Recently, Rep. Doug Ose (R-CA) proposed legislation (the "Department of Environmental Protection Act") that would elevate the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to a cabinet department and create within it a Bureau of Environmental Statistics (or BES). While cabinet status for EPA may have symbolic or organizational advantages, the creation of a BES could prove to be the most meaningful portion of the bill—and an important development for future environmental policymaking.

The Ose bill would authorize the proposed BES to collect, compile, analyze, and publish "a comprehensive set of environmental quality and related public health, economic, and statistical data for determining environmental quality...including assessing ambient conditions and trends."

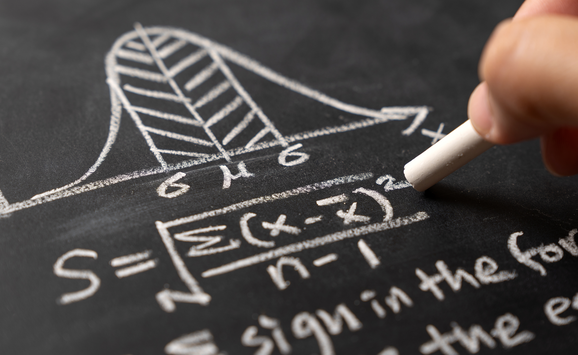

Why do we need another bureaucratic agency collecting statistics? The overarching reason is that we simply do not have an adequate understanding of the state of our environment. In many cases, the network of monitors measuring environmental quality is insufficient in geographic scope. For example, in many cases our knowledge of national air quality is based on a few monitors per state; our knowledge of water quality is even weaker. The measures we do have typically focus on potential problem areas—a sensible approach from the standpoint of enforcement, but not for surveying the overall state of things. Accordingly, we must make inferences about overall quality from observations at these trouble spots. The consequence is a biased understanding of environmental quality.

Of course, this easy answer begs the further question of why we need a better understanding of the state of our environment. There are several good reasons.

First, we have a natural desire to understand broad trends that affect our society and its welfare. Indeed, it is for this reason that we first began to collect many of our national economic statistics, including the familiar measures of gross domestic product (GDP) and inflation. Yet from the origins of GDP accounting, in A.C. Pigou's seminal Wealth and Welfare (1912), it was acknowledged that GDP is only a proxy and not a perfect measure of welfare because it omits many important components that do not pass through markets. Even then, the environment was acknowledged to be one of the important omissions. Since that time, we have invested enormous resources in improving measures of the market components of national well-being, but we have not proportionately broadened that effort to other components, like the environment. It is time to do so.

But the knowledge gap about our environment is more significant than a mere shortage of beans for bean counters. It manifests itself in every stage of policy design and evaluation.

Second, our ability to design effective policies to balance environmental quality with other objectives, or to attain environmental objectives in the most efficient and effective manner, is hampered by inadequate information. As professional social scientists, we at RFF would probably always want more data to analyze. But the knowledge gap is more significant than a mere shortage of beans for bean counters. It manifests itself in every stage of policy design and evaluation.

Looking in the rearview mirror, in many cases we do not know whether existing policies have been effective, making it difficult to assess what remains to be done. Looking forward, we often find that the playbook of strategies with which one might attack environmental problems is limited by lack of information. Sometimes, the lack of information creates practical problems for implementing and enforcing a strategy. For example, it is difficult to imagine a serious effort to manage the total maximum daily load of pollutants into our nation's watersheds, as EPA has proposed, without more complete data about pollution loadings and their sources. At other times, the lack of information makes it difficult to anticipate the effects of a policy, creating political uncertainties. For example, the cap-and-trade system, proven to be a highly cost-effective way to reduce air pollution nationally, may allow remaining pollution to concentrate in particular areas. Without a more thorough monitoring network, it is impossible to know whether these so-called hot spots are a serious problem. The consequence is hesitation in further use of this potentially effective policy instrument.

A third reason we should want better environmental statistics is that many expensive environmental regulations, with serious consequences for businesses and local economies, are triggered by incomplete information. A prominent example is compliance with air quality standards. Counties and regions that fail to meet these standards risk loss of federal highway dollars, bans on industrial expansion, and mandatory installation of expensive pollution-abatement equipment. Compliance is often based on readings from a small number of monitors. A fair question is whether some communities have been singled out while others have escaped detection. Moreover, although readings from only one monitor may push a portion of a county over a pollution threshold, reestablishing a clean slate once air quality has improved is much more difficult. Recent research by Michael Greenstone of the University of Chicago has shown that many counties remain in official noncompliance even though readings from the available monitors have shown compliance for many years. The Catch-22 is that a county must prove compliance throughout its jurisdiction even if the monitoring network is inadequate to shed light on all areas.

Creating a BES would also facilitate "one-source shopping" for members of Congress, agency administrators, and the public, who currently must navigate a maze of agencies to construct a picture of the nation's environment. In addition, an independent BES might lend more credibility—a sense of objectivity—to our environmental statistics, giving the public a commonly accepted set of facts from which to debate policy, much as the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis have done for economic statistics.

