Stanford University Professor and Resources for the Future (RFF) University Fellow Jon A. Krosnick has collaborated with RFF since 1997 to explore American public opinion on issues related to climate change. This year’s report is the first in a new series by researchers at Stanford University, RFF, and survey research company ReconMR. The survey results show that opinions on climate change have become increasingly entrenched, and the group of people who care deeply about climate change has grown—all in spite of a pandemic that otherwise could have diverted attention and diminished support for climate change mitigation.

Is concern about the natural environment a “luxury good,” subject to fluctuations based on attention to other crises that take priority and have increased relevance in the moment? According to one theoretical perspective, people can afford to worry about protecting the planet’s natural environment only if their basic survival needs have been satisfied. A plausible foundation for such an argument is Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs.”

Maslow posited that people are motivated by the desire to satisfy various types of needs, which have been represented most often by a pyramid (Figure 1). Maslow called the lower levels of the pyramid “deficiency needs”—the basic requirements for survival that must be satisfied, including having enough food, a place to sleep, and physical safety.

According to Maslow, until those basic needs are satisfied, an individual will focus on eliminating those deficiencies. Once those needs have been met, people have the opportunity to pursue psychic contentment in the form of friendships, intimate relations with others, and feelings of self-esteem and worthwhile accomplishment.

Only after the four lower tiers of needs have been met does an individual enjoy the luxury of worrying about the greater good of societies, says Maslow. And perhaps concern over the environmental health of the planet, in the present and in the future, is a possible subject of a person’s attention only if all deficiency needs have first been satisfied.

The novel coronavirus pandemic and the economic crash in the United States in 2020 offer an opportunity to explore the impact of economic change on opinions about global warming. Does a sudden decline in the satisfaction of deficiency needs—loss of a job, diminished feelings of safety, reduced economic security—affect American concerns about the natural environment, public support for efforts to protect the environment, and even public belief in the existence of climate change?

In 2018, we collaborated with researchers at Resources for the Future (RFF) and ABC News to conduct a national survey, asking a wide array of questions on the topic of climate change, including questions about its existence, causes, and impacts; who should take action to address it; and more. Some of these same questions were posed again in a new survey we conducted with researchers at RFF and ReconMR, with 999 American adults who were interviewed between May 28, 2020, and August 16, 2020—in the midst of this year’s global pandemic. In May 2020, when the survey went into the field, the national unemployment rate was 13 percent—a level not seen since the Great Depression. During the period the survey was conducted, 19 million Americans filed new claims for unemployment benefits.

Comparing the 2018 and 2020 surveys allows us to assess whether the intervening public health crisis and economic upheaval

- have reduced the number of people who believe in the existence of global warming or the certainty with which people hold those beliefs, perhaps to rationalize reduced support for government action on the issue; and

- have reduced support for government efforts and policies intended to mitigate global warming, in favor of redirecting efforts to focus on the American economy and COVID-19.

This survey provides a glimpse into the collective American psyche during a unique time in the nation’s history. The data from this survey show that, in spite of the array of social, economic, and public health issues affecting the United States today, considerable and sometimes huge majorities of Americans believe that global warming has been happening, will continue in the future, and requires ameliorative action.

Note: When this research program began in 1997, “global warming” was the term in common parlance. That term was used throughout the surveys over the decades and was always defined for respondents, so it was properly understood. In recent years, the term “climate change” has risen in popularity, so both terms are used in this report interchangeably. Empirical studies, such as by Villar and Krosnick (2011), have shown that survey respondents interpret the terms “global warming” and “climate change” to have equivalent meanings.

Do New Crises Take Public Attention Away from a Persistent Existential Threat?

The findings described here complement the work of several contemporary researchers who have studied the relationship between economic well-being and beliefs about global warming.

Maslow’s theory, which suggests that the pursuit of economic well-being competes with advocacy for environmental protection, was the foundation of evidence offered in a 2011 paper in Climate Change Economics by economists Matthew Kahn and Matthew Kotchen. Their paper analyzes the frequency of Google searches between 2004 and 2010 for information about unemployment and information about global warming, on the assumption that searches on a topic reveal the extent of public concern about the topic. They conclude that “recessions increase concerns about unemployment at the expense of people’s interest in climate change—in some cases leading them to deny its existence.”

