators); small producers using unconventional fuels, such as biomass or geothermal energy; and independent power producers, which produce electricity using traditional fuels but which do not own distribution or transmission facilities. Such nonutility power producers own electric-generating capacity but, unlike traditionally regulated electric utilities, they lack a designated service area.

Since 1978, when the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) was passed to encourage the construction of cogeneration and small power plants using unconventional fuels, these nonutility producers have supplied an increasing amount of U.S. electricity. Although still responsible for less than 10 percent of the electricity generated nationwide, each year since 1991 they have brought more new generation capacity into service than have utilities. Moreover, in certain states (such as California, Virginia, and New Jersey), nonutility generation has grown to account for more than 20 percent of the state's installed generation capacity. Using new technologies, such as highly efficient, combined-cycle, natural gas turbines, and taking advantage of historically low natural gas prices, nonutility producers frequently generate electricity at a cost below average utility system costs.

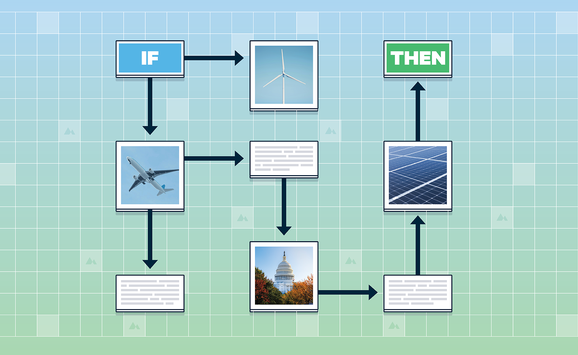

This is not the first time in the history of the electric industry that new technology has offered cost advantages. What is new, however, is the argument that the benefits of new technology should be available directly to certain customers, rather than to all customers through the utility as their supplier. The key issue, then, is whether new, advantageously priced electric supplies should continue to be sold to utilities as "portfolio managers" for all customers or whether some or all individual customers should be able to purchase power directly from the supplier of their choice, thereby obtaining for themselves the benefit of new technology.

An obligation to serve

A serious complication in the debate about enhanced competition in the electricity industry has to do with the electric utilities' historic obligation to serve. If customers are allowed to choose suppliers other than their local utility, must the utility be prepared to resume service if, after leaving the grid to shop around, a customer wishes to return? Fairness would seem to dictate that allowing customers the right to shop around for power should free the utility of any obligation to serve them in the future. Customers (and society), however, may not be prepared to assume the risk that some customers could become, quite literally, "powerless."

Historically, the obligation of utilities to serve all customers has had a flip side that benefited utility companies. Generally speaking, once state utility regulators had given companies approval to construct new plants, the utilities were permitted to recover the costs of those plants through the rates they charged. Plants that, in hindsight, were not such good ideas nevertheless were paid for by consumers, along with the plants that turned out to be bargains and were worth more in the market than regulated rates reflected.

What will happen in a more competitive environment if utilities cannot pass along to electricity consumers the costs associated with high-cost plants and other commitments undertaken voluntarily or by direction from regulators to meet customer needs? Will stockholders be forced to "eat" the costs associated with these stranded assets? Should the low-cost generators, or the customers for whom these costs were incurred and who will benefit from competition, be required to bear some of these costs? These questions raise critical issues that have yet to be resolved.

With enhanced competition, what becomes of the electric utilities' historic obligation to serve? Customers and society may not be prepared to assume the risk that some customers could become, quite literally, "powerless."

The industry of the future

The stakes associated with this battle over the future role of competition in the electricity industry are substantial. Some $200 billion worth of electricity is sold each year in the United States, making the electric utility industry not too much smaller than the auto industry. Some $500 billion has been invested in electric plants and equipment. And more than $25 billion is being spent each year to upgrade and replace this capital stock.

Depending on how the transition to greater competition in the electricity industry is structured, electricity consumers, generators, shareholders, and the financial community all fear the possibility of large losses. Utilities with high rates relative to the marginal cost for production for the region within which they operate (for example, those utilities required to purchase large amounts of high-cost power under PURPA, and some with recently completed nuclear power plants) are especially at risk of financial loss.

The rough outlines of the electric utility industry of the future are beginning to emerge. Almost certainly, there will be disaggregation of the vertically integrated utilities we have known in the past. Generation, transmission, and distribution are likely to be separate functions, if not separate companies. Some experts and participants in the debate favor a system in which atomistic buyers and sellers negotiate bilateral contracts. Others favor a system in which all electricity transfers are coordinated by a central controller. This controller would run an organized spot market for electricity and dispatch power based on the bids of buyers and sellers. Some argue that there is a role for both a central spot market and bilateral contracts.

Regardless of the system that results, the electricity industry of the future will differ as much, or more, from the industry of fifteen years ago as modem financial institutions or telecommunications companies differ from their seemingly prehistoric ancestors. As our economy becomes increasingly electrified—demand for electricity continues to grow faster than that for other energy sources and faster than growth in gross domestic product—the change is one we would all do well to watch closely.

Linda G. Stuntz is a partner in Van Ness Feldman, P.C., a law firm located in Washington, DC, and a member of RFF'S board of directors. She thanks Cheryl Feck of Van Ness Feldman for helping to develop this article.

A version of this article appeared in print in the January 1995 issue of Resources magazine.