Although environmental statistics will probably never hit people’s pocketbooks as directly as did the CPI, they can get caught in the crossfire between business and environmental groups.

Lessons Learned from the CPI

Indeed, our experience with economic statistics teaches us a number of lessons for a BES. First, statistics can be politically controversial. Although widely accepted now, some economic statistics were the focus of past controversy. During World War II, for example, industrial wages were linked to changes in the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI). At the same time, the CPI began to move out of synch with the popular perception of price changes, recording much lower inflation rates than people experienced in their everyday lives, largely because it missed quality deterioration in the goods selling at modestly increasing prices: eggs were smaller, housing rental payments no longer included maintenance, tires wore out sooner, and so forth. The result was political uproar, with protests on the home front from organized labor. In the end, a lengthy review process, with representatives from labor, industry, government, and academic economists, resolved the issue.

Although environmental statistics will probably never hit people's pocketbooks as directly as did the CPI, they can get caught in the crossfire between business and environmental groups. Building in a regular external review process would help keep the peace during such moments. Crises aside, external reviews would ensure that a BES is balanced and objective, in both fact and perception, and help improve its quality over time.

Indeed, the regular external reviews of the CPI have raised points that would be of value to a future BES. Some are academic questions about sampling and analyzing data and could be addressed within the agency. Others may require congressional action from the beginning, such as the need for data sharing. In our economic statistics, there is substantial overlap between information collected for the U.S. Census (housed within the Department of Commerce), unemployment statistics and the CPI (collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics), and the GDP (collected by the Bureau of Economic Analysis). To address this concern, Congress recently passed the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act, which allows the three agencies to share data and even coordinate their data collection.

Similar data-sharing issues would arise for environmental statistics. Currently, environmental statistics are collected not only by EPA but also by the Departments of Agriculture, Interior, Energy, and Defense. Even some of the economic statistics collected by the Census Bureau and other agencies would overlap in a complete picture of environmental statistics. Coordination across these agencies—and in some cases consolidating tasks into the new agency—would be essential for producing the best product without duplication of effort.

Coordination across these agencies—and in some cases consolidating tasks into the new agency—would be essential for producing the best product without duplication of effort.

An additional insight gained from looking back on our experience is that economic statistics now play a much larger role in our economy and in economic planning than originally envisioned. Most generally, they have been used as a scorecard for the nation's well-being, a basis for leaders to set broad policy priorities (stop inflation, spur growth), and a basis for the public to assess its leaders. At a more detailed level, they now fit routinely into the Federal Reserve's fine-tuning of the economy. Finally, through indexing of wages and pensions, tax brackets, and so on, the CPI automatically adjusts many of the levers in the economic machine.

One could imagine environmental statistics playing each of these roles. First, despite their current weaknesses, environmental statistics already help us keep score of our domestic welfare. Second, they increasingly could be used to adjust policies. Initially, environmental statistics may serve as early warning signals for problems approaching on the horizon (or all-clear signals for problems overcome). Later, as the data develop and policies evolve to take advantage of them, they may even be used in fine-tuning. For example, on theoretical drawing boards, economists have already designed mechanisms that, based on regularly collected data, would dynamically adjust caps for pollution levels or annual fish catches. The only thing missing is the data with which to make such mechanisms possible.

A final lesson learned is that high-quality statistics cannot be collected on the cheap. We currently spend a combined $722 million annually on data collection for the U.S. Census (excluding special expenditures for the decennial census), the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and more than $4 billion each year for statistical collection and analysis throughout the federal agencies. Over the past three years, these budgets have increased at annual rates of approximately 6.5% and 9.7%, respectively. Nevertheless, these efforts are widely considered to be well worth the cost.

By comparison, the current budget of $168 million for environmental statistics seems small. Consider that in 1987—the last year for which comprehensive data are available!—the annual private cost of pollution control was estimated to be $135 billion, and that government spends $500 million a year for environmental enforcement. With approximately 2% of our GDP at stake in these expenditures, and the welfare of many people, a top-notch set of environmental statistics seems long overdue.

Spencer Banzhaf is an RFF fellow. His research centers on nonmarket valuation of air quality and other public goods. His recent work proposes an approach to incorporating public goods into cost-of-living indexes, such as the U.S. Consumer Price Index.

For More Information

- Greenstone, Michael. 2003. "Did the Clean Air Act Amendments Cause the Remarkable Decline in Sulfur Dioxide Concentrations?" Working paper, University of Chicago, Department of Economics.

- Pigou, A.C. 1912. Wealth and Welfare. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Costs of the statistical programs of the federal government are tracked by the Office of Management and Budget. See Statistical Programs of the United States Government (www.fedstats.gov/policy).

- Pollution abatement costs were reported in U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Investments: The Cost of a Clean Environment, EPA-230-11-90-083, Nov. 1990. More recent, but less comprehensive statistics are collected by the U.S. Census Bureau; see Pollution Abatement Costs and Expenditures: 1999, Nov. 2002 (available at www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/ma200-99.pdf).