Kahn and Kotchen also report evidence based on national survey data about the American “Great Recession” collected in 2008 and late 2009 through early 2010. Interestingly, unemployed Americans were no more or less likely than the employed to express belief in the existence of global warming, certainty about that belief, support for an American effort to combat warming, or support for more congressional action on the issue. This evidence refutes the most plausible version of the hierarchy of needs hypothesis: that economic suffering by an individual reduces his or her concern about environmental protection and reduces even the belief in the existence of environmental threats.

However, the researchers did find a correlation between state unemployment levels and residents’ beliefs—respondents living in states with smaller decreases in employment levels tended to believe in global warming more.

But not all evidence is consistent with this reasoning. For example, a 2008 paper by Hanno Sandvik found that, in a comparison of 46 countries, “gross domestic product is … negatively correlated to the proportion of a population that regards global warming as a serious problem.” Thus, better economic conditions predicted less concern about global warming, rather than more concern. Complicating matters further, a 2012 analysis of data from the same surveys in 47 countries by Berit Kvaløy, Henning Finseraas, and Ola Listhaug found that GDP per capita did not predict respondents’ ratings of the seriousness of global warming for the world.

Our 2020 survey has offered the opportunity to test these hypotheses again. The new survey shows that the COVID-19 crisis has not decreased American “green” attitudes or belief in the existence of global warming. At odds with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the findings in this survey offer a new perspective on how global warming fits into individual and national priorities during a time of hardship.

This Year’s Public Health Crisis Has Not Affected the Number of Americans Who Believe in the Existence of Climate Change

Belief in the existence of climate change is approaching the highest observed levels, and people have become increasingly certain of their beliefs about whether Earth has been warming in the past and will warm in the future. In 2020, 81% of Americans believe that Earth has been warming over the last 100 years—among the largest percentages observed since this surveying began in 1997, when the observed level of belief was 77% (Figure 2).

The COVID-19 pandemic, the cratering economy, racial injustice, and so many other pressing societal issues have captured national attention and could have been expected to shift focus away from thinking and learning about climate change. Nevertheless, the fraction of the American public that believes global warming has probably been happening (a broad metric that helps gauge belief in climate change) is both high and stable over time at around 80% over two decades, and at 81% this year. That this percentage is so high is indicative of bipartisan support, as the fraction of Americans who are Republicans is higher than 20%. This is good news for public support for future actions on climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Alan Krupnick, RFF Senior Fellow

Certainty is on the rise, reflecting increasingly entrenched views. Among Americans who do and do not believe that global warming has been happening, the proportion of people who are highly certain of their beliefs about global warming’s existence has increased over the past 23 years.

Among people who believe that global warming has been occurring, the proportion of highly certain individuals was 45% in 1997 and has reached an all-time high of 63% in 2020 (Figure 3).

Among people who do not believe that global warming has been happening over the last 100 years, certainty also has escalated, reaching 44% in 2020. Interestingly, over the past 23 years, three spikes in certainty have arisen among people who are skeptical that Earth has been warming—all following striking declines in average global temperature. These spikes are consistent with the hypothesis that recent changes in average global temperature are important determinants of what we call “existence beliefs” among people who do not trust scientists who study Earth’s climate.

Since 1997, the proportion of Americans who believed that they are knowledgeable about global warming has increased steadily. In 1997, 42% of respondents said they knew at least a moderate amount about the issue, and that figure rose to an all-time high of 75% in 2020.

A record-high number of Americans believe that they know at least a moderate amount about global warming. Interestingly, it appears that increased knowledge has not been accompanied by a similar increase in the number of Americans who believe that climate change is happening. One potential theory is that this increase in perceived knowledge is the result of confirmation bias. As people are increasingly able to seek out information that aligns with their beliefs, climate believers and deniers alike are able to find information that confirms their views. Therefore, people believe they know more about climate change without actually changing their opinions.

Kristin Hayes, RFF Senior Director of Research and Policy Engagement

One indicator of the crystallization of public opinion on an issue—and, consequently, the impact of people’s opinions—is the strength with which people say they hold those opinions. The proportion of people saying their opinions on global warming are extremely or very strong clocks in at 55% in 2020, up from 41% in June 2010 (Figure 4).

For most policy issues, a small group of people known as the “issue public” considers the matter to be of great personal importance. These are the people who pay careful attention to news on the subject, think and talk a lot about it, give money to lobbying groups to influence policy, and vote based on the issue.

In 2020, the global warming issue public constitutes an all-time high of 25% of Americans, up from 9% in 1997 (Figure 5). Thus, a growing proportion of people cares deeply about climate change. That a quarter of Americans comprise the issue public for climate change is particularly important, given that other well-known and controversial issues have attracted lower levels of passion.

This Year’s Public Health Crisis Has Not Reduced Support for Efforts to Mitigate Climate Change

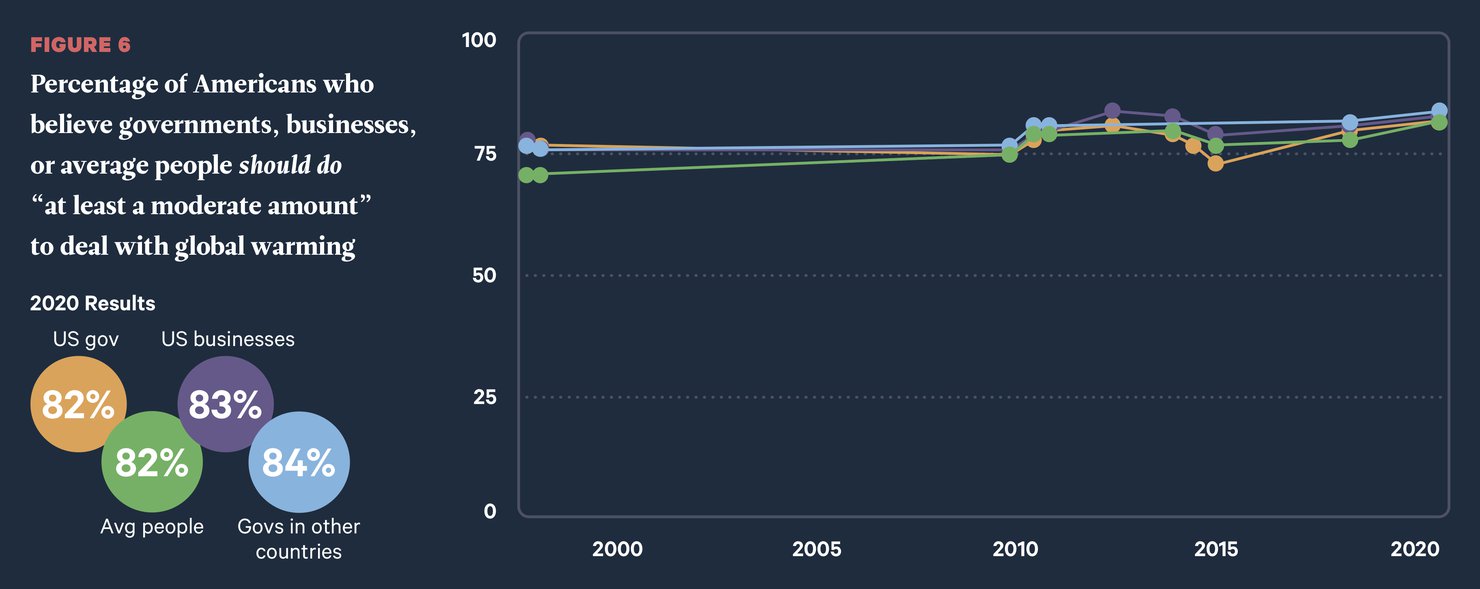

In 2020, 82% of respondents say that the US government should do at least a moderate amount to mitigate global warming—an all-time high for public opinion on the issue (Figure 6). Similar proportions of respondents believe that governments in other countries, businesses, and individuals should do at least a moderate amount to deal with climate change.

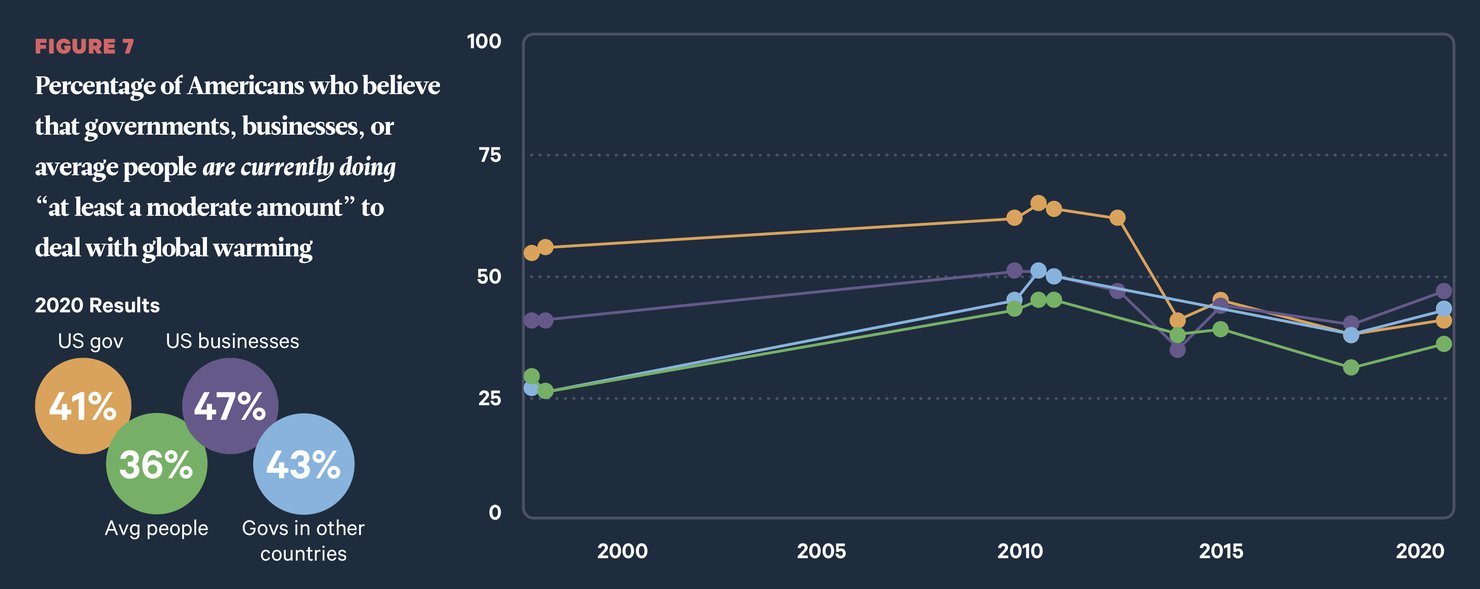

However, most people believe that governments, businesses, and individuals are not doing as much as they should on this issue. Compared to the 80% of people who think governments, businesses, and people should do at least a moderate amount to help mitigate climate change (Figure 6), far fewer believe that these groups are actually taking much action—only 35% to 45% of people think these groups currently are doing at least a moderate amount to deal with climate change (Figure 7).

Most people want more action on climate change from each of the four groups mentioned. The proportion of people who believe that the US government, governments in other countries, businesses, or average people should do more to deal with climate change is about 70% in all categories. This desire for increased effort remains about what it was in 1997.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created an unprecedented global scenario for energy use and emissions. The last six months have shown us a dramatic example of how sudden action by multiple stakeholders can significantly impact emissions. As RFF’s Global Energy Outlook report explains, energy demand contracted sharply as businesses shuttered and people traveled less with the onset of COVID-19. Some projections estimate that emissions could fall by roughly 8 percent this year, returning to 2010 levels. However, absent changes in public policies to address climate change, a return to economic growth likely means a return to emissions growth. Projections suggest that the world may be on the cusp of its first true energy transition, but more ambitious government policies and technological innovations are needed to satisfy the energy demands of a growing world while also achieving long-term environmental goals.

Richard Newell, RFF President and CEO

Consistent Attitudes, Despite Unexpected Crises

The results of this survey illustrate that, despite numerous efforts over the past two decades to change public opinion, Americans’ views on climate change have been remarkably consistent. For numerous important issues in American politics, public opinion has changed extraordinarily slowly through the decades—if at all. As we see here, attitudes toward climate change have a similar inertia.

As in 1997, the 2020 survey results show considerable and sometimes huge majorities expressing what might be called “green” views on climate change and related issues. These high levels of agreement are not often seen in American politics these days, and the coherent response identifies an arena that crosses party lines. This is the sort of public opinion that policymakers hope for, so they can move forward by creating policies that carry the support of a large swath of their constituents. But although the majority of Americans believe that something should be done about climate change—whether by the federal government, world leaders, businesses, or individuals—the details of how something should be done remains a point of contention among legislators.

Even with so much evidence of continuity over time, we see signs of change in this survey. In particular, we see Americans believing they know more about this issue and are more certain of their opinions than in the past.

Taken together, this evidence appears to refute the theory that concern about climate change is a luxury good that the public cannot afford in times of crisis. This sort of evidence helps scholars of public opinion to better understand the American public—and for Americans to better understand themselves.

This article is based on “Climate Insights 2020: Surveying American Public Opinion on Climate Change and the Environment,” a report published by Resources for the Future in August 2